The project team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, has reluctantly pronounced the mission at an end after being unable to communicate with the spacecraft for over a month. The last communication with the probe was August 8. Deep Impact was history’s most traveled comet research mission, going about 4.71 billion miles (7.58 billion kilometers).

“Deep Impact has been a fantastic, long-lasting spacecraft that has produced far more data than we had planned,” said Mike A’Hearn from the University of Maryland in College Park. “It has revolutionized our understanding of comets and their activity.”

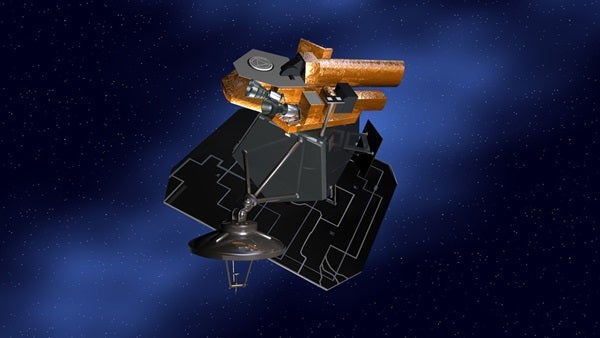

Deep Impact successfully completed its original bold mission of six months in 2005 to investigate both the surface and interior composition of a comet, and a subsequent extended mission of another comet flyby and observations of planets around other stars that lasted from July 2007 to December 2010. Since then, the spacecraft has been continually used as a space-borne planetary observatory to capture images and other scientific data on several targets of opportunity with its telescopes and instrumentation.

Launched in January 2005, the spacecraft first traveled about 268 million miles (431 million kilometers) to the vicinity of Comet 9P/Tempel 1. On July 3, 2005, the spacecraft deployed an impactor into the path of the comet to essentially be run over by its nucleus July 4. This caused material from below the comet’s surface to be blasted out into space, where it could be examined by the telescopes and instrumentation of the flyby spacecraft. Sixteen days after that comet encounter, the Deep Impact team placed the spacecraft on a trajectory to fly back past Earth in late December 2007 to put it on course to encounter another comet, 103P/Hartley in November 2010.

“Six months after launch, this spacecraft had already completed its planned mission to study Comet Tempel 1,” said Tim Larson from JPL. “But the science team kept finding interesting things to do, and through the ingenuity of our mission team and navigators and support of NASA’s Discovery Program, this spacecraft kept it up for more than eight years, producing amazing results all along the way.”

The spacecraft’s extended mission culminated in the successful flyby of Comet Hartley 2 on November 4, 2010. Along the way, it also observed six different stars to confirm the motion of planets orbiting them and took images and data of Earth, the Moon, and Mars. These data helped confirm the existence of water on the Moon and attempted to confirm the methane signature in the atmosphere of Mars. One sequence of images is a breathtaking view of the Moon transiting across the face of Earth.

In January 2012, Deep Impact performed imaging and accessed the composition of distant Comet Garradd (C/2009 P1). It took images of Comet ISON (C/2012 S1) this year and collected early images of ISON in June.

After losing contact with the spacecraft last month, mission controllers spent several weeks trying to uplink commands to reactivate its onboard systems. Although the exact cause of the loss is not known, analysis has uncovered a potential problem with computer time tagging that could have led to loss of control for Deep Impact’s orientation. That would then affect the positioning of its radio antennas, making communication difficult, as well as its solar arrays, which would in turn prevent the spacecraft from getting power and allow cold temperatures to ruin onboard equipment, essentially freezing its battery and propulsion systems.

“Despite this unexpected final curtain call, Deep Impact already achieved much more than ever was envisioned,” said Lindley Johnson, the Discovery Program executive at NASA Headquarters. “Deep Impact has completely overturned what we thought we knew about comets and also provided a treasure trove of additional planetary science that will be the source data of research for years to come.”