Why don’t Saturn’s rings throw a shadow onto the planet’s surface, like its moons do?

John Grimley

Toronto, Ontario

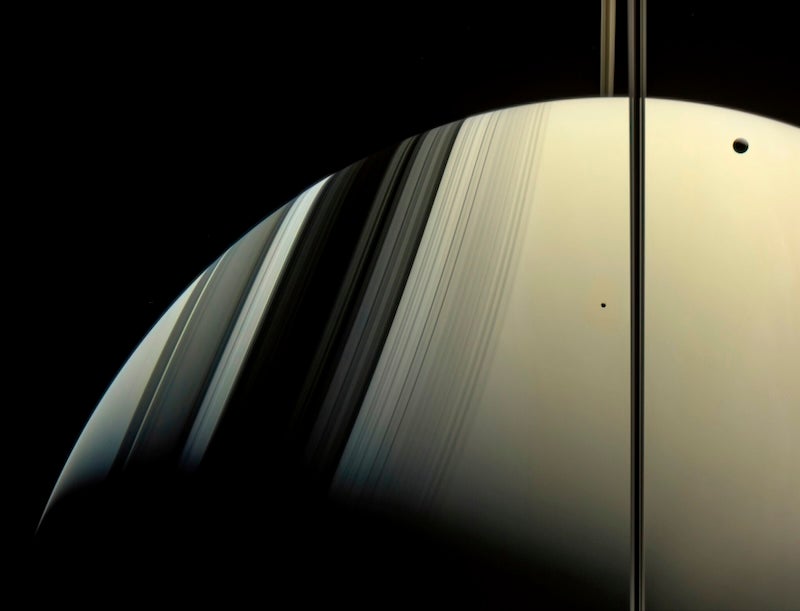

The simple answer is that Saturn’s rings do cast shadows on the planet’s surface! NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, took the dramatic image of the rings’ shadows on Saturn shown above.

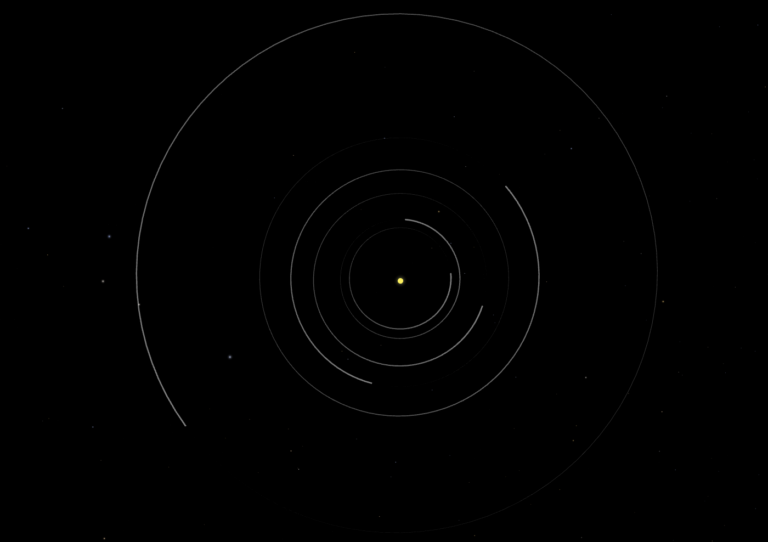

The major parts of Saturn’s inner massive rings are visible in the image below. The rings consist of huge numbers of mostly icy particles ranging from centimeters to many meters in size, plus dust and a few larger embedded moonlets. Their combined mass is similar to that of Saturn’s moon Mimas. All these particles orbit Saturn in Saturn’s equatorial plane. The particles do not emit visible light of their own but reflect and scatter sunlight. In some parts of the rings the particles are packed more densely than in others, which affects how bright they look because of scattered light and how dark their shadows are. In the same image, the more densely packed parts of the rings, like the A and B rings, are brighter because they backscatter more sunlight, while the Cassini division and the C Ring are dimmer. (There are a few dark gaps where there is little material.)

For an Earth-based observer, however, the ring shadows can be difficult to notice for two reasons. First, the rings themselves can get in the way of seeing the shadows from our perspective. Second, at times when we do get a glimpse of the shadows, one needs a decent telescope and good seeing to notice them.

