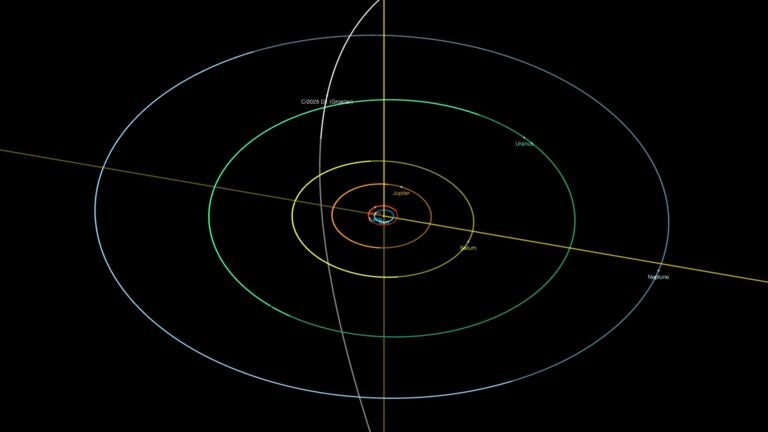

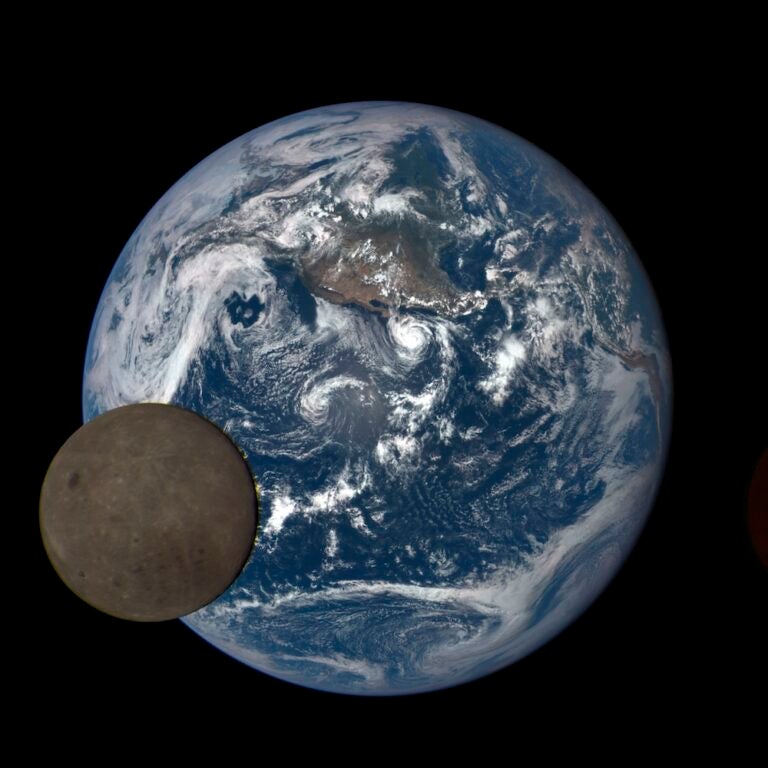

A binary asteroid named 1999 KW4 passed some 32 million miles (5.2 million km) from Earth on May 25, giving astronomers a good look at a space rock that won’t come this close again for nearly two decades. The flyby brought it about 14 times farther away than our Moon, but still close enough for astronomers to study.

The International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN) organized the campaign, which included the European Space Agency, NASA, and the National Science Foundation to observe the asteroid. The asteroid is less than a mile in diameter (1.3 km) with a small “moon” following, and poses no real direct threat to Earth, though it’s still classified as “potentially hazardous,” according to Goldstone Radar Observations Planning.

But even though 1999 KW4 isn’t inherently dangerous, it looks a lot like another binary asteroid system that could pose a future threat. Looking toward 2022, NASA plans to try and slightly change the orbit of Didymos, a binary asteroid system that, while unlikely, could potentially pose a threat to Earth.

As Didymos passes close to Earth, NASA will arrive with a spacecraft to carry out their Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART). The DART mission will be the first attempt to change the motion of an asteroid in space. NASA hopes that the deliberate collision of DART and Didymos will change the speed of the asteroid by a fraction of one percent. This will slow the orbit of Didymos by a few minutes, allowing astronomers to study Didymos better and rehearse what to do if there’s an asteroid that poses a massive threat to Earth.

“In the worst possible case, this knowledge is also essential to predict how an asteroid could interact with the atmosphere and Earth’s surface, allowing us to mitigate damage in the event of a collision,” said European Southern Observatory (ESO) astronomer, Oliver Hainaut in a press release.

To track 1999 KW4, astronomers used the Very Large Telescope (VTL) array in Northern Chile, which used SPHERE, an instrument equipped with a specialized camera and infrared technology that is normally used to find exoplanets. Through SPHERE, scientists were able to gather images sharp enough to make out the two separate components of 1999 KW4, which were orbit each other at a distance of about 1.6 miles (2.6 km).

Observing the faint asteroid was also particularly challenging for the team. Conditions were unstable at the time and the asteroid was moving at about 43,000 mph (70,000 km/h). And, to make matters worse, the adaptive optics system — a special mirror design that lets astronomers counteract turbulent atmospheric conditions — crashed several times. Nonetheless, the team prevailed and managed to use SPHERE’s cameras to obtain the sharpest photos ever of the binary system.

It’s a good thing, too. The asteroid’s next flyby isn’t until 2036.