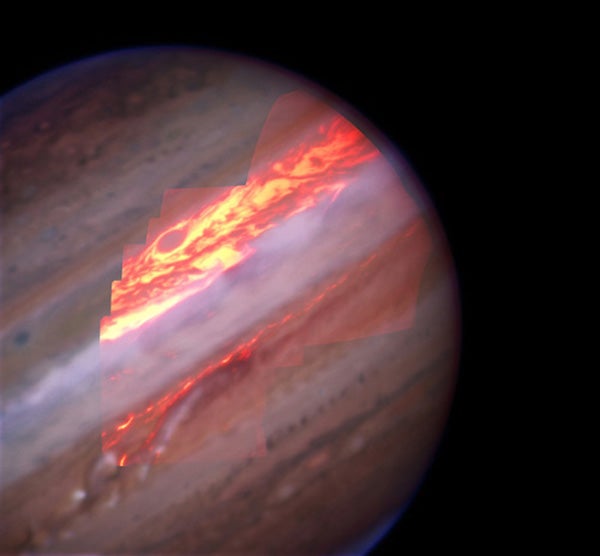

“The thermal IR senses breaks in the cloud cover,” said Mike Wong of the University of California (UC) at Berkeley. The thermal IR data is essentially showing heat from Jupiter’s interior being radiated into space. The three other IR bands, in contrast, capture reflected sunlight. Put them all together and compare them to visible-light images, and scientists get a picture of a thinning, breaking layer of high, bright, icy clouds that have obscured the brown-red SEB for about a year, making it look like a wide white zone.

“We see wispy cloud-free regions at 5 microns in the SEB, but they are much less extensive than the near-infrared dark regions surrounding them,” said Wong. “The data show that the change from zone-like to belt-like appearance is a complex process that takes place at different speeds in each layer of Jupiter’s atmosphere.”

The four-band infrared image was created using a clever twist on the Keck II telescope’s adaptive optics, which effectively cancels out much of the interference of Earth’s atmosphere. Normally, astronomers use a powerful laser to create an artificial guide star. With that, they can monitor Earth’s constantly changing atmosphere and cancel out the distortions at a rate of up to 2,000 times per second.

But Jupiter is so bright that it hides the laser guide star. The astronomers needed something brighter that was also very close to Jupiter in the sky. On November 30, 2010, the icy Jovian moon Europa was positioned just right to serve that purpose, said Franck Marchis, also of UC Berkeley and the SETI Institute.

Timing observations right so that Europa makes adaptive optics possible is no easy feat, according to Marchis, and underscores the technical challenges involved in peering into Jupiter’s clouds. Despite many other researchers watching Jupiter’s changing clouds with other telescopes, none, not even the Hubble Space Telescope, is equipped to peer in the 5-micron band with such high resolution. Marchis, Wong, and Imke de Pater from UC Berkeley are involved in a large monitoring program aimed at following up on these rare and mysterious happenings in Jupiter’s atmosphere. W. M. Keck Observatory support astronomer Randy Campbell assisted them in their Keck II observations.

“The thermal IR senses breaks in the cloud cover,” said Mike Wong of the University of California (UC) at Berkeley. The thermal IR data is essentially showing heat from Jupiter’s interior being radiated into space. The three other IR bands, in contrast, capture reflected sunlight. Put them all together and compare them to visible-light images, and scientists get a picture of a thinning, breaking layer of high, bright, icy clouds that have obscured the brown-red SEB for about a year, making it look like a wide white zone.

“We see wispy cloud-free regions at 5 microns in the SEB, but they are much less extensive than the near-infrared dark regions surrounding them,” said Wong. “The data show that the change from zone-like to belt-like appearance is a complex process that takes place at different speeds in each layer of Jupiter’s atmosphere.”

The four-band infrared image was created using a clever twist on the Keck II telescope’s adaptive optics, which effectively cancels out much of the interference of Earth’s atmosphere. Normally, astronomers use a powerful laser to create an artificial guide star. With that, they can monitor Earth’s constantly changing atmosphere and cancel out the distortions at a rate of up to 2,000 times per second.

But Jupiter is so bright that it hides the laser guide star. The astronomers needed something brighter that was also very close to Jupiter in the sky. On November 30, 2010, the icy Jovian moon Europa was positioned just right to serve that purpose, said Franck Marchis, also of UC Berkeley and the SETI Institute.

Timing observations right so that Europa makes adaptive optics possible is no easy feat, according to Marchis, and underscores the technical challenges involved in peering into Jupiter’s clouds. Despite many other researchers watching Jupiter’s changing clouds with other telescopes, none, not even the Hubble Space Telescope, is equipped to peer in the 5-micron band with such high resolution. Marchis, Wong, and Imke de Pater from UC Berkeley are involved in a large monitoring program aimed at following up on these rare and mysterious happenings in Jupiter’s atmosphere. W. M. Keck Observatory support astronomer Randy Campbell assisted them in their Keck II observations.