That’s the finding of a group of researchers who’ve just completed the first scientific analysis of rock cores collected from the central part of the Chicxulub impact crater off the coast of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

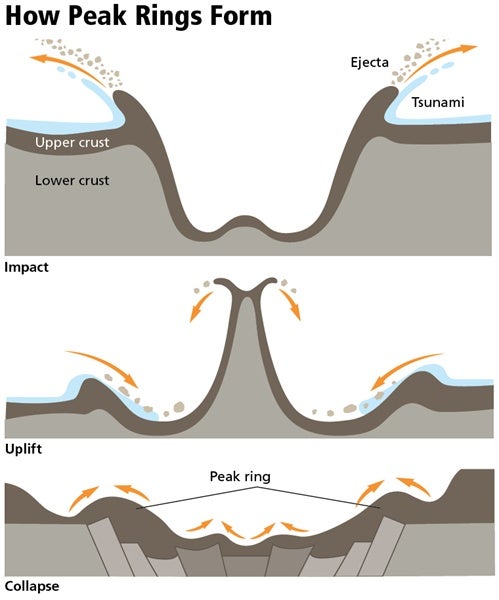

This spring, an international team used an offshore drilling platform to core thousands of feet below the ocean floor. They tapped into the crater’s central peak ring, a rocky set of inner ridges or hills that formed during the impact. Then those samples were taken to the International Ocean Discovery Program Core Repository in Bremen, Germany, where scientists examined the rocks for weeks on end.

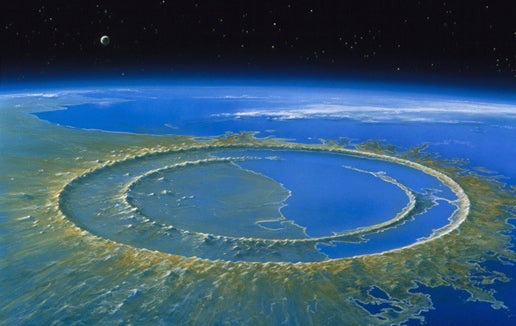

Scientists had multiple peak ring formation theories, but the more than 100-mile-wide Chicxulub crater is the only impact site on Earth with its central rings still intact. Similar large craters on the Moon and other planets are inaccessible.

In a paper published Thursday in Science, the team, led by Joanna Morgan of Imperial College London and Sean Gulick of the University of Texas at Austin, paired seismic data with results from the core samples. Their study shows that peak rings form when an asteroid impact excavates rock from deep below a world’s surface and then that material bounces back up in the center before collapsing into rings.

But the results also carry implications for the vary existence of life. Scientists don’t fully understand how organisms survived Earth’s early and violent history, when asteroids and comets regularly pummeled the planet’s surface. Chicxulub’s peak rings show that the impact deformed the peak ring rocks and made them more porous and less dense than expected, creating a nutrient-rich home for simple organisms. And the impact would have left the crater bubbling hot for hundreds of thousands of years afterward, giving them sufficient time to adapt and evolve.

“It is hard to believe that the same forces that destroyed the dinosaurs may have also played a part, much earlier on in Earth’s history, in providing the first refuges for early life on the planet,” says Morgan. “We are hoping that further analyses of the core samples will provide more insights into how life can exist in these subterranean environments.”

Discover associate editor Eric Betz visited the Chicxulub drill site in April. You can read his feature about the expedition here.

This article originally appeared on Discover.