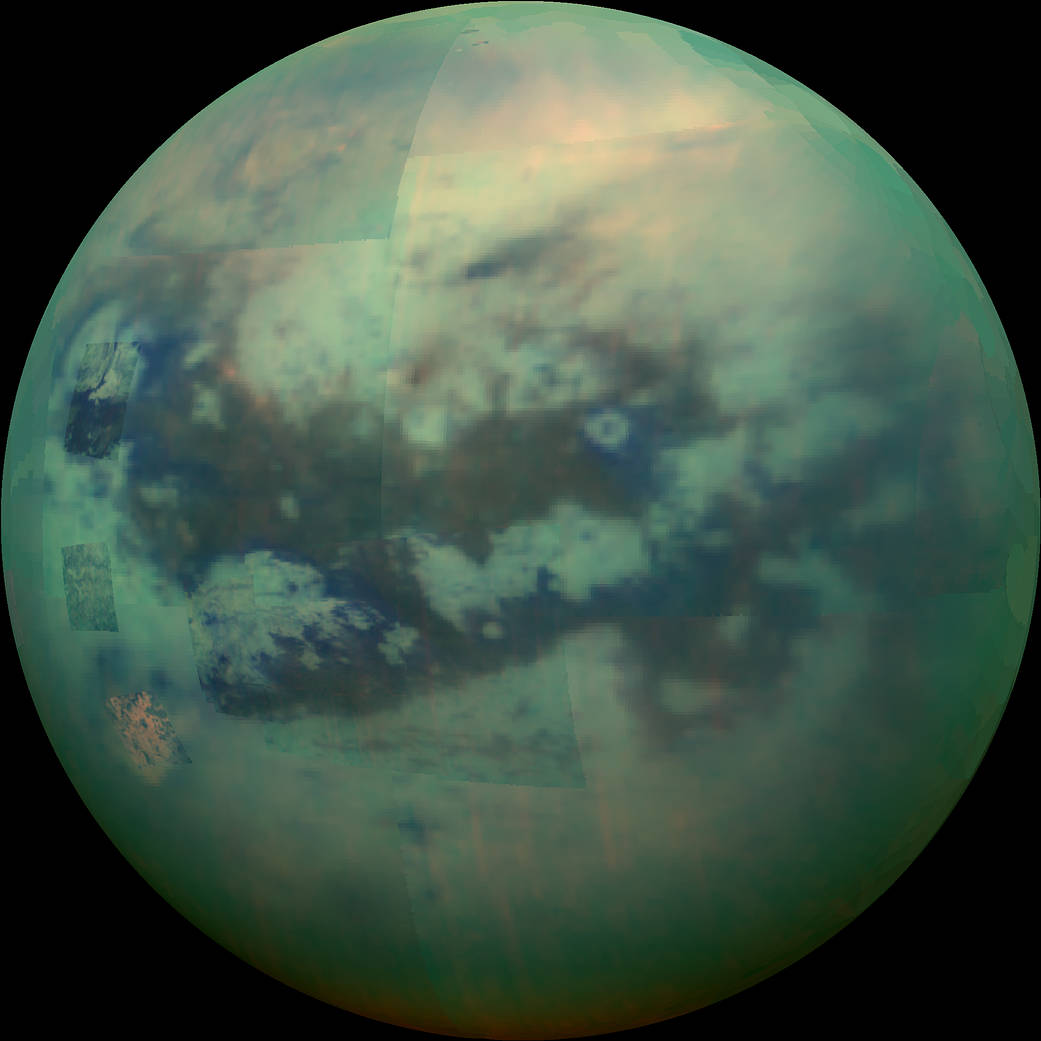

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, is particularly captivating for scientists. This is thanks in large part to its status as the only other planetary body in the solar system known to host an atmosphere about 1.5 times denser than Earth’s and bodies of liquid on its surface. (Unlike Earth, however, where most surface liquid is water, Titan is so frigid — about –290 degrees Fahrenheit [–179 degrees Celsius] — that the liquid present there is made up of hydrocarbons like methane and ethane.)

