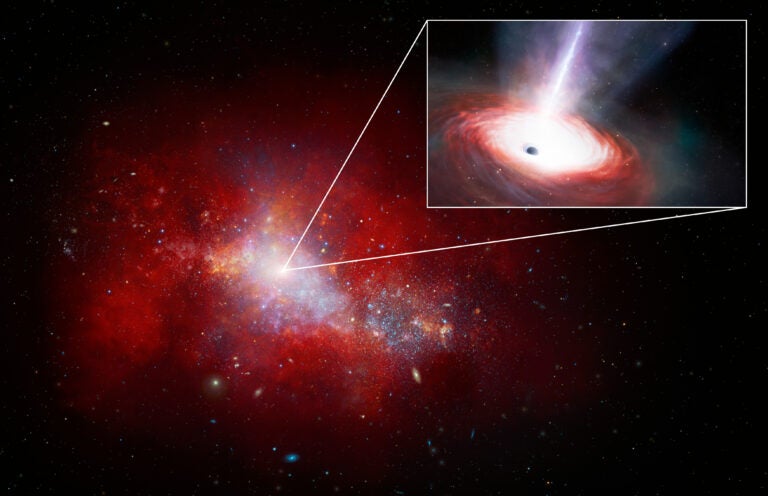

The scientists combined the Russian RadioAstron satellite with the ground-based telescopes to produce a virtual radio telescope more than 100,000 miles across. They pointed this system at a quasar called 3C 273, more than 2 billion light-years from Earth. Quasars like 3C 273 propel huge jets of material outward at speeds nearly that of light. These powerful jets emit radio waves.

Just how bright such emission could be, however, was thought to be limited by physical processes. That limit, scientists thought, was about 100 billion degrees. The researchers were surprised when their Earth-space system revealed a temperature hotter then 10 trillion degrees.

“Only this space-Earth system could reveal this temperature, and now we have to figure out how that environment can reach such temperatures,” said Yuri Kovalev, the RadioAstron project scientist. “This result is a significant challenge to our current understanding of quasar jets,” he added.

The observations also showed, for the first time, substructure caused by scattering of the radio waves by the tenuous interstellar material in our Milky Way Galaxy.

“This is like looking through the hot turbulent air above a candle flame,” said Michael Johnson of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We had never been able to see such distortion of an extragalactic object before,” he said.

“The amazing resolution we get from RadioAstron working with the ground-based telescopes gives us a powerful new tool to explore not only the extreme physics near the distant supermassive black holes, but also the diffuse material in our home galaxy,” Johnson said.

The RadioAstron satellite was combined with the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia, The Very Large Array in New Mexico, the Effelsberg Telescope in Germany, and the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Signals received by the orbiting radio telescope were transmitted to an antenna in Green Bank where they were recorded and then sent over the internet to Russia where they were combined with the data received by the ground-based radio telescopes to form the high resolution image of 3C 273.

In 1963, astronomer Maarten Schmidt of Caltech recognized that a visible-light spectrum of 3C 273 indicated its great distance, resolving what had been a mystery about quasars. His discovery showed that the objects are emitting tremendous amounts of energy and led to the current model of powerful emission driven by the tremendous gravitational energy of a supermassive black hole.