Jupiter data downlink in progress

Although New Horizons is less than 2 weeks past its closest approach to Jupiter, we’re already about 14 million miles (22 million kilometers) from the giant planet and 500 million miles (800 million km) from the Sun! The spacecraft took its final images and spectra of Jupiter-system targets last week. Henceforth, the only observations New Horizons will make of the Jupiter system are measurements of the planet’s magnetotail using our PEPSSI and SWAP charged-particle spectrometers. Beginning in April, we’ll also study interplanetary dust with Venetia — our Student Dust Counter.

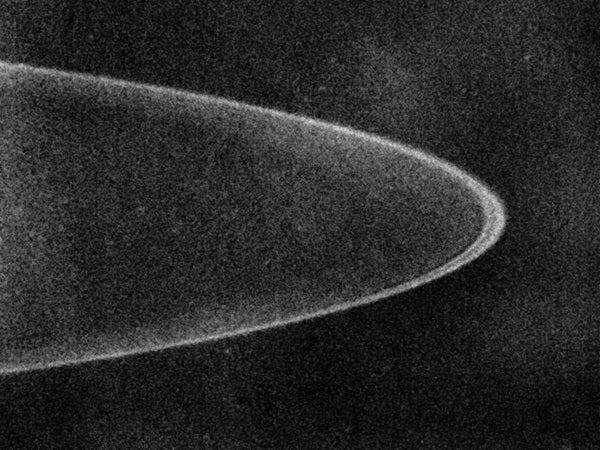

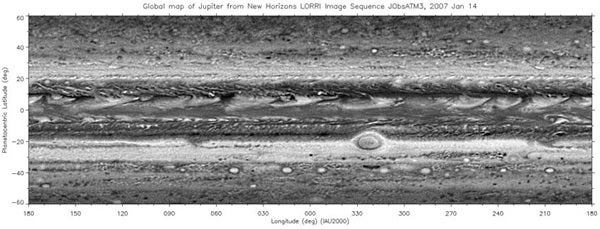

Last Wednesday, the spacecraft began downlinking its storehouse of more than 36 gigabits of Jupiter data. From now through May, we expect to receive 6 to 8 hours of Deep Space Network time, virtually every day, for this data playback. Already, we’ve received a variety of Alice ultraviolet and Ralph infrared spectra, as well as LORRI images of Jupiter, its tenuous ring system, and Io. Every week for the next 8 to 10 weeks, you can expect to see one or more image releases on our mission web site.

The next big event on the spacecraft occurs March 21. That’s the day we fire our maneuvering jets to spin up the spacecraft like a top. After that, New Horizons will rotate stably at 5 RPMs, saving fuel now that all the pointing operations associated with the Jupiter flyby are complete. This is the way we flew most of the cruise to Jupiter, and it’s how we’ll fly most of the way to Pluto.

Although I won’t be writing weekly blogs now that Jupiter is well behind us, you can look forward to a late April or early May press conference, in which we’ll show off some of the most exciting data we’ve received. Meanwhile, keep on exploring, as we do!

Outbound

The intensive phase of Jupiter encounter operations is winding down, but it’s not over yet. Early this week, we still have Radio Science Experiment (REX) and Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) calibrations using targets in the Jupiter system, and some imaging of two small jovian moons, Elara and Himalia, to better determine their shapes and how they reflect light at different phases. After that, the encounter becomes almost entirely magnetotail exploration using the Solar Wind around Pluto (SWAP), Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI), and Venetia (the Student Dust Counter) instruments. This final phase of the encounter lasts until mid-June.

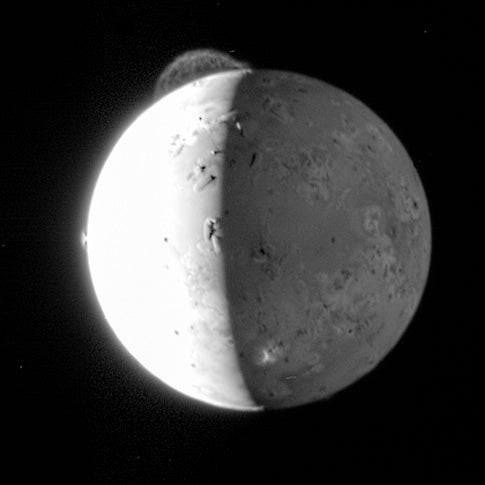

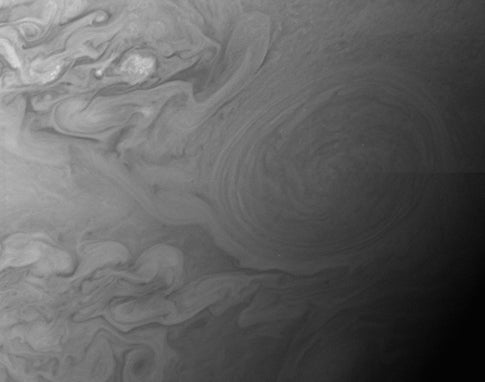

In the past week, we conducted more than 98 separate observing sequences, entailing several hundred observations. I am pretty sure that if you’re reading this, you’ve seen some or all of the handful of images we released in the past week — such as the beautiful LORRI images of Jupiter’s Little Red Spot and Io’s Tvashtar volcano. You can see more images here.

