Key Takeaways:

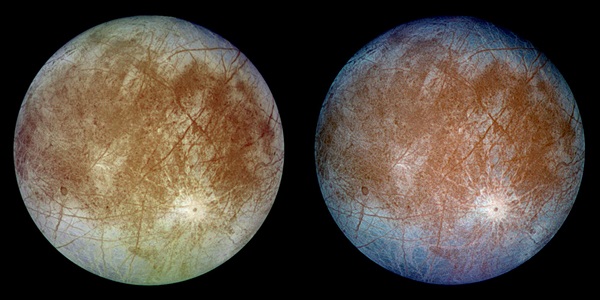

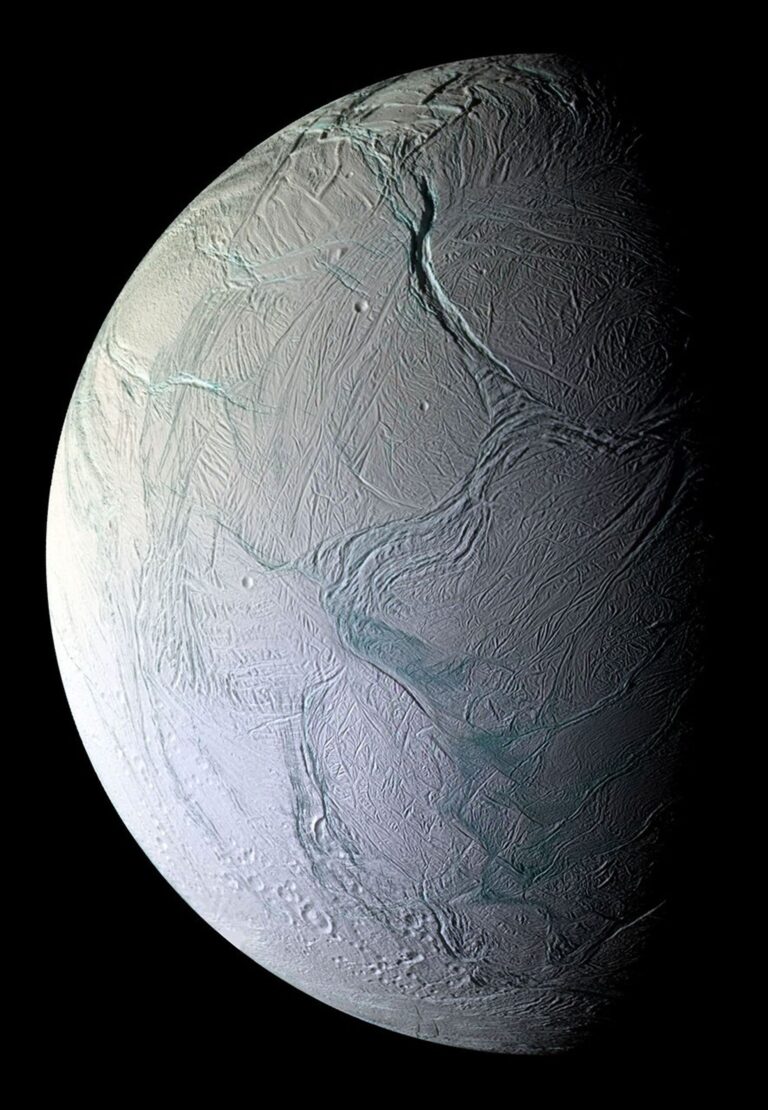

The work, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets on Monday, showed via computer models of Europa’s ice shell that a process called subduction, in which one tectonic plate meets and slides beneath another, is possible on the moon. The models’ results fall in line with prior work showing that regions of Europa’s surface appear to be expanding, making them appear much like mid-oceanic ridges on Earth and also suggesting that plate tectonics is at work.

“What we show is that under reasonable assumptions for conditions on Europa, subduction could be happening there as well, which is really exciting,” said lead author Brandon Johnson of Brown University in a press release. It’s so exciting, he continued, because “If indeed there’s life in that ocean, subduction offers a way to supply the nutrients it would need.”

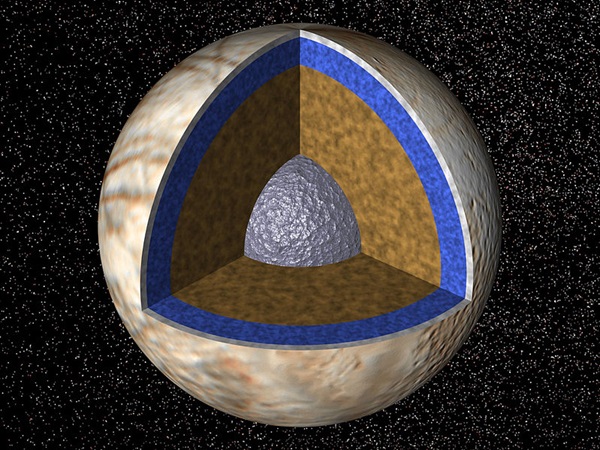

When subduction happens on Earth, it’s because the crust is cooler and denser than the mantle. This causes plates to sink, sometimes deep within the mantle. On Earth, the crust and mantle are composed of rock, but on Europa, the moon’s shell is made of ice. Though there is evidence that Europa’s shell is bi-layered, with the coldest and densest ice on top, any ice plate that began to sink beneath another would warm up, fall in density, and stop, leaving scientists to wonder whether subduction was really possible.

“Adding salt to an ice slab would be like adding little weights to it because salt is denser than ice. So rather than temperature, we show that differences in the salt content of the ice could enable subduction to happen on Europa,” Johnson said.

But is that explanation likely? As it turns out, yes — scientists have observed evidence on the moon’s surface of upwelling water from below the ice shell, much like magma wells up from vents on Earth. That upwelling water should leave behind a high concentration of salts. Furthermore, potential cryovolcanism could literally spray the surface with added salts.