In October 1995, after decades of serious effort, astronomers announced the first discovery of a planet orbiting a Sun-like star. Until then, the few planets known to exist beyond the solar system accompanied pulsars, the collapsed remnants of burnt-out stars, and had revealed themselves through glitches in the precise timing of the pulsars’ radio emission. Because these strange cinders hardly resembled the Sun, the discovery in 1995 finally reassured astronomers that our solar system indeed has relatives — perhaps even near-twins — in the Milky Way.

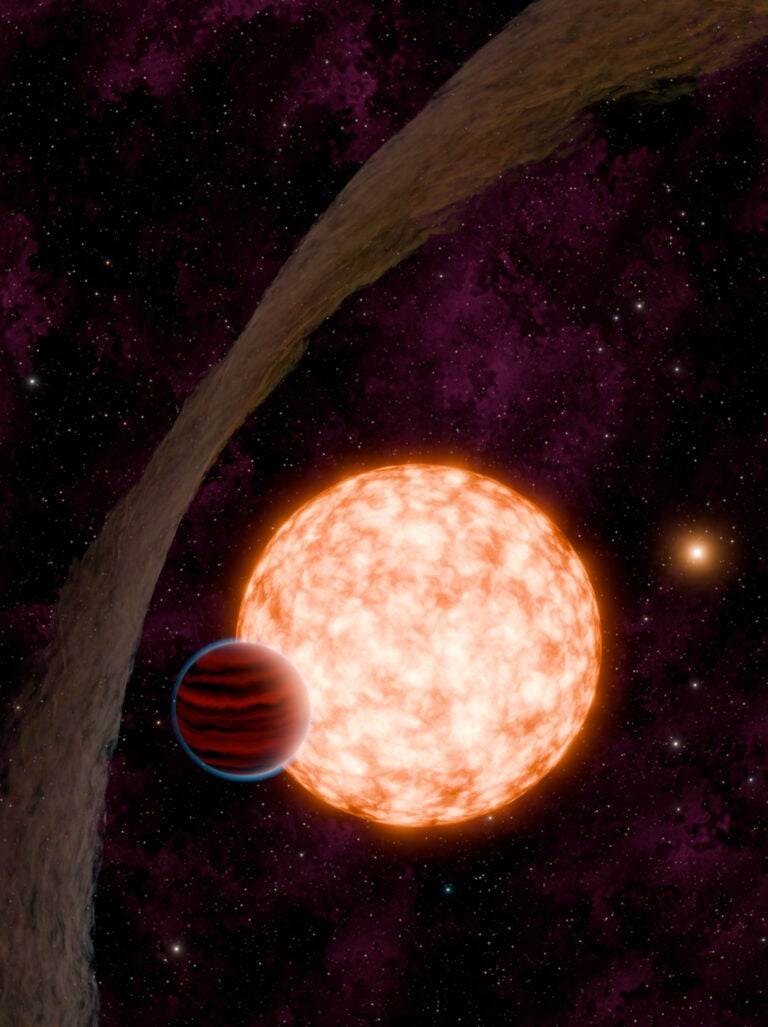

However, the first exoplanet, and five more that followed in the first half of 1996, qualified only as distant cousins. Because the technique that revealed them could find only massive planets, these exoplanets had masses comparable to Jupiter’s. But instead of circling their stars at separations comparable to the Jupiter-Sun distance, four of them had orbits far smaller than Mercury’s, and none came close to the size of Jupiter’s. Until then, using the solar system as a prototype, all models of how planets form had explained that small, rocky planets should develop close to their stars. Likewise, much larger, mostly gaseous planets would form farther out where they could amass great amounts of gas away from the star’s heat.

These first discoveries prompted theorists to spring into action. They produced models of gas giants that are born far from their stars, then migrate inward through gravitational interaction with the disk of material that formed the planets.

From the first discovery of planets beyond our Sun, the notion of our solar system as prototypical was wiped away. And the surprises have only continued.

A rich tapestry

Today, the first six exoplanets provide 0.1 percent of the entries in the catalogs maintained by NASA and the European Space Agency. Astronomers have found the great majority of these planets with just two different discovery methods, while a handful of other techniques have produced an additional minority. Their successes verify and emphasize an overarching result: Exoplanets exist in large numbers and display an amazing variety in their diameters, masses, densities, and compositions, as well as in the sizes and eccentricities of their orbits. This wealth of exoplanet riches underscores the danger, so clear in hindsight, of using a single example of a phenomenon to reach a general conclusion. There are many ways, it turns out, to make a planetary system. The now-5,000-plus discoveries show that the most common type of exoplanet doesn’t exist in our solar system at all.