Well, those data represent less than 1/1000 of what we still have to send down. These will include color images, more high-resolution shots, ultraviolet and infrared spectra galore, and plasma data. So, while the tip of the iceberg is now on the ground to whet our appetites, we won’t have the entire dataset (36 gigabits!) on the ground until at least late April. Don’t despair — we will begin downlinking operations March 7, and will be sending back a few gigabits each week. You can expect to see other dataset releases coming from New Horizons nearly every week throughout March and April.

As things settle down on the spacecraft, we’ve already begun planning the last portions of our instrument-payload commissioning tests — things we put off until after the rush of the Jupiter encounter. We’re also planning some hibernation-mode testing for April and a tiny (jogging speed) course correction for May 23rd to trim up our trajectory.

Well, that’s it for now, but I’ll be back with more news and views soon. Meanwhile, keep on exploring, as we do!

One day beyond Zeus

The eighth mission to the fifth planet has reached its crescendo — Jupiter, my friends, is now in the rearview mirror!

Just yesterday, New Horizons passed closest approach, sealing the deal on our gravity assist and setting us up for an encounter with the Pluto system in mid-July 2015.

With that news came an impromptu press conference, a series of television and radio interviews, an evening lecture by mission scientist John Spencer to a crowd of hundreds, and then more interviews. It reminded me of the attention we got during the launch campaign. That proved fitting in a way, because in a real sense, yesterday’s flyby completed our January 2006 launch — with Jupiter serving as the fourth stage that “fired” 13 months after the three stages of our Atlas V rocket. Now, we’re truly on the Pluto leg of our journey, having gained the speed boost and turn required for our date with scientific destiny, nine summers hence.

Onward now, to the Kuiper Belt. This third zone of our planetary system serves as an ancient relic of planetary formation, and a scientific wonderland at the frontier of humankind’s home solar system!

I’ll be back in a few days with more news about the scientific observations New Horizons is making — and 4 more jam-packed days of Jupiter system observations await before we settle down for the long jovian exploration traverse.

But that’s it for now. I’ll be back with more news and views soon. Keep exploring, as we do!

Range to Jupiter: 0.03 astronomical unit (2.8 million miles; 4.5 million kilometers)

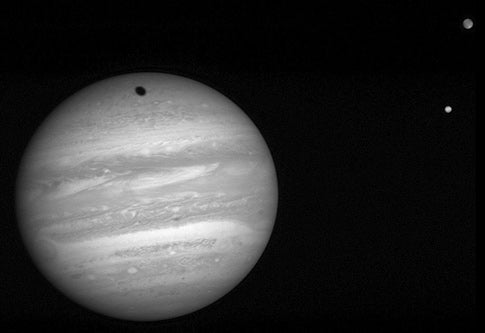

We’re in the thick of it at Jupiter now! Since early Saturday, the 24th, New Horizons has been executing its Jupiter close approach sequence. This sequence contains 15 to 20 observations per day — almost 10 times what we were doing just a week earlier.

Here on the ground, we aren’t seeing much science data yet. But the engineering data we’re getting shows the encounter is progressing according to plan (nominally, as we in the space business like to say), and the various observations are coming off right on schedule.

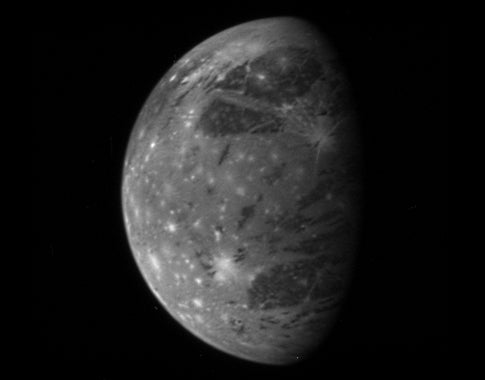

What’s up next? Well today (Monday the 26th), we are studying the atmospheric composition and structure of Io and Callisto, mapping the surface compositions of Ganymede and Europa, imaging Io’s volcanic plumes, searching for moonlets embedded in Jupiter’s rings, obtaining ring images to study how its dust particles behave depending on phase angle, and taking high-resolution images of the Little Red Spot on Jupiter itself. We’re also studying Jupiter’s magnetosphere continuously and sending home 8 hours of downlink data. We reach closest approach late tomorrow, but not before we make twice as many observations as we did today!

