A favorite object of many backyard and professional astronomers alike, planetary nebulae are some of the most beautiful objects in the universe. Puffed out into wildly psychedelic shapes and colors, these shells of gas mark the spectacular final act of a lone dying star — at least this is what scientists thought was going on. Now, surprising new observations point to a more bizarre and complex birth for some of these cosmic bubbles, making astronomers see double.

Using the Wisconsin-Indiana-Yale-NOAO (WIYN) 3.5-meter telescope at the Kitt Peak National Observatory to peer into the hearts of nearly a dozen planetary nebulae, a team of American scientists has found convincing evidence that most of these gas clouds harbor binary stars in their centers. The radial velocity measurements for ten out of eleven central stars revealed the telltale wobble signifying the gravitational tug of an unseen companion star.

“If our current results are confirmed with further observations, we could be at the start of a revolution in the study of the origin of planetary nebulae,” says team leader Howard Bond of the Space Telescope Science Institute. “If these nebulae arise from binary stars, it implies a very different origin for these systems than what most astronomers had thought.”

It is widely acknowledged that Sun-like stars end their days by shedding most of their atmosphere into a gaseous cocoon — but Bond and his colleagues believe binary stars play a crucial role in planetary nebula formation. The team’s unexpected results reveal double star systems may affect how stellar remnants are thrown out into space, leading to many of the more exotic morphologies.

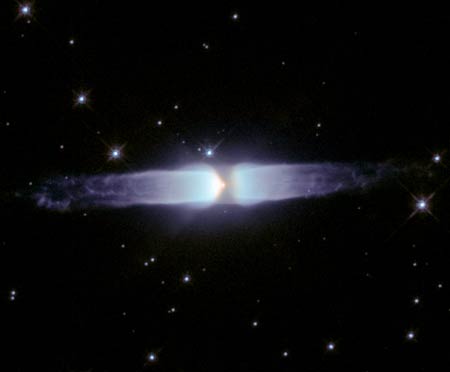

While planetary nebulae can thank bloated red-giant stars for their initial creation, the stars’ spin rates and associated magnetic fields cannot account for the creation of some of the more complex shapes seen in nebulae. The Hubble Space Telescope’s gallery of greatest images shows off a kaleidoscope of gas bubbles in all shapes and symmetries. Many of the more picturesque planetary nebulae often appear elliptical, with lobe-like structures attached to jet-like extensions. The enigmatic structures of these nebulae, however, have puzzled astronomers and challenged existing theories.

“The most direct way to spin up these vast, fluffy stars is by the action of an orbiting companion. In extreme cases, as a red giant star gradually increases in size, it may actually swallow a companion star, which would then spiral down inside the giant and eventually eject its outer layers,” describes Orsola De Marco, an astronomer at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and coauthor of the study. “Despite this, the mainstream astronomical view remains rooted in single-star theories for the evolution of planetary nebulae, supported by the small percentage of planetary nebulae central stars that were previously known to be binaries. However, our new research threatens to turn this viewpoint on its head.”

Reporting their results in the February 1 issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters, the team hopes to find more candidate sources. In order to rule out the possibility of any physical sources that may be only mimicking the stellar wobble, they will attempt to pin down precise orbital periods for these binary stars. DeMarco adds: “We are reasonably sure that these variations are due to binarity, but determination of their precise periods is the only way to be sure.”