Instead, the title of “most abundant” belongs to the class of super-Earths or sub-Neptunes, with masses between Earth’s and Neptune’s. Models of these planets typically envision solid cores of various sizes, surrounded either by varying amounts of hydrogen and helium (similar to jovian planets with larger cores) or by large amounts of water and thinner atmospheres. Those not much more massive than Earth may consist almost entirely of rock and metal.

Astronomers owe their increasingly productive and provocative flow of exoplanet knowledge to their use of ever more sensitive instruments. Some of these obtain data from telescopes on Earth, while others depend on spaceborne observatories. The latter includes both multipurpose facilities, such as the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), and dedicated spacecraft, most notably the European Space Agency’s CoRoT, which operated from 2006 to 2013; NASA’s Kepler space telescope, which worked from 2009 through 2018; and its successor, NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS).

Because stars typically outshine their planets’ weak reflected light by factors close to a billion or more, astronomers’ most successful techniques for detecting exoplanets look to their stars. With increasingly precise measurements, they search either for tiny variations in a star’s motion in response to a planet’s gravitational force, or for minuscule changes in a star’s brightness that occur when a planet passes in front of it. These two techniques, the radial velocity and transit methods, respectively, have revealed 93 percent of all verified exoplanets.

Discovery by radial velocity

Radial velocity refers to a star’s motion toward or away from us along our line of sight. For more than a century, astronomers have examined the spectra from stars, comparing observed wavelengths with laboratory values produced by known atoms and molecules at rest to reveal the composition as well as motion of stars.

Improvements in instruments and techniques now allow astronomers to measure these velocities to an accuracy close to a meter (a few feet) per second, a slow amble for a human. Observations that show repetitive, sinusoidal (up-and-down) deviations in a star’s radial velocity indicate the presence of a planet, tugging the star back and forth as it orbits.

Radial velocity observations yield a surprising wealth of information about unseen planets. The time from one tug to the next is related to the planet’s orbital period, and any deviations from a pure sine wave reveal the eccentricity of the orbit.

Because astronomers know the mass of the star (from their analysis of its spectrum), the planet’s orbital period allows the calculation of the size of the planet’s orbit, while the size of the up-and-down changes in the star’s radial velocity reveals the planet’s mass. Massive planets close to their stars produce the biggest, easiest-to-find signals — hence, those early massive exoplanet discoveries. One more parameter emerges from the type of star and the planet’s distance: the planet’s surface temperature in the absence of an atmosphere. Modelers can provide many more options for how that temperature could vary with different feasible atmospheres.

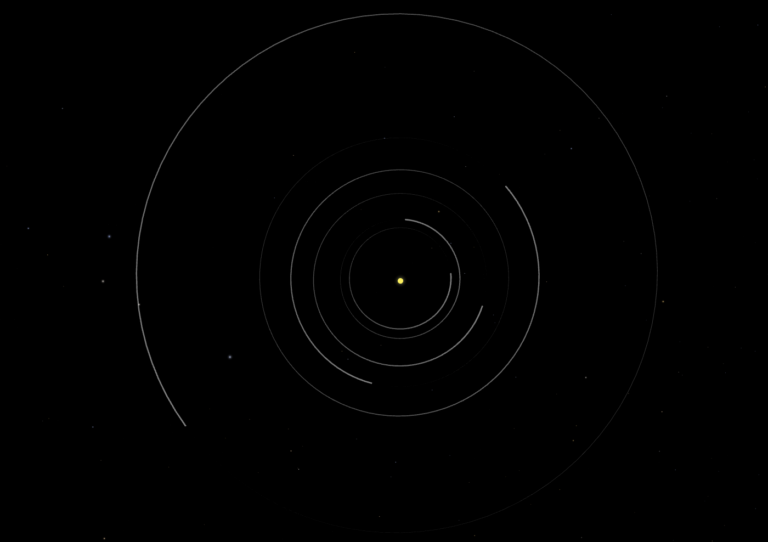

The radial velocity measurement technique can even discover multiple planets around a given star. In a multiple system, each planet imposes its own sinusoidal pattern on the star’s radial velocity, adding to a seemingly tangled, superimposed mess. However, astronomers can disentangle it with proper analysis. The current record-holder belongs to a six-planet system, and we may reasonably expect even larger systems to emerge from this approach.

By now, radial velocity variations have revealed more than a thousand exoplanets, making it the second most successful discovery method. Observational programs across the globe continue to search for planets with this method, pushing the limits of detection to find ever more elusive worlds — those with smaller masses, orbiting farther away from their stars — planets like the ones we know in our own solar system.

