Key Takeaways:

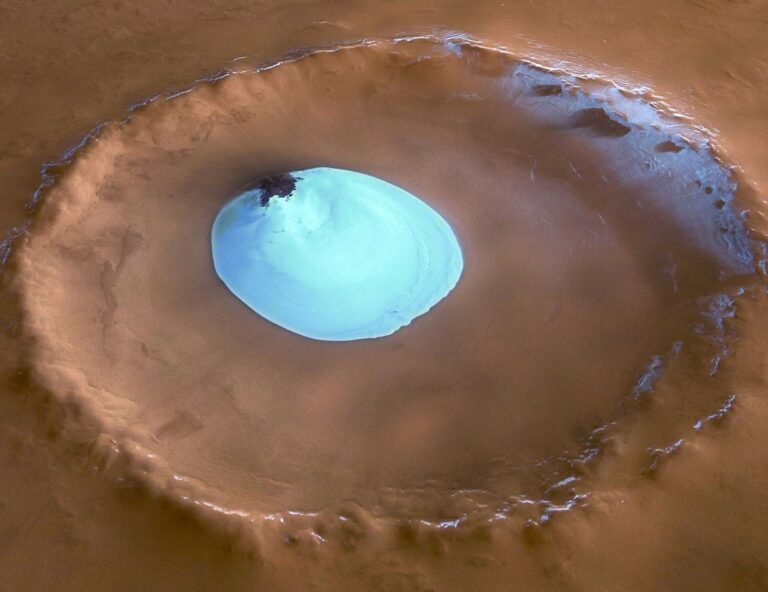

We’ve always known Mars as the Red Planet — but it turns out, we may have had the reason why wrong. If so, it could revise much of what we know about the history of our smaller neighbor planet.

In a study published Feb. 25 in Nature Communications, researchers tied the nature of Mars’ red tint to a particular species of iron mineral. While it’s never been in doubt that Mars’ red was a consequence of iron and water interacting, exactly how and when it happened has proven more elusive.

All about the iron

The new study points to ferrihydrite as the culprit for Mars’ color. This is basically water-rich iron. So, the researchers think the planet was first covered in water for a decent amount of time, then clung to the iron-rich soil over a long period while the planet dried up. The study also shows that the environment of early Mars may have been colder than we thought.

“The presence of ferrihydrite tells us something specific about Mars’ past environment,” says Adomas Valantinas, a postdoctoral fellow at Brown University and lead author on the paper. According to Valantinas, the mineral typically forms in cool conditions where the environment has roughly neutral pH and conditions are ripe for oxidation — a certain type of chemical reaction that, in the case of iron, forms rust. Essentially, “this suggests that rather than warm conditions, early Mars experienced a cold and wet environment,” Valantinas says.

Previous models supported an environment of dry oxidation of iron in hematite form. That is, assuming exposure to atmospheric oxygen created the red hue. Iron in a ferrihydrite form suggests the need for water over a longer period of time in order to create that rich, orange-red hue.

Gathering data

Data from several missions were used to detect ferrihydrite, including ESA’s Trace Gas Orbiter, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and several rovers. Various iron oxides (iron that has been exposed to oxygen) give off different wavelengths of light. By combining data across these missions, Valantinas and his colleagues were able to find that ferrihydrite is the predominate species of iron on the martian surface.

The data also indicate that ferrihydrite may have come to dominate the martian surface about 3 billion years ago. Valantinas says that during this time, intense volcanic activity on Mars was likely triggering melting of ices on the surface. This period, called the Hesperian period, is known for its intense floods as well, and marked the turning point in the planet’s history where the surface water began to disappear.

“The timing aligns with a period when Mars was transitioning from its earlier, wetter state to its current desert environment,” Valantinas says.

Much to learn

There isn’t much doubt that Mars was once covered in bodies of water. But it’s the other factors we are still putting together — how deep the seas were, how long they lasted, how widespread they were, and more. This study tells us that Mars may not have been such a balmy place, and during the Hesperian period was rather cold. Understanding the conditions in which the ferrihydrite formed will help piece together the process by which the water evaporated. And the loss of Mars’ oceans is tied to the loss of its atmosphere as well, as both may have been due to the same processes.

Valantinas says the Mars Sample Return mission could provide the crucial evidence needed to figure out the role of ferrihydrite in the color of Mars, as well as exactly how it formed. It could even tell us about Mars as a place that potentially once held life as well, if it ever arose.

“If ferrihydrite is confirmed in the returned martian samples, stable isotope measurements of iron, hydrogen, and oxygen would be of particular interest,” he says. Isotopes are simply particular “flavors” of elements, containing the same number of protons in their nucleus but different numbers of neutrons. “These measurements could reveal the water temperature in which ferrihydrite formed, the water’s source (whether meteoritic or marine), and potentially even whether microbes played a role in ferrihydrite formation.”