Haumea has two known satellites, an unusually high spin rate, and is also the “parent” of a large family of icy bodies in the outer solar system that used to be chunks of its surface, but which now orbit the Sun on their own. These unique features are indicative of an ancient collision, making Haumea one of the most interesting objects in the Kuiper Belt, said Darin Ragozzine from Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne.

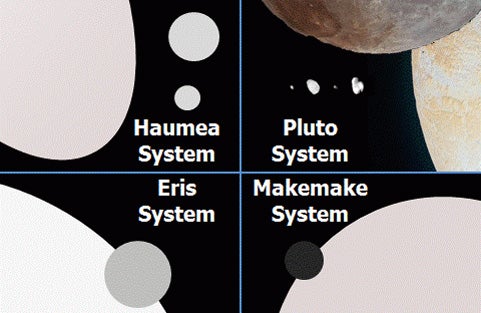

Pluto and Haumea are the only outer system bodies with more than one moon. Pluto boasts the large moon Charon and four tiny satellites. The other known KBO dwarf planets, Eris and Makemake, have a medium and tiny moon, respectively. Makemake’s moon was discovered in April.

But beyond its two known medium-sized satellites, Haumea doesn’t seem to have small, icy moons similar to Pluto’s. “While we’ve known about Pluto’s and Haumea’s moons for years, we now know that Haumea does not share tiny moons like Pluto’s, increasing our understanding of this intriguing object,” said Ragozzine.

The observations also seem to imply that, despite some similarities, the satellite systems of the icy dwarf planets had different pathways to their formation. Even with the new result, Ragozzine emphasized that both Pluto and Haumea moon systems have the planetary science community stumped. “There is no self-consistent formation hypothesis for either set of satellites.”

The Haumea observations were made with the Hubble Space Telescope, which was focused on a ten-consecutive-orbit sequence in 2010. The hunt for extra moons around Haumea relied on a novel technique labeled the “non-linear shift-and-stack” method, an approach that may be useful for other satellite searches or detecting yet-unknown Kuiper Belt objects.

As continued analyses of NASA New Horizons observations of Pluto roll in, Ragozzine is seeking funding to try to get to the bottom of Haumea. The new understanding that the dwarf planet doesn’t have tiny moons and exhibits other unusual characteristics adds to the puzzle.