In a previous Herschel study, scientists found that the dusty belt surrounding nearby star Fomalhaut must be maintained by collisions between comets.

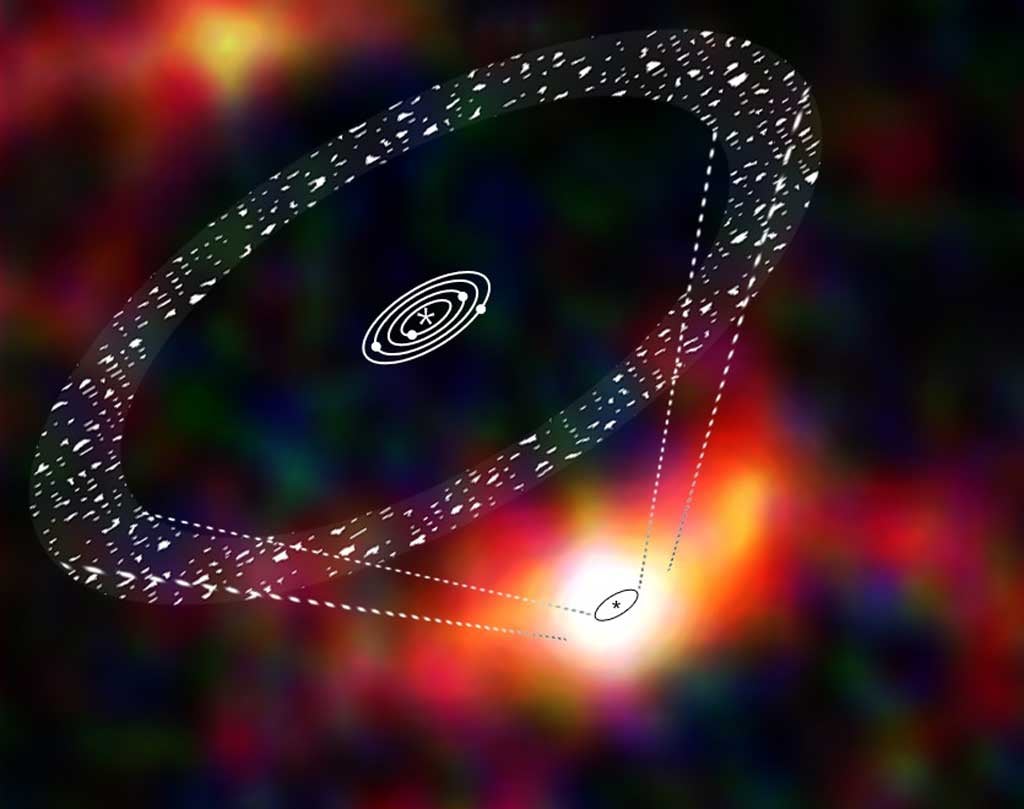

In the new Herschel study, two more nearby planetary systems — GJ 581 and 61 Vir — have been found to host vast amounts of cometary debris.

Herschel detected the signatures of cold dust at –392° Fahrenheit (–200° Celsius), in quantities that mean these systems must have at least 10 times more comets than in our solar system’s Kuiper Belt.

GJ 581, or Gliese 581, is a low-mass M dwarf star, the most common type of star in the galaxy. Earlier studies have shown that it hosts at least four planets, including one that resides in the “Goldilocks Zone” — the distance from the central sun where liquid surface water could exist.

Two planets are confirmed around G-type star 61 Vir, which is just a little less massive than our Sun.

The planets in both systems are known as “super-Earths,” covering a range of masses between two and 18 times that of Earth.

Interestingly, however, there is no evidence for giant Jupiter- or Saturn-mass planets in either system.

The gravitational interplay between Jupiter and Saturn in our solar system is thought to have been responsible for disrupting a once highly populated Kuiper Belt, sending a deluge of comets toward the inner planets in a cataclysmic event that lasted several million years.

“The new observations are giving us a clue: They’re saying that in the solar system we have giant planets and a relatively sparse Kuiper Belt, but systems with only low-mass planets often have much denser Kuiper belts,” said Mark Wyatt from the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom.

“We think that may be because the absence of a Jupiter in the low-mass planet systems allows them to avoid a dramatic heavy bombardment event and instead experience a gradual rain of comets over billions of years.”

“For an older star like GJ 581, which is at least 2 billion years old, enough time has elapsed for such a gradual rain of comets to deliver a sizable amount of water to the innermost planets, which is of particular importance for the planet residing in the star’s habitable zone,” said Jean-Francois Lestrade of Paris Observatory.

However, in order to produce the vast amount of dust seen by Herschel, collisions between the comets are needed, which could be triggered by a Neptune-sized planet residing close to the disk.

“Simulations show us that the known close-in planets in each of these systems cannot do the job, but a similarly-sized planet located much further from the star — currently beyond the reach of current detection campaigns — would be able to stir the disk to make it dusty and observable,” said Lestrade.

“Herschel is finding a correlation between the presence of massive debris disks and planetary systems with no Jupiter-class planets, which offers a clue to our understanding of how planetary systems form and evolve,” said Göran Pilbratt from ESA.

In a previous Herschel study, scientists found that the dusty belt surrounding nearby star Fomalhaut must be maintained by collisions between comets.

In the new Herschel study, two more nearby planetary systems — GJ 581 and 61 Vir — have been found to host vast amounts of cometary debris.

Herschel detected the signatures of cold dust at –392° Fahrenheit (–200° Celsius), in quantities that mean these systems must have at least 10 times more comets than in our solar system’s Kuiper Belt.

GJ 581, or Gliese 581, is a low-mass M dwarf star, the most common type of star in the galaxy. Earlier studies have shown that it hosts at least four planets, including one that resides in the “Goldilocks Zone” — the distance from the central sun where liquid surface water could exist.

Two planets are confirmed around G-type star 61 Vir, which is just a little less massive than our Sun.

The planets in both systems are known as “super-Earths,” covering a range of masses between two and 18 times that of Earth.

Interestingly, however, there is no evidence for giant Jupiter- or Saturn-mass planets in either system.

The gravitational interplay between Jupiter and Saturn in our solar system is thought to have been responsible for disrupting a once highly populated Kuiper Belt, sending a deluge of comets toward the inner planets in a cataclysmic event that lasted several million years.

“The new observations are giving us a clue: They’re saying that in the solar system we have giant planets and a relatively sparse Kuiper Belt, but systems with only low-mass planets often have much denser Kuiper belts,” said Mark Wyatt from the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom.

“We think that may be because the absence of a Jupiter in the low-mass planet systems allows them to avoid a dramatic heavy bombardment event and instead experience a gradual rain of comets over billions of years.”

“For an older star like GJ 581, which is at least 2 billion years old, enough time has elapsed for such a gradual rain of comets to deliver a sizable amount of water to the innermost planets, which is of particular importance for the planet residing in the star’s habitable zone,” said Jean-Francois Lestrade of Paris Observatory.

However, in order to produce the vast amount of dust seen by Herschel, collisions between the comets are needed, which could be triggered by a Neptune-sized planet residing close to the disk.

“Simulations show us that the known close-in planets in each of these systems cannot do the job, but a similarly-sized planet located much further from the star — currently beyond the reach of current detection campaigns — would be able to stir the disk to make it dusty and observable,” said Lestrade.

“Herschel is finding a correlation between the presence of massive debris disks and planetary systems with no Jupiter-class planets, which offers a clue to our understanding of how planetary systems form and evolve,” said Göran Pilbratt from ESA.