Last month, the European Space Agency (ESA) released a huge dataset from its space telescope Euclid. The release featured three deep-field mosaics glittering with 380,000 galaxies and hundreds of examples where the light of distant objects is bent and magnified by the gravitational influence of massive galaxies.

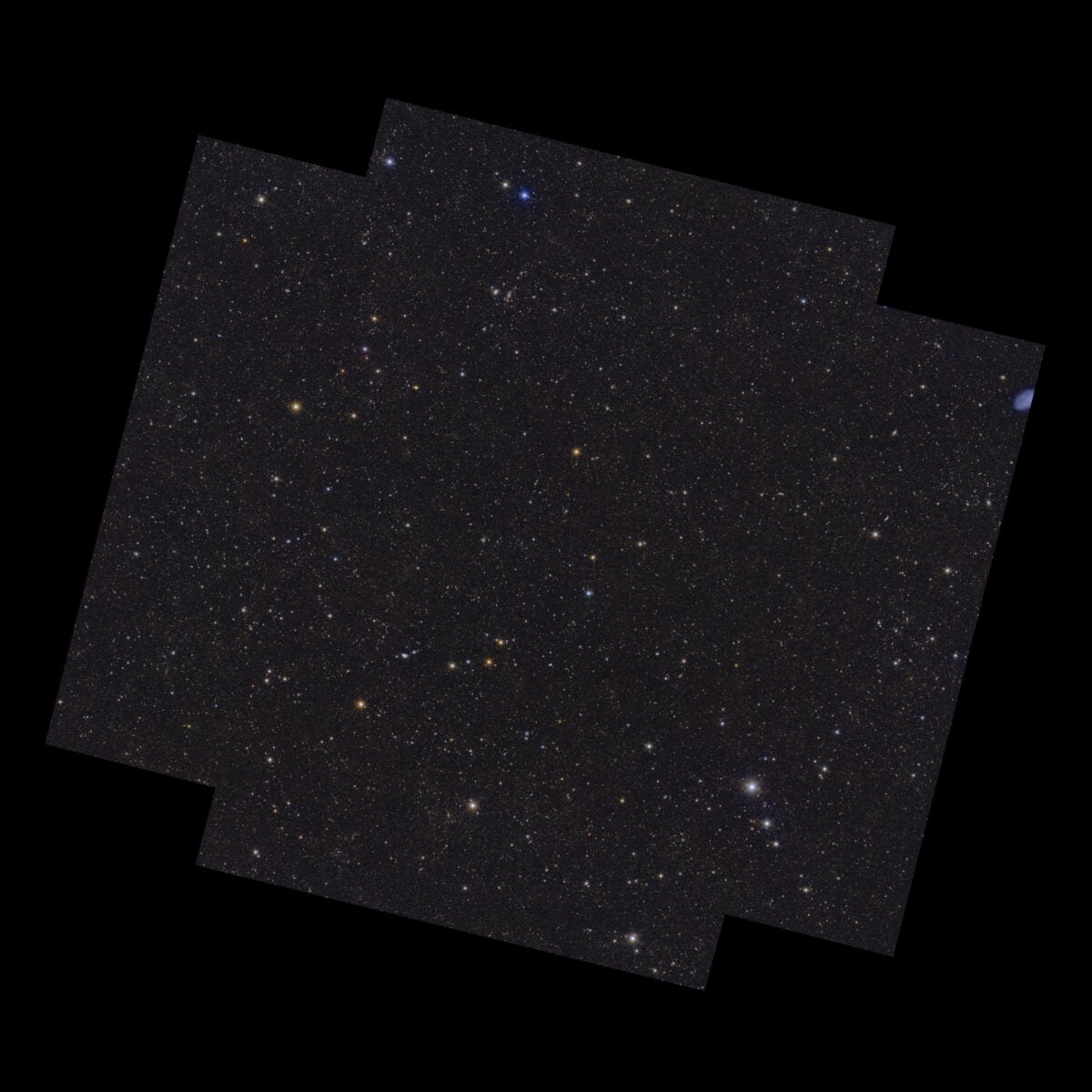

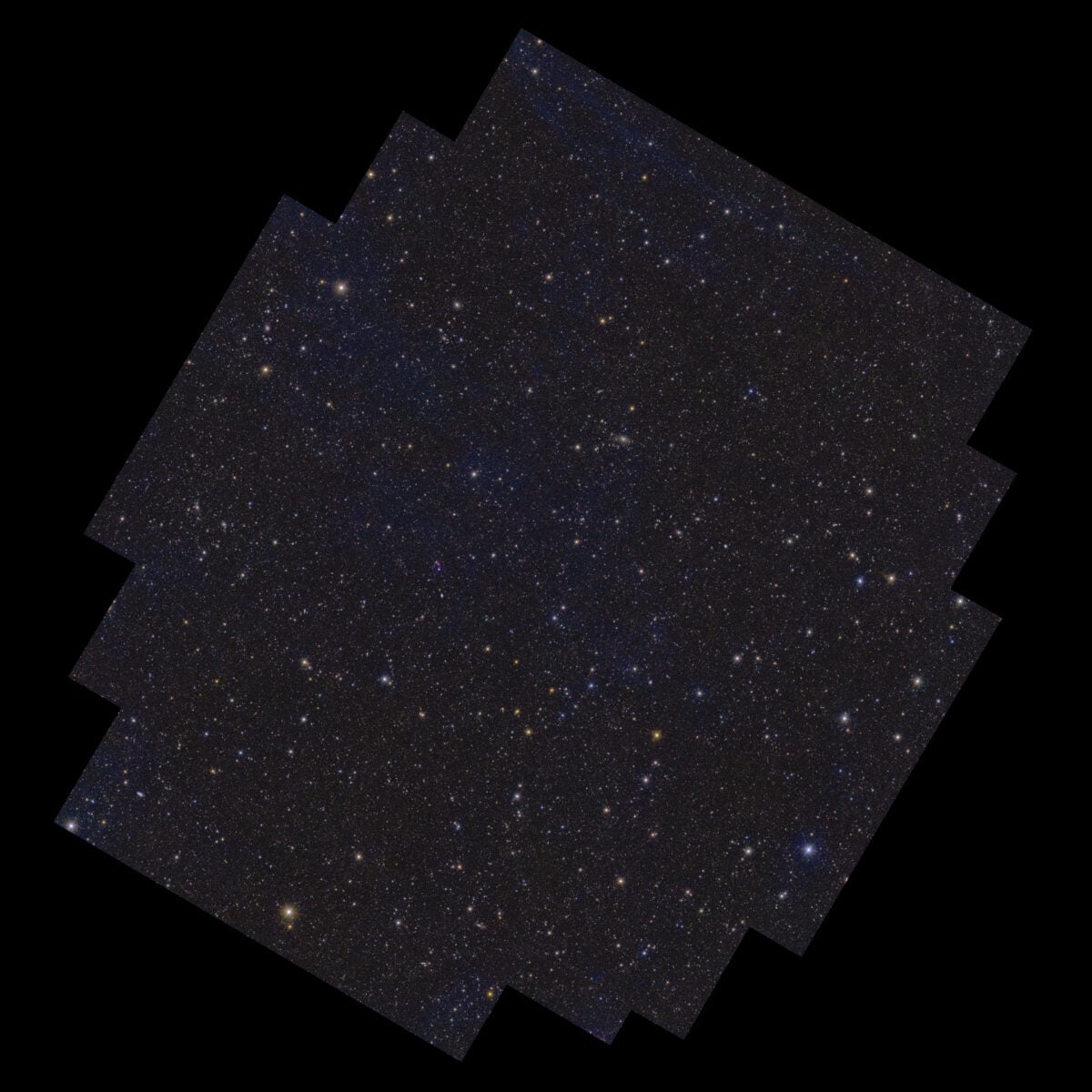

