A nearby star that may host a planet or two could provide a clue about whether planets orbiting the smallest stars can survive the bullying of their suns.

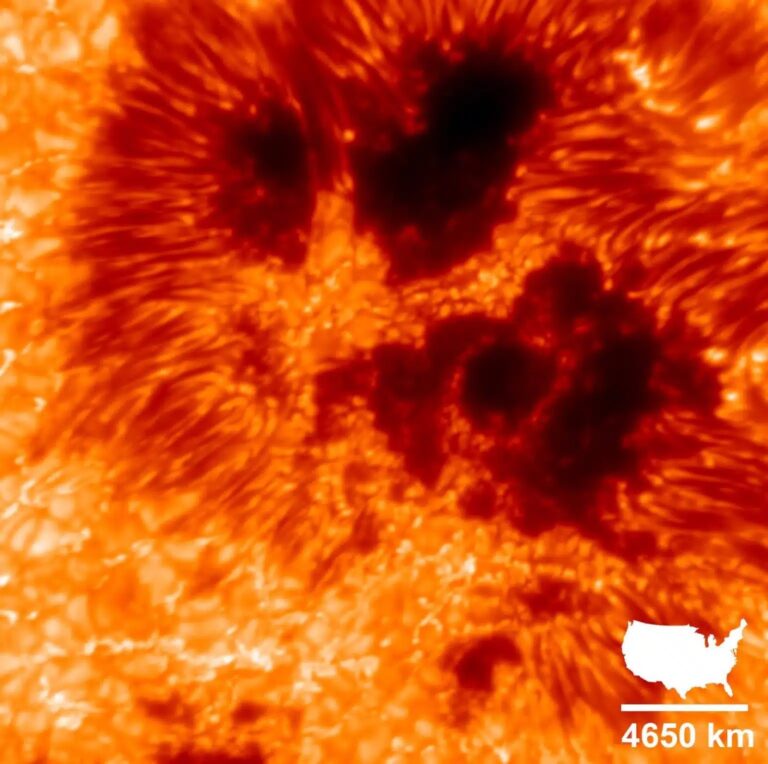

In a press conference last week at the 245th meeting of the American Astronomical Society, Scott Wolk of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory presented his findings on Wolf 359, a red dwarf star about 8 light-years away. The star is small, only about 11 percent the mass of the Sun, but its flares pack a wallop.

Wolk observed the system in X-rays to see whether any planets it might host could survive with their atmospheres intact, despite the radiation from their host star. (While some observations have suggested Wolf 359 hosts a planetary system, its existence hasn’t been confirmed.)

Under attack

“The star is very, very X-ray bright, and that can be very bad for exoplanets which we would hope to host habitable life,” Wolk says. “But there’s hope.”

X-rays are some of the most energetic radiation produced by stars. That makes them particularly deadly to would-be life. And red dwarf stars like Wolf 359 are known to produce a lot of radiation — often in the form of flares and other lash-outs. Because of the small size of such stars, planets around them would have to be in very close orbits to sustain life. But that’s also directly in the path of a lot of the radiation. This suggests that, especially in the first few billion years of their lives when stars are most active, any planets’ nascent atmospheres probably get stripped away and hopes for life are dashed.

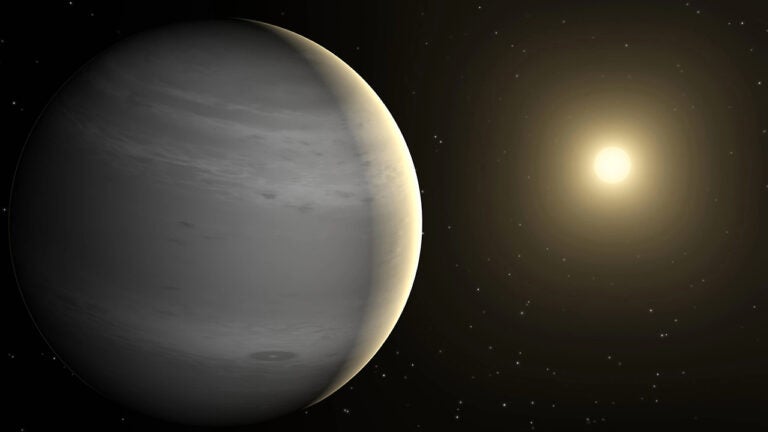

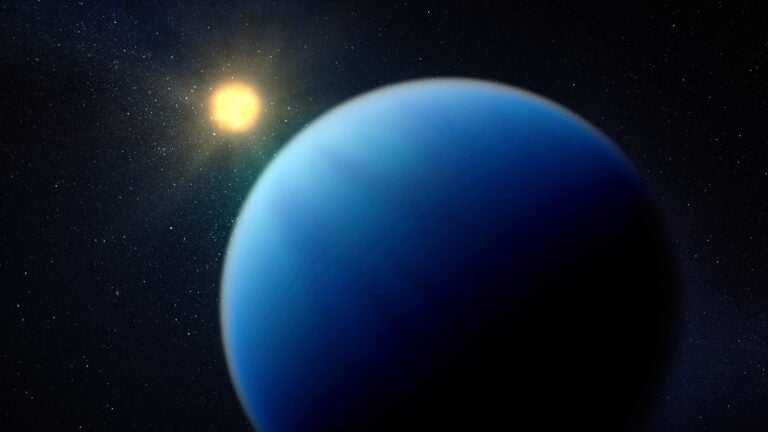

Wolk looked at data from the XMM-Newton mission to investigate the conditions for two planetary candidates at Wolf 359 — one at the inner edge of the habitable zone (approaching too hot, but not hopeless) and one at the outer edge (same thing, but cold). The habitable zone is the region around a star where a planet with an atmosphere could retain liquid water on its surface. Wolk modeled atmospheric conditions similar to those of planets in our solar system, including an Earth-like atmosphere, a Venus-like atmosphere, and either of these with an ocean.

The right conditions

The potential planet at the inner edge of the habitable zone was toast. But the outer one was interesting. An Earth-like atmosphere here would be gone within 2 million years. A Venus-like atmosphere would vanish within 200 million years. That bodes poorly for the existence of long-term life on exoplanets orbiting red dwarfs, which also happen to be the most plentiful type of star.

But if that planet hosted a huge ocean — something like eight times the volume of ours on Earth — and a Venus-like atmosphere, things could be different. A planet like this could exist for 4 billion years with an intact atmosphere — pretty good chances for hosting life.

“If you are lucky, yes, an exoplanet like this could support life,” Wolk says. And while he adds that it seems like those odds are quite long, it’s important to keep in mind that red dwarfs like Wolf 359 are the most numerous type of star. “There are lots of M stars [red dwarfs], so there are lots of exoplanets. And so these are the cases we can be looking for,” he says.

Currently, our best tool for finding habitable exoplanets is the James Webb Space Telescope. And it is ideal for examining stars like Wolf 359 and TRAPPIST-1, which hosts seven confirmed exoplanets, all roughly Earth-sied. The search there thus far has failed to detect any atmospheres, but astronomers remain undaunted. Because if Wolk’s study shows nothing else, it’s that the search isn’t hopeless.