Saturn is 10 times farther from the Sun than Earth. So, as seen from Saturn, Earth is always nearly in the same direction as the Sun, within about 6°. As a result, the bright face of the rings gets in the way of seeing the ring shadows from Earth.

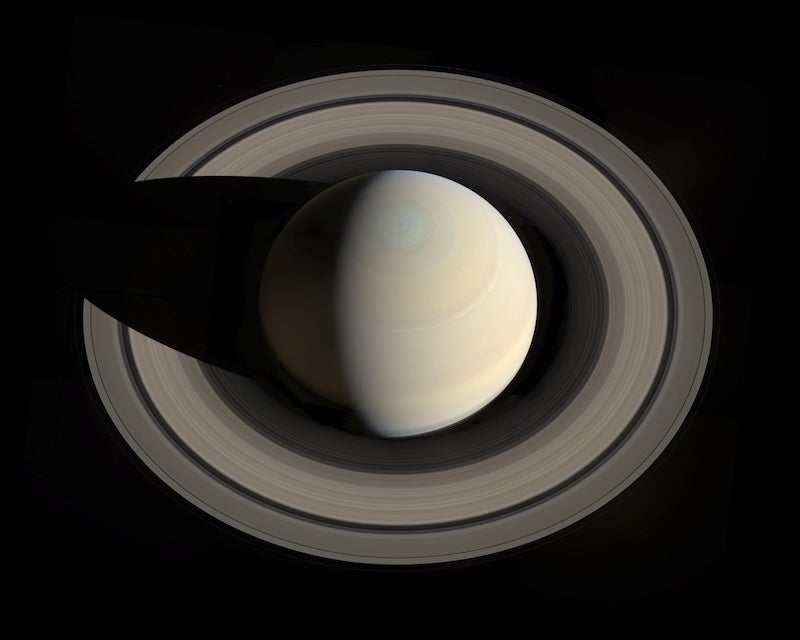

Saturn’s rotation axis is tilted with respect to its orbital plane around the Sun by about 26.7° — not too different from Earth’s 23.5°. Like a spinning top, the orientation of Saturn’s axis and the equatorial rings remain relatively fixed in space. So, twice per orbit, the rings are edge-on to the Sun and produce only a slender shadow across Saturn’s equator. Between these edge-on events, for about half the orbit, the northern face of the rings tilts toward the Sun, casting shadows on Saturn’s southern hemisphere; for the other half, the southern ring face is toward the Sun and shadows are cast on Saturn’s northern hemisphere. The extent of the ring shadows on the planet varies quite a bit depending on the tilt of the rings relative to the Sun.

At times near maximum tilt of the rings to the Sun, the shadows produced by the rings cover a large part of the daylight side of Saturn, as shown in the image at the top of this page — but at those times, the bright face of the rings hides the extensive shadows for an observer on Earth.

This spectacular Cassini image was taken just a few years after the maximum opening of the rings to the Sun that occurred in 2002 (seen from Earth, this maximum happens roughly every 15 years). Using gravitational assists from Saturn’s moons, Cassini regularly changed its orbit around Saturn, resulting in a wide variety of perspectives on the ring shadows, as illustrated by many images you can find from the mission.

The second reason, seeing, refers to how much small fluctuations in Earth’s atmosphere blur our view of astronomical objects. “Good” seeing refers to when these fluctuations are relatively mild, but good seeing is almost as hard to find these days as views free of light pollution. That’s one reason professional optical telescopes are on mountaintops or placed in orbit or on interplanetary spacecraft like Cassini.

So even an observer on Earth with a decent telescope can have a hard time actually seeing the rings’ shadows. Let’s quantify that. Really good seeing, which is again hard to come by, will blur a star by one second of arc (1″) in angle. Saturn is only 15″ to 20″ in diameter as seen from Earth. And the glimpses we get of the ring shadows from Earth during times of minimum ring tilt can be thinner than an arcsecond. (See “A Saturn ring mirage” in the November 2024 issue for more details about making such a challenging observation.)

Richard H. Durisen and Paul R. Estrada

Professor Emeritus of Astronomy, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana,

and Research Scientist, NASA Ames Research Center, Mountain View, California