An international group of researchers found a new technique that establishes the intrinsic brightness of Type Ia supernovae more accurately than ever before. These exploding stars are the best standard candles for measuring cosmic distances, the tools that made the discovery of dark energy possible. The group — the Nearby Supernova Factory (SNfactory) — is a collaboration among the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, a consortium of French laboratories, and Yale University.

Stephen Bailey from the Laboratory of Nuclear and High-Energy Physics (LPNHE) in Paris searched the spectra of 58 Type Ia supernovae in the SNfactory’s dataset and found a key spectroscopic ratio. A supernova’s distance can be determined to better than 6 percent uncertainty simply by measuring the ratio of the flux (visible power, or brightness) between two specific regions in the spectrum of a Type Ia supernova taken on a single night.

The new brightness-ratio correction appears to hold no matter what the supernova’s age or metallicity (mix of elements), its type of host galaxy, or how much it has been dimmed by intervening dust.

Using classic methods that are based on a supernova’s color and the shape of its light curve — the time it takes to reach maximum brightness and then fade away — the distance to Type Ia supernovae can be measured with a typical uncertainty of 8 to 10 percent. But obtaining a light curve takes up to 2 months of high-precision observations. The new method provides better correction with a single night’s full spectrum that can be scheduled based on a much less precise light curve.

An invaluable collection of light

Bailey said that the SNfactory’s library of high-quality spectra is what made his successful results possible. “Every supernova image the SNfactory takes is a full spectrum,” he said. “Our dataset is by far the world’s largest collection of excellent Type Ia time series, totaling some 2,500 spectra.”

The most accurate standardization factor Bailey found was the ratio between the 642-nanometer wavelength, in the red-orange part of the spectrum, and the 443-nanometer wavelength, in the blue-purple part of the spectrum. In his analysis, he made no assumptions about the possible physical significance of the spectral features. Nevertheless he turned up multiple brightness ratios that were able to improve standardization over current methods applied to the same supernovae.

“This is an example of exactly what we designed the Nearby Supernova Factory to do,” said Greg Aldering of Berkeley Lab’s Physics Division. “Stephen’s agnostic approach — ‘I don’t know what these ratios are, but maybe I can use them for standardization’ — underlines the vital role of detailed spectrometry in discoveries of cosmic significance.”

“While the luminosity of a Type Ia supernova indeed depends on its physical features, it also depends on intervening dust,” said Rollin Thomas of Berkeley Lab’s Computational Research Division. “The 642/443 ratio somehow aligns those two factors, and it’s not the only ratio that does. It’s as if the supernovae were telling us how to measure it.”

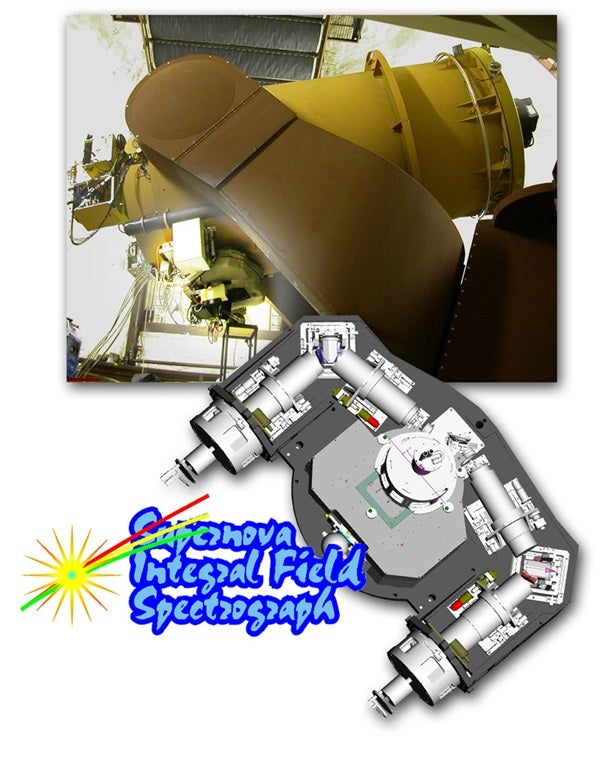

The SNfactory first finds candidate Type Ia supernovae using a wide-field CCD camera developed and operated by its collaborators at Yale University, then makes spectral images of promising candidates with the University of Hawaii’s 2.2-meter telescope on Mauna Kea. The telescope is equipped with the SuperNova Integral Field Spectrograph (SNIFS).

“Type Ia spectrometry is mostly done to find out whether or not a supernova actually is a Type Ia,” said Aldering. “Often it’s with a slit spectrometer that loses a lot of light in some wavelengths or with filtered photometry that selects for certain colors. With SNIFS, we get all the light. Stephen’s analysis was done with brightnesses he knew were correct at all wavelengths.”

Because the dataset was large enough, the search for the crucial wavelength ratios could be done using statistical procedures not always available to a field that, in Thomas’ words, “is often data-starved.” The SNfactory researchers were able to select 58 supernovae whose redshifts were not corrupted by the random motion of their parent galaxies, all of them within two and a half days of their maximum brightness in their own neighborhoods.

To eliminate bias, the search for the ratios that best correlated with absolute magnitudes (standardized brightnesses) began with a “training” set of 28 of the supernovae in the sample said Bailey. The five best ratios from the training sample were then applied to the remaining 30 supernovae in the “validation” sample. The correlation between both sets was consistent and very strong.

“Astronomers have looked for spectral features that could be used to correct observed magnitudes before,” said Bailey, “but their searches tended to concentrate on a known physical feature, for example a silicon or sulfur line. In high-energy physics, we’re often dealing with huge datasets and looking for whatever we can find. I decided not to make any physical assumptions about the SNfactory dataset but just see what the spectra could tell me by themselves.”

The tip of the cosmic iceberg

“These are the first general cosmology results from the large, full-spectrum sample obtained by SNIFS, but they are only the tip of the iceberg,” said Yannick Copin of the Institute of Nuclear Physics of Lyon, France (IPNL). It shows we can do much more in cosmology with spectral time series than we could ever do before. A universe of possibilities is open before us.”

Dark energy was discovered by creating a Hubble diagram, a graph comparing the distance and redshift of a few dozen Type Ia supernovae. Using their new brightness-ratio correction, SNfactory researchers have fit standardized supernovae to a Hubble diagram with far less uncertainty than the classic method. The new Hubble diagrams from the SNfactory have the lowest scatter of data points ever published for such a large and diverse sample.

Says Aldering, “Right now the main questions in using Type Ia supernovae to study the expansion of the universe are basic cosmology — anchoring the Hubble diagram — and reducing systematic errors — the physics of supernovae, and understanding the role of intervening dust. The new brightness-ratio correction will be a major tool for anchoring the Hubble diagram. In turn, that really narrows what remains to be explained about the systematics.”

“Our longstanding goal has been to make use of all the information a supernova gives us about its physical condition as it brightens and fades away, and we get to see deeper and deeper into its atmosphere,” said Saul Permutter, cofounder of the SNfactory. “Finally we’ve built a dataset with the size and quality to allow us to do this. These spectra open the possibility of many kinds of new measurements from the ground and in space.”

For studying dark energy, there’s another challenge and that’s obtaining enough high-quality full spectra of distant Type Ia supernovae — a set comparable to the “nearby” supernovae in the SNfactory’s dataset. Future space missions or ground-based missions will need spectrometry as good as that provided by the SNfactory’s SNIFS spectrograph to reduce systematic errors hand in hand with the improvement in statistics — and to find what’s in the cosmos that our assumptions may have hidden.