By cleverly unraveling the workings of a natural cosmic lens, astronomers have gained a rare glimpse of the violent assembly of a young galaxy in the early universe. Their new picture suggests that the galaxy has collided with another, feeding a super-massive black hole and triggering a tremendous burst of star formation.

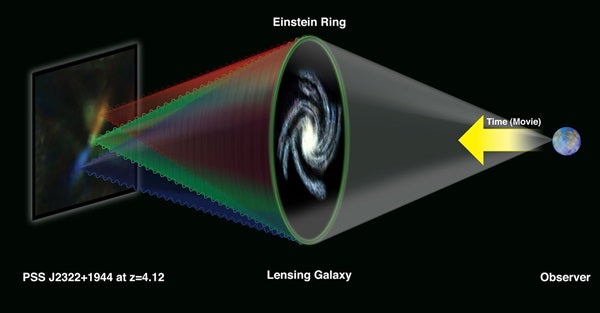

The astronomers used the National Science Foundation’s Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope in Socorro, New Mexico, to look at a galaxy more than 12 billion light-years from Earth, seen as it was when the universe was only about 15 percent of its current age. Between this galaxy and Earth, lies another distant galaxy so perfectly aligned along the line of sight that its gravity bends the light and radio waves from the farther object into a circle, or “Einstein Ring.”

This gravitational lens made it possible for the scientists to learn details of the young, distant galaxy that would have been unobtainable otherwise.

“Nature provided us with a magnifying glass to peer into the workings of a nascent galaxy, providing an exciting look at the violent, messy process of building galaxies in the early history of the universe,” said Dominik Riechers, who led this project at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany and now is a Hubble Fellow at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena.

The new picture of the distant galaxy, dubbed PSS J2322+1944, shows a massive reservoir of gas, 16,000 light-years in diameter, that contains the raw material for building new stars. A super-massive black hole is voraciously eating material, and new stars are being born at the rate of nearly 700 suns per year. By comparison, our Milky Way Galaxy produces the equivalent of about three to four suns per year.

The black hole appears to be near the edge, rather than at the center, of the giant gas reservoir. Astronomers say this location indicates the galaxy has merged with another.

“This whole picture of massive galaxies and super-massive black holes assembling themselves through major galaxy mergers so early in the universe is a new paradigm in galaxy formation. This gravitationally lensed system allows us to see this process in unprecedented detail,” Chris Carilli of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory in Charlottesville, Virginia, said.

In 2003, astronomers studied PSS J2322+1944 and found the Einstein Ring by observing carbon monoxide (CO) molecules emit radio waves. When astronomers see large amounts of CO in a galaxy, they conclude that there also is a large amount of molecular hydrogen present, and thus a large reservoir of fuel for star formation.

In the latest study, scientists painstakingly produced a physical model of the lensing intermediate galaxy. By knowing the galaxy’s mass, structure, and orientation, they deduced the details of how it bends light and radio waves from the more-distant galaxy. Then they reconstructed a picture of the distant object. By doing multiple VLA images made at different radio frequencies helped the team measure the motions of the gas in the distant galaxy.

“The lensing galaxy was, in effect, part of our telescope. By projecting backward through the lens, we determined the structure and dynamics of the galaxy behind it,” Fabian Walter said of the Max-Planck Institute for Astronomy in Germany.

George Djorgovski of Caltech used the digitized Palomar Observatory Sky Survey to discover PSS J2322+1944. Later radio and optical studies showed it had a huge reservoir of dust and molecular gas and indicated gravitational lensing.

Albert Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity predicted gravitational lenses in 1919. In 1936, Einstein showed that a perfectly aligned gravitational lens would produce a circular image, but he felt the chances of actually observing such an object were nearly zero. The first gravitational lens was discovered in 1979, and researchers using the VLA in 1987 discovered the first Einstein Ring.