Before I close for today, I’ve been asked recently to say something about what became of the now derelict Boeing STAR-48 upper stage, which boosted us onto our Jupiter trajectory. Well, the last anyone saw it was on launch day. As a result, we don’t know its trajectory nearly as well as we do the path of New Horizons. We do know, however, that the upper stage will make its closest approach to Jupiter Tuesday (the 27th), approximately 6 hours before New Horizons does.

Moreover, we know the upper stage is headed to an aim point almost 300,000 miles (half a million km) farther from Jupiter than New Horizons. As a result of these “errors” in its trajectory, it will miss Pluto in 2015 by a wide berth — about 120 million miles (200 million km) — nearly as far as the distance between the Sun and Mars!

OK, that’s it for now. I’ll be back with more news and views later this week. Keep exploring, as we do!

Range to Jupiter: 0.08 astronomical unit (7.4 million miles; 12 million kilometers)

We’re now less than a week away from Jupiter closest approach! One aspect of our flyby I have not yet noted involves the broad campaign to coordinate our observations of Jupiter with those on Earth and in space. As New Horizons approaches Jupiter, telescopes on terra firma, in Earth orbit, and even far across the solar system are viewing the giant planet to give us the big-picture context while New Horizons provides the fine details.

Examples of the instruments we have enlisted to this cause include: a network of amateur telescopes imaging Jupiter; NASA’s 3-meter Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) and NASA’s 10-meter Keck telescopes on Mauna Kea, Hawaii; and the Hubble Space Telescope (HST); Chandra X-ray Observatory (CXO); and Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE) satellites operating in Earth orbit. These various facilities will image and take spectra of Jupiter’s atmosphere and aurora, the Io plasma torus, and Io itself during the next 2 weeks.

In addition, the Alice ultraviolet spectrometer (UVS) on the European Space Agency’s Rosetta comet orbiter mission will observe the Io plasma torus from its ringside seat near Mars beginning next week. (Rosetta flies by Mars February 25 for a gravity assist of its own.)

Rosetta’s Alice, a sister of the Alice UVS on New Horizons, will monitor the Io plasma torus and Jupiter’s auroral emissions during March and April as New Horizons flies down Jupiter’s magnetotail. Why? The Alice instrument aboard New Horizons can’t perform these tasks because they would involve looking almost directly back toward the blinding Sun. Rosetta’s Alice instrument can achieve the same goal because Jupiter lies deep in the night sky as seen from Mars. Pretty sweet, huh?

As we gear up for the onslaught of observations New Horizons will make, my team at New Horizons thanks all of the ground-based and space-based observing teams, whose vital supporting observations will strengthen and deepen the value of our Jupiter flyby.

I’ll be back with more news and views in a few days. Keep exploring!

Range to Jupiter: 0.11 astronomical unit (10 million miles; 16 million km)

As I write this on the weekend, New Horizons is just 10 days from closest approach to Jupiter. If you’ve been monitoring our web site, you’ve likely noticed that the spacecraft is already accelerating because of Jupiter’s gravity. Although the effect hasn’t amounted to much yet, it will build dramatically in the coming days. By the middle of next week, the giant planet will be giving us a boost of approximately 9,000 mph (14,500 km/h). That’s half the speed of a space shuttle in Earth orbit — essentially for free!

Meanwhile, our spacecraft and payload continue to perform well. As is the case most weeks, no unexpected events occurred. Further, all the planned Jupiter observations were conducted just as planned. But most important, our tracking data show us right on course to the “Pluto keyhole” — the spot we have to hit at Jupiter to remain on target for Pluto.

This is the final week of the low-intensity observation period before the Jupiter onslaught begins Saturday, February 24. The coming week’s highlight for me will be a pair of observations by our Alice ultraviolet spectrometer (UVS), which on Thursday will observe Jupiter as it occults a background star, probing the temperature and density of the planet’s upper atmosphere, and testing a technique we’ll use to probe Pluto’s atmosphere in 2015.

Next week, the pace of operations reaches its crescendo near Jupiter, with some 15 to 20 observation sequences each day. We’ll observe Jupiter itself, its rings, its moons, and its magnetosphere. Also next week, the New Horizons Science Team will meet to plan the data analysis activities to come, and to begin (already!) planning for our Pluto encounter. Sure, the Pluto system lies 8 years in the future, but earlier tonight I was watching a movie on TV from 1999, and I realized that seems like yesterday. So onward we go. It may be a long haul, but it will be worth it when we get to the frontier that is the Kuiper Belt!