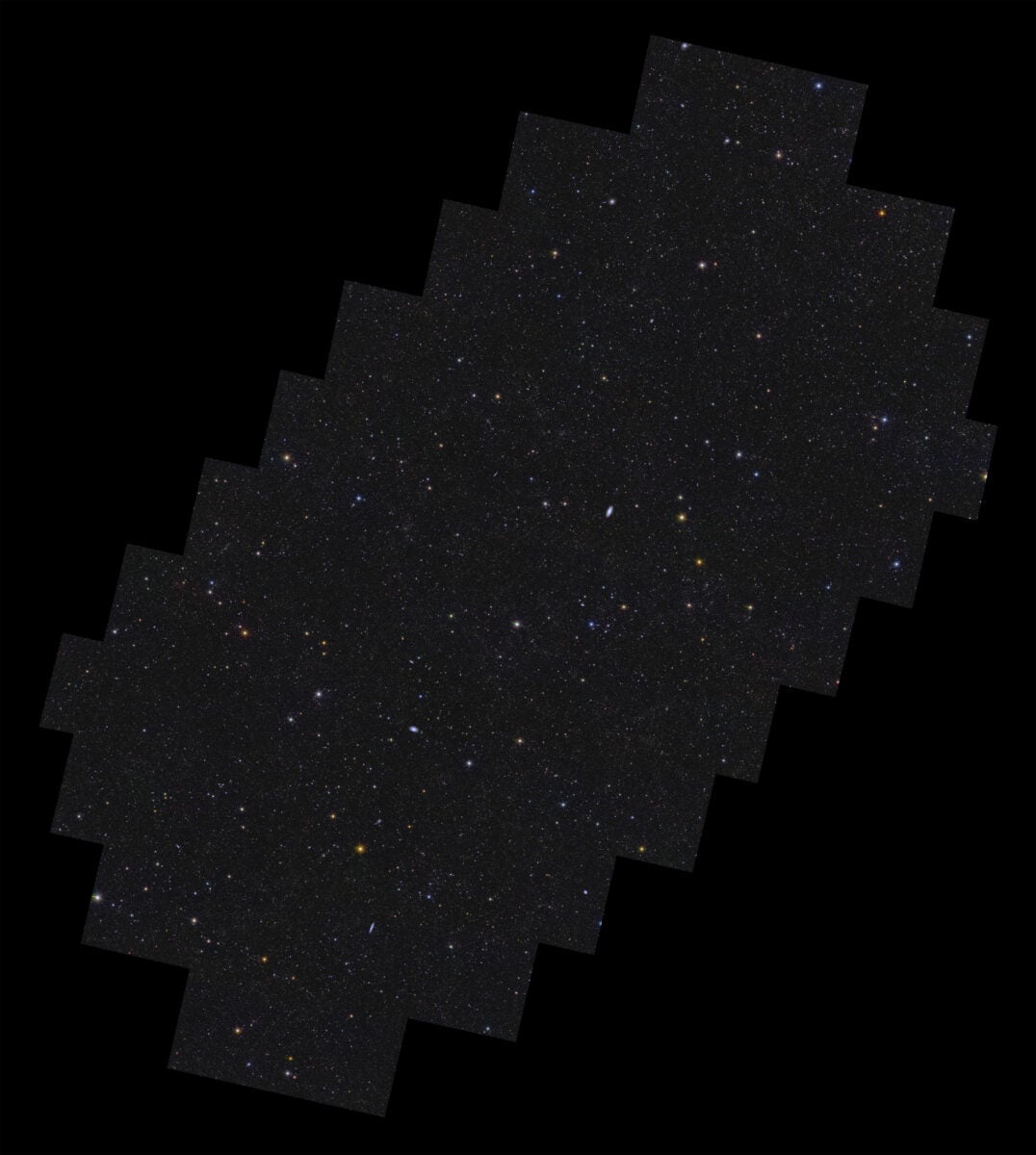

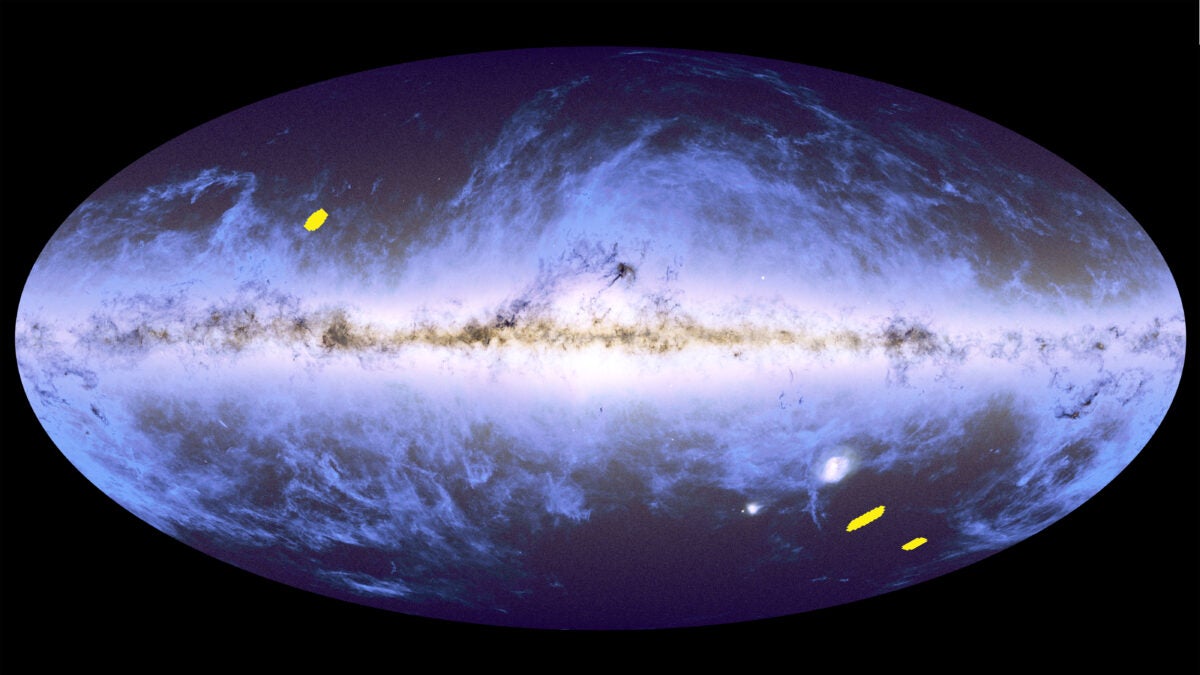

The mosaics were captured in the constellations of Fornax, Draco, and Horologium. Combined, these fields make up about 63 square degrees of the sky, equivalent to the area of more than 300 Full Moons, according to a March 19 ESA news release. That makes them the largest contiguous areas of sky ever observed with an optical and near-infrared telescope, says the Euclid team. The mission ultimately aims to map over one-third of the sky by 2030, amassing data from 14,000 square degrees. During this time, Euclid will revisit these three deep fields up to 52 more times.

The release of the data marks a significant step for the Euclid mission, which launched in 2023. Its main goal is to map and observe galaxies across cosmic time to better understand how the universe and its largest structures evolved. With the data from those galaxies, scientists hope to discover more about the nature of gravity, dark matter, and dark energy.

Scientists are still carrying out their initial cosmological analyses of the data. But the current release — what the Euclid team is calling a “quick data release” — offers the biggest glimpse yet of the telescope’s power.

