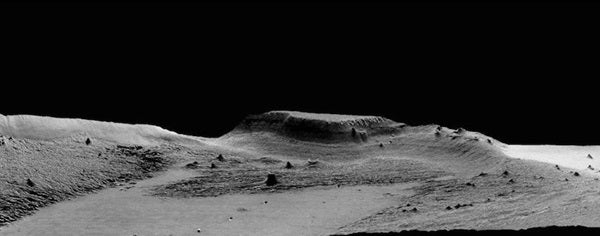

New research published in the journal Nature Communications revealed that the massive amounts of dust are tied to Mars’ Medusae Fossae Formation (MFF), the largest explosive volcanic ash deposit in the solar system. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University found that Martian winds are gradually eroding the volcanic remnants, which cemented in place billions of years ago. The winds transform them into the fine dust particles that take over the planet during global and seasonal storms.

NASA’s Mariner Spacecraft first discovered the 1.25 million square mile (2 million square kilometer) formation in the 1960s, but its origins remained a mystery until recently. Researchers could tell from radar imaging that it had a strange composition, but they weren’t sure if water, ice, wind or a volcanic activity caused the peculiar structure. However, research published in May used gravity data from multiple Mars orbiters to measure the density of the formation. The results showed that it’s only about two thirds as dense as your typical Martian surface and that it doesn’t contain any ice — a composition that can only be explained by volcanic eruptions.

And because of its porous nature, the MFF has fallen victim to Martian winds and significant erosion over the years. When remnants of powerful volcanic eruptions formed the structure over 3 billion years ago, it was about half the size of the United States. Now, it would cover just 20 percent of the U.S. So where did all of its sediment go?

And based on its erosion rate, the scientists were able to calculate the amount of dust on Mars’ surface. They found that there’s enough to cover the entire planet in roughly six to 40 feet (2 to 12 meters) of sediment. And the dust will keep building up as Medusae Fossae continues to erode.

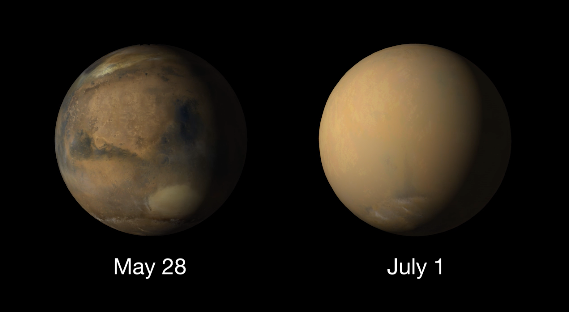

The increasing amount of dust not only causes thicker storms, but it also contributes to their intensity. The dust absorbs some of Mars’ solar radiation, which causes surface temperatures to decrease and atmospheric temperatures to increase. These temperature variations make winds stronger than usual, releasing even more dust that gusts across the surface during storms.

These conditions may have created a powerful global dust storm during our prime time for viewing Mars in the night sky, but the unfortunate coincidence wasn’t exactly a surprise. Global storms pop up every six to eight years or so, and it just so happened to interrupt Mars at its brightest this time around. But at the end of the day, we’ve gained crucial knowledge of the Red Planet’s history and finally know the source of the swirling, engulfing dust that’s blocking our otherwise wondrous view.

This article originally appeared on Discovermagazine.com.