I’ll be back with more news and views next week. Keep exploring.

Range to Jupiter: 0.17 astronomical unit (16 million miles; 25 million km)

If you take a look at our “Where is New Horizons?” web page, which displays the spacecraft’s trajectory status, you’ll see we’re right on Jupiter’s doorstep. And it’s true. Jupiter already appears one-third of a degree across — just a little smaller than the Full Moon as seen from Earth — and growing every day. By early next week, Jupiter will be almost two-thirds of a degree across. And by closest approach just over 2 weeks from now, Jupiter will loom 3.6° across — about the size of a golf ball held at arm’s length. That may not sound like much, but it beats the size of anything we have or will pass on the way to Pluto, except Earth itself in the first 2 hours of the flight. (FYI: We passed the Moon at a range of about 114,000 miles [184,000 km], making its maximum size some 9 hours after launch just a tad under 1.1° across.)

Of course, that doesn’t mean we aren’t busy. We’re planning a full science-team meeting for closest approach; and we’re completing the review process of the closest-approach command loads after running them on NHOPS — our spacecraft simulator. We’re also putting in place our entire March through June operations plan, which will include observations of Jupiter’s magnetotail, a trajectory course correction, a practice run at spacecraft hibernation, and various other spacecraft and instrument tests to complete the final bits of commissioning before we enter hibernation this summer. I’ll be back with more news next week.

Range to Jupiter: 0.25 astronomical unit (23 million miles;

37 million km)

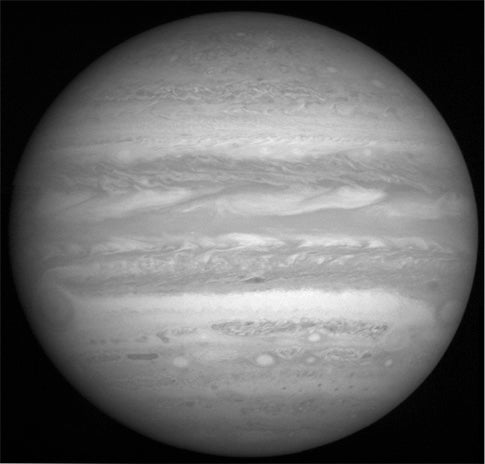

Last week, we passed an interesting milestone on our approach to Jupiter: We’re now officially inside Jupiter’s outermost satellite system. This occurred when New Horizons passed inside the outer part of the orbit of S/2003 J2, the moon that ranges farthest from the giant planet. In just a few days, we’ll reach another interesting milestone, when images from our high-resolution imager (LORRI) will exceed for the first time the best resolution the Hubble Space Telescope currently can deliver.

Pretty cool? You bet, and these kinds of measurements will only get better as our distance from Jupiter shrinks from about 25 million to 1.4 million miles (40 million to 2.3 million kilometers) in the next 3 weeks! In fact, dramatic improvements are in store for all the instruments participating in Jupiter encounter science.

As just one example, next Saturday (February 10), LORRI will take its best full-disk portrait of Jupiter, just before the giant planet fills the camera’s field of view. Wait till you see that mouthwatering image, astronomy fans! It’s time to get back to work, but I’ll be back with more news next week.

Range to Jupiter: 0.32 astronomical unit (30 million miles;

48 million km)

Welcome to a blog I’m authoring for Astronomy.com as New Horizons approaches Jupiter for a gravity-assist flyby, which will send us on toward the Pluto system. As I write this first entry, we’re just 29 days from closest approach — February 28. (Actually, in the United States, closest approach occurs late on the 27th, but it’s officially the 28th because we track all events in Universal Time.)

Our spacecraft is in good health and flying right down the proper trajectory corridor. As of this writing, we’ve traversed 93 percent of the distance from our launch point to our Jupiter aim point, and things are getting exciting!

And our two space plasma instruments, SWAP and PEPSSI, are already seeing telltale signatures of Jupiter’s gigantic magnetosphere, which we’ll be penetrating in a couple of weeks or so. With these results already back on Earth, our appetite has been whetted for the juicier data to come as we get ever closer.

In the coming week, New Horizons primarily will be making round-the-clock plasma observations using SWAP and PEPSSI, but we also will be calibrating our main imager, called Ralph, and our radio science instrument, REX, using Jupiter as a source. These kinds of observations will continue until mid-February, when our range to Jupiter will be less than half what it is now, and when the intensity and diversity of scientific observations will pick up dramatically.

I’ll be back next week with an update on our progress, and a look at some of the data we’re receiving.