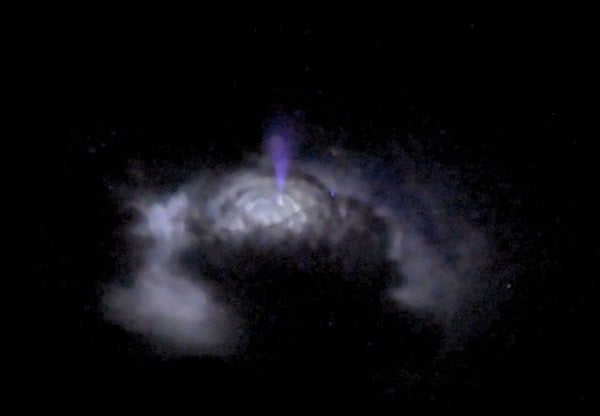

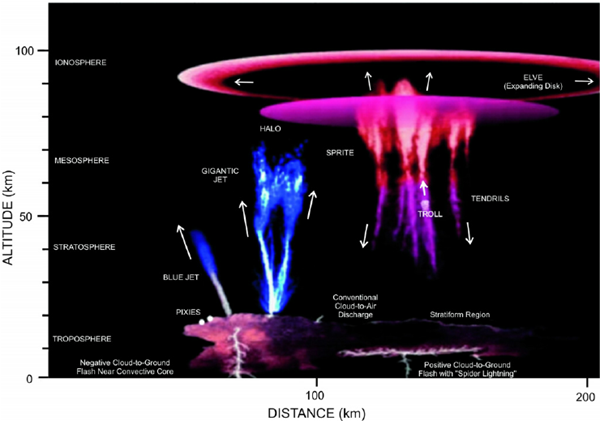

In Earth’s upper atmosphere, blue jets, red sprites, pixies, halos, trolls and elves streak toward space, rarely caught in the act by human eyes.

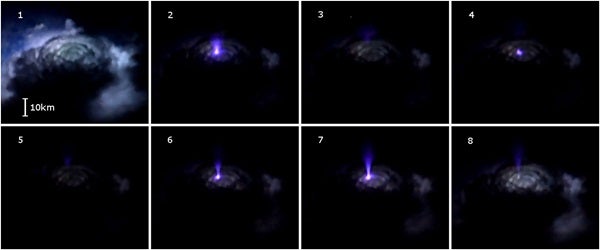

This mixed-bag of quasi-mythological terms are all names for transient luminous events, or, quite simply, forms of lightning that dance atop thunderstorm clouds. Airplane pilots have reported seeing them, but their elusive nature makes them hard to study. But ESA astronaut Andreas Morgensen, while aboard the International Space Station in September 2015, filmed hundreds of blue jets flashing over a thunderstorm that was pounding the Bay of Bengal, confirming a mysterious atmospheric phenomenon.

According to Morgensen and researchers at the Denmark National Space Institute, these observations are the first of their kind, and offer a rare glimpse of poorly understood atmospheric phenomena. His work, which was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, also proves that the ISS is a perfect lab for studying elves and pixies, and a planned follow-up mission should reveal even more.

A Great View

Storm clouds are like electrical cakes with alternating layers of negatively and positively charged ions. Air currents tear through the sky cake, squashing the layers and reversing their stacking order. When the base layer’s charge differs from the earth’s charge—zap. The seems to be true for layers higher in the atmosphere, but instead of striking earth, transient luminous events discharge into space. Of course, you need to be above the clouds to see them; thus, the reason they are difficult to study.

Scientists have since used satellites to study space lightning, but their viewing angle isn’t ideal for gathering data on sprites and jets. However, at its lower orbit, the ISS is perfectly positioned to record such events. And that was precisely to aim of the Thor experiment, which was conducted by Morgensen, the first Danish astronaut aboard the ISS. He used a Nikon D4 camera tuned to the appropriate settings, and peered out of the window of the Russian Pirs module when forecasts favored a storm.

However, scientists need to know much more about these events to formulate any firm conclusions, and they’ll get some help. Later this year, the Atmosphere-Space Interactions Monitor (ASIM) will head to the ISS to continuously monitor thunderstorms—combing the atmosphere for transient luminous events. The ASIM experiment will observe these events in two ultraviolet optical bands, as well as the X- and gamma-rays.

With imagery provided by ASIM, scientists might get a little closer to understanding the physics of these colorful flashes.

This article originally appeared on Discover.