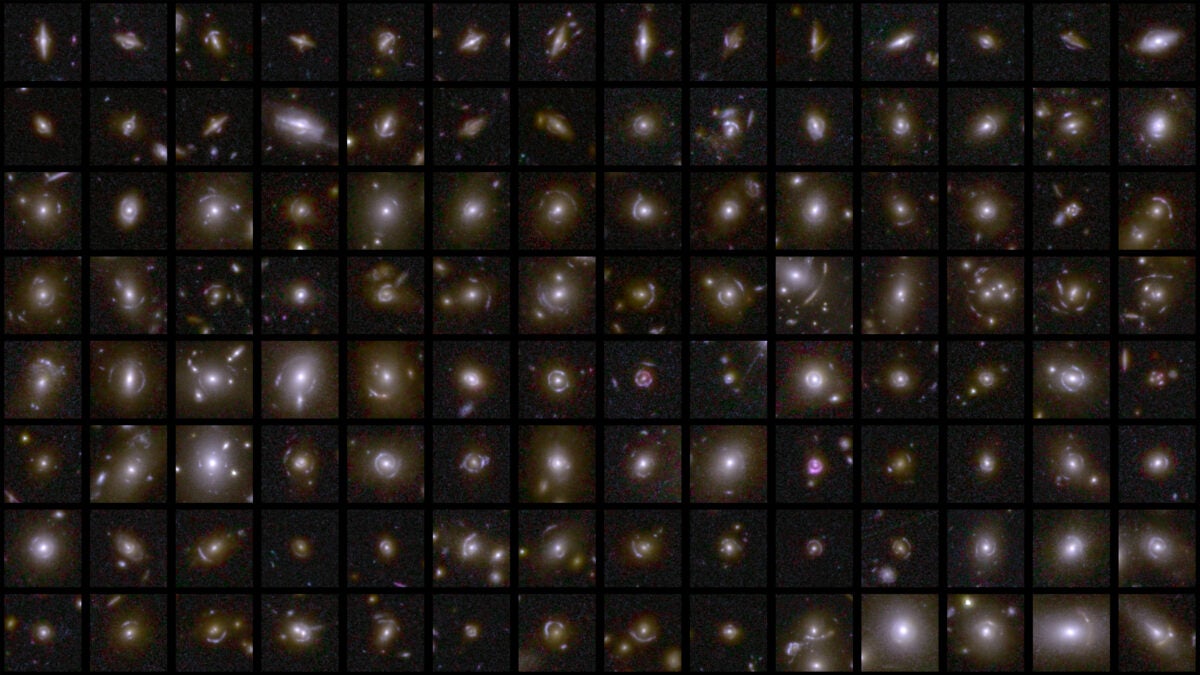

A standout feature of this data release is the number of galaxies spotted: 380,000. As this is just a fraction of what the mission is expected to observe, the Euclid team knew that classifying these objects would require the effort of more than just a handful of researchers. So last year they enlisted machine learning AI algorithms and the help of citizen scientists on the platform Galaxy Zoo to sort the galaxies based on their appearance — whether they had spiral arms, bars, and other features.

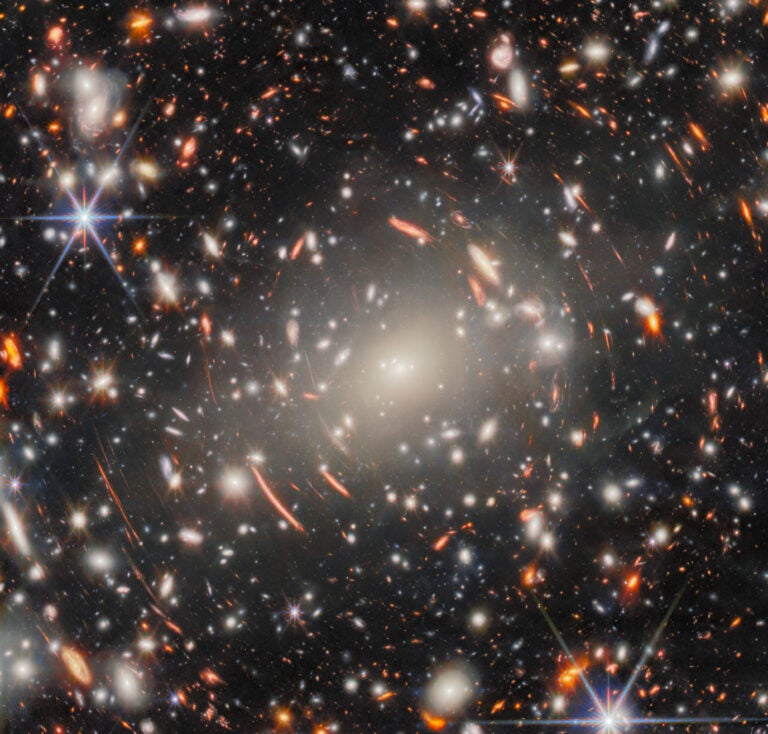

The AI and citizen scientists were also able to suss out many locations that appear to be examples of strong gravitational lensing. This is when the gravity of a foreground object is so strong that it bends the light of a more distant object behind it, magnifying and distorting the distant object’s appearance into arcs or rings (also known as Einstein rings). The collaboration found about 500 of these objects, with many more examples of weaker lensing and milder visual distortions.

“This data release highlights the incredible potential we have by combining the strengths of Euclid, AI, citizen science and experts into a single discovery engine that will be essential in tackling the vast volume of data returned by Euclid,” said Pierre Ferruit, mission manager for Euclid.

Other finds in the new data include thousands of faint dwarf galaxies, as well as thousands of massive red galaxies from the early universe. The latter — dubbed “little red dots” — have caused a minor stir among cosmologists since first being spotted in data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope in 2022, as they seem too big to have formed so early in the universe’s history. (An alternative theory suggests the excess light is actually the glow of material swirling just outside these galaxies’ central black holes).

Scientists are currently working on several papers with the Euclid mission’s first cosmological results. The team plans to publish its first full data release in October 2026.