Discovery by transit

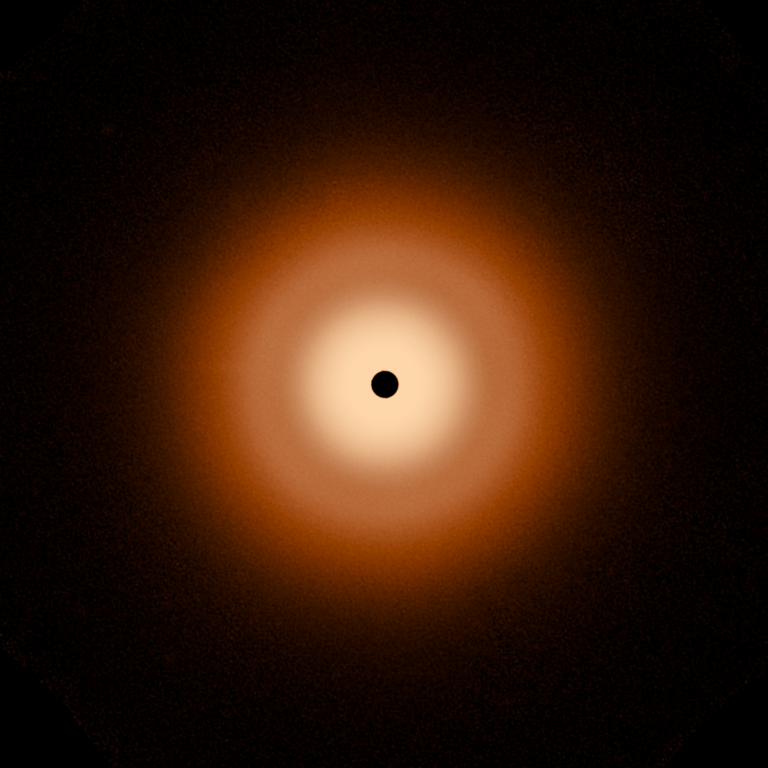

The transit method is far and away the most successful way to discover exoplanets. Transit surveys monitor stars’ brightnesses almost continuously, searching for minuscule dips that arise if a planet passes directly in front of the star, which recur regularly as a planet completes each orbit. This will occur only if the planet’s orbital plane coincides almost exactly with our line of sight.

Because most exoplanet orbits lack this fortunate alignment, astronomers know full well that even their best instruments cannot find the majority of exoplanets using the transit technique, although smaller orbits increase the chance of alignments that produce transits. Almost in compensation for this incompleteness, transit observations provide not only the exoplanet’s orbital period but also its size (though not its mass), because astronomers know the size of the star, revealed by its spectral characteristics.

The restless nature of Earth’s atmosphere makes spaceborne observatories much better at detecting the tiny changes due to a transit in a star’s brightness. If an extraterrestrial civilization observed transits of the Sun’s planets, they would note a dip by 1 percent when Jupiter passed in front of the Sun, and 0.01 percent when Earth made its passage (five times more frequently). By our standards, verification of an exoplanet’s existence requires at least three transit observations, so a Jupiter-sized planet in a Jupiter-sized orbit would take at least 10 years to achieve this status.

Exoplanets discovered by the transit method offer a unique additional benefit. By comparing high-resolution spectroscopic observations of the star and planet during a transit with observations of the star alone, astronomers can determine whether the exoplanet has an atmosphere. If it does, they can even sometimes deduce the composition of that atmosphere from its contribution to the total spectrum.

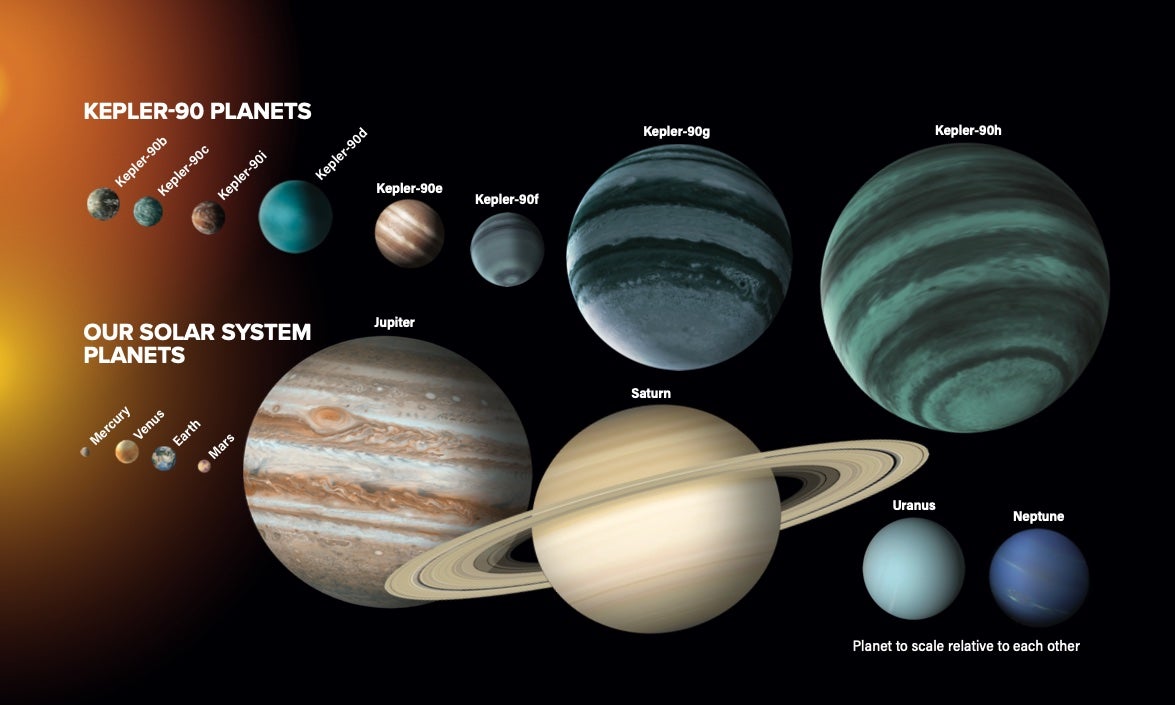

Like radial velocity results, the rhythm of the transits caused by multiple planets in a system can be disentangled to reveal the size and orbital period of each world. Astronomers have applied this technique to discover one system with seven exoplanets, and another with eight. These planets all orbit in nearly the same plane (we would not detect them all otherwise), as the Sun’s planets do. As with the radial velocity method, exoplanet detection by transits occur more readily around smaller, less luminous stars, whose planets produce larger changes in velocity and brightness. And although most of the systems with multiple planets we’ve found orbit comparatively smaller, low-mass, low-luminosity red dwarf stars, some do appear around stars more like our Sun.

Discovery by lensing

One more exoplanet discovery technique deserves attention for its impressive abilities (and its failings): gravitational lensing. As Einstein demonstrated, gravitational forces bend space, so a massive object that passes almost directly in front of a more distant source of light will change the path of light from the source, typically focusing it to produce a temporary increase in brightness. If a star’s motion happens to carry it almost across the line of sight to a more distant star, gravitational lensing will brighten the light from the farther star for a few weeks or even months, based on typical stellar velocities.

Called microlensing events, the size and duration of these “blips” in stellar brightness increase with the mass of the foreground star that produces them. And within these blips, sometimes there is a much smaller, briefer blip, lasting perhaps hours, superimposed on the overall brightness curve. The smaller blip, which can be produced by a planet in orbit, reveals the planet’s mass. Microlensing events can be observed even if the lensing star lies tens of thousands of light-years away. That distance is near or beyond the reach of the radial velocity and transit methods, most of which succeed for stars hundreds to a few thousand light-years away. Microlensing, however, has one great drawback: It is one and done. Once the foreground star has moved away from the farther star, no hope exists for a recurrence of that situation.

More discoveries coming

The ever-growing exoplanet census now includes more than 1,000 members in more than 800 planetary systems found by radial velocity observations, more than 200 discovered by microlensing effects, and some 4,300 revealed by their transits. Many more candidates await confirmation via future observations. More complex and subtle methods have added several dozen additional planets to the overall list, with 82 more planets (as of this writing) from the straightforward but highly difficult approach of direct imaging.

Future exoplanet discoveries follow a dual pathway: detection of more planets, especially with new instruments, and superior analysis of exoplanets already on the list. Today, astronomers have three primary (but nowhere near the only) instruments to discover and examine planets in the Milky Way. One more should soon join them, while a fifth, the most powerful, will — if all goes well — begin operation in 20 years or so.

The three instruments that currently return some of the biggest streams of useful data are TESS, HST, and JWST. The next on the list, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, has a scheduled launch date in mid-2027, while the fifth — with the greatest potential for exoplanet discoveries — is the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), still in development. While astronomers promoting and guiding HWO remain highly enthusiastic, commentators often note that the slow bleed of funding for NASA’s most ambitious projects casts some doubt of having the spacecraft ready for launch in the mid-2040s, as currently planned.

Within the next few years, TESS’s more than 7,200 exoplanet candidates should yield at least another 1,000 confirmed planets, as repeated transit observations verify them. Astronomers can then combine transit data with radial velocity measurements made with giant ground-based telescopes to verify and improve the accuracy of the orbital data derived from TESS’s observations. Many of TESS’s newfound worlds, as well as those discovered by other planet-finding techniques, furnish a rich field of study for JWST, and a lot of observational time with the mighty telescope has been reserved for exoplanet follow up.

Hoped-for discoveries

