The same object that dazzled skygazers in 1054 continues to dazzle astronomers today by pumping out radiation at higher energies than anyone expected. Researchers have detected pulses of gamma rays with energies exceeding 100 billion electron volts (100 GeV) — a million times more energetic than medical X-rays and 100 billion times more than visible light.

“If you asked theorists a year ago whether we would see gamma-ray pulses this energetic, almost all of them would have said, ‘No.’ There’s just no theory that can account for what we’ve found,” said Martin Schroedter of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

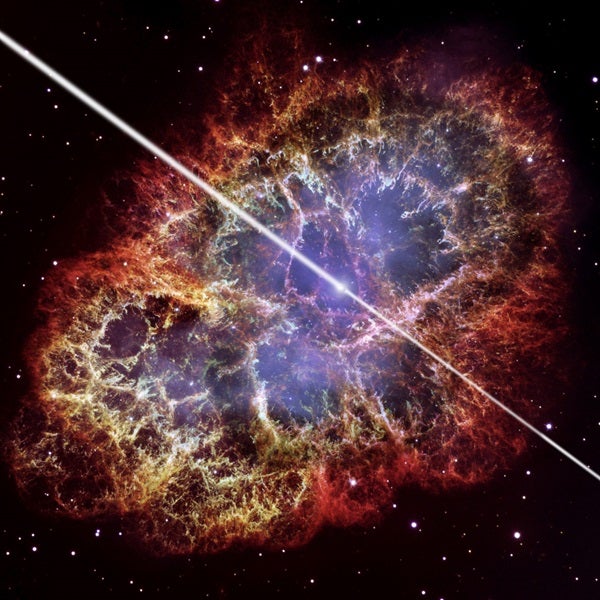

The gamma rays come from an extreme object at the Crab Nebula’s center known as a pulsar. A pulsar is a spinning neutron star — the collapsed core of a massive star. Although only a few miles across, a neutron star is so dense that it weighs more than the Sun.

Rotating about 30 times a second, the Crab pulsar generates beams of radiation from its spinning magnetic field. The beams sweep around like a lighthouse beacon because they’re not aligned with the star’s rotation axis. So although the beams are steady, they’re detected on Earth as rapid pulses of radiation.

An international team of scientists reported the discovery. Nepomuk Otte from the University of California, Santa Cruz, said that some researchers had told him he was crazy to even look for pulsar emission in this energy realm.

“It turns out that being persistent and stubborn helps,” Otte said. “These results put new constraints on the mechanism for how the gamma-ray emission is generated.”

Some possible scenarios to explain the data have been put forward, but it will take more data, or even a next-generation observatory, to really understand the mechanisms behind these gamma-ray pulses.

The Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System (VERITAS) — the most powerful high-energy gamma-ray observatory in the Northern Hemisphere — detected the gamma-ray pulses. VERITAS is located at the Smithsonian’s Whipple Observatory, just south of Tucson, Arizona.

Astronomers observe very-high-energy gamma rays with ground-based Cherenkov telescopes. These gamma rays, coming from cosmic “particle accelerators,” are absorbed in Earth’s atmosphere, where they create a short-lived shower of subatomic particles. The Cherenkov telescopes detect the faint, extremely short flashes of blue light that these particles emit (named Cherenkov light) using extremely sensitive cameras. The images can be used to infer the arrival direction and initial energy of the gamma rays.

This technique is used by gamma-ray observatories throughout the world, and was pioneered under the direction of CfA’s Trevor Weekes using the 10-meter Cherenkov telescope at Whipple Observatory. The Whipple 10-meter telescope was used to detect the first galactic and extragalactic sources of very-high-energy gamma rays.

The same object that dazzled skygazers in 1054 continues to dazzle astronomers today by pumping out radiation at higher energies than anyone expected. Researchers have detected pulses of gamma rays with energies exceeding 100 billion electron volts (100 GeV) — a million times more energetic than medical X-rays and 100 billion times more than visible light.

“If you asked theorists a year ago whether we would see gamma-ray pulses this energetic, almost all of them would have said, ‘No.’ There’s just no theory that can account for what we’ve found,” said Martin Schroedter of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The gamma rays come from an extreme object at the Crab Nebula’s center known as a pulsar. A pulsar is a spinning neutron star — the collapsed core of a massive star. Although only a few miles across, a neutron star is so dense that it weighs more than the Sun.

Rotating about 30 times a second, the Crab pulsar generates beams of radiation from its spinning magnetic field. The beams sweep around like a lighthouse beacon because they’re not aligned with the star’s rotation axis. So although the beams are steady, they’re detected on Earth as rapid pulses of radiation.

An international team of scientists reported the discovery. Nepomuk Otte from the University of California, Santa Cruz, said that some researchers had told him he was crazy to even look for pulsar emission in this energy realm.

“It turns out that being persistent and stubborn helps,” Otte said. “These results put new constraints on the mechanism for how the gamma-ray emission is generated.”

Some possible scenarios to explain the data have been put forward, but it will take more data, or even a next-generation observatory, to really understand the mechanisms behind these gamma-ray pulses.

The Very Energetic Radiation Imaging Telescope Array System (VERITAS) — the most powerful high-energy gamma-ray observatory in the Northern Hemisphere — detected the gamma-ray pulses. VERITAS is located at the Smithsonian’s Whipple Observatory, just south of Tucson, Arizona.

Astronomers observe very-high-energy gamma rays with ground-based Cherenkov telescopes. These gamma rays, coming from cosmic “particle accelerators,” are absorbed in Earth’s atmosphere, where they create a short-lived shower of subatomic particles. The Cherenkov telescopes detect the faint, extremely short flashes of blue light that these particles emit (named Cherenkov light) using extremely sensitive cameras. The images can be used to infer the arrival direction and initial energy of the gamma rays.

This technique is used by gamma-ray observatories throughout the world, and was pioneered under the direction of CfA’s Trevor Weekes using the 10-meter Cherenkov telescope at Whipple Observatory. The Whipple 10-meter telescope was used to detect the first galactic and extragalactic sources of very-high-energy gamma rays.