But even such a large moon lacks the mass to keep a tight hold on its atmosphere. Now, new experimental research published Feb. 1 in Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta shows that the chemical compounds in Titan’s atmosphere could emerge from processes in its interior, offering a way to replenish the moon’s thick atmosphere.

Mysterious Titan

When NASA sent the Voyagerprobes on a grand tour of the outer solar system, it elected to send Voyager 1 on a special mission to examine Titan’s thick atmosphere up close. Twenty years later, NASA doubled down on this interest with the Cassini mission, which explored the Saturn system as a whole. Cassini also carried a dedicated lander, the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe, which touched down Jan. 14, 2005, in Titan’s equatorial region. Huygens returned tantalizing data about this primordial moon, including a treasure trove of information about its thick atmosphere that we are still unpacking 20 years later.

Related: How we landed a probe on another planet’s moon

But Titan’s diameter is only 40 percent that of Earth, and it has less than 2.3 percent of Earth’s mass. With this in mind, how can it hold onto such a dense atmosphere, especially over the course of many millions of years? Mars, for example, is believed to be dry and barren today because the solar wind stripped away its atmosphere at some point in the ancient past. So why hasn’t this happened to Titan?

The Southwest Research Institute’s Kelly Miller offers another layer to the mystery. “One of the many cool things about Titan is its very thick atmosphere, which is mostly nitrogen,” she says. “But it also has an important five percent or so of methane. And methane participates in photochemical reactions (reactions caused by sunlight) that generate aerosol material, which sediments down and probably contributes to the organic material that covers a lot of Titan’s surface.”

But this process would rid Titan of the methane in its atmosphere in only about 30 million years. So how has all that methane stuck around?

Inside out

Luckily, Miller also has clues for how to answer this conundrum. She’s headed up new research in partnership with scientists at the Earth and Planets Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution for Science that suggests a possible mechanism by which the methane in Titan’s atmosphere has actually been replenished from an internal reservoir.

“Data from the Cassini-Huygens mission shows that there is argon-40 in the atmosphere,” explains Miller. “Argon-40 is a decay product from potassium-40, and potassium is a rock-forming element. So, we wouldn’t expect it to really be present so much in the ice shell. It should be present more in the rocky interior.”

With this in mind, the results of her team’s experiments, which show that organic matter in the interior of Titan could interact at high temperatures (approximately 480 F [250 C] or more), indicate that cryovolcanism may be present on Titan. Researchers have long suspected this, but the new research shows it as more likely than ever before.

If cryovolcanoes are pumping methane into Titan’s atmosphere from within, it means there must be a process in the interior to produce that methane in the first place — a situation that has other implications as well. “If this cooking process is happening in the interior with this accreted, complex organic material, then it’s going to be generating other products,” says Miller. “Also, it’s not going to be just methane and carbon dioxide created, and those other products might have some implications for whether Titan’s subsurface ocean could be habitable or not.”

Hoping for answers

Of course, there is still plenty left to discover about Titan. For starters, where exactly did the deep reservoir of methane in its interior come from? This and other questions may be answered by upcoming missions to Titan, including NASA and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory’s Dragonfly. The Dragonfly spacecraft, a nuclear-powered octocopter drone that will be able to fly from one scientific investigation to another, is due to launch later this decade and arrive sometime in 2034. When it arrives, it will explore Titan’s equatorial dune seas for evidence of what makes the moon the way it is.

Dragonfly, and recent efforts like the OSIRIS-REx mission to return samples from asteroid Bennu, have shown the value of focusing our analysis on the organic components in the outer solar system, and Miller expresses hope for what this means to the future of planetary science. “There’s been kind of an explosion of interest in the outer solar system community in this organic material, and what folks are discovering about these samples is going to keep growing and really, really take off.”

As lab experiments and robotic missions continue to advance our knowledge, it’s all but certain that we will come to see Titan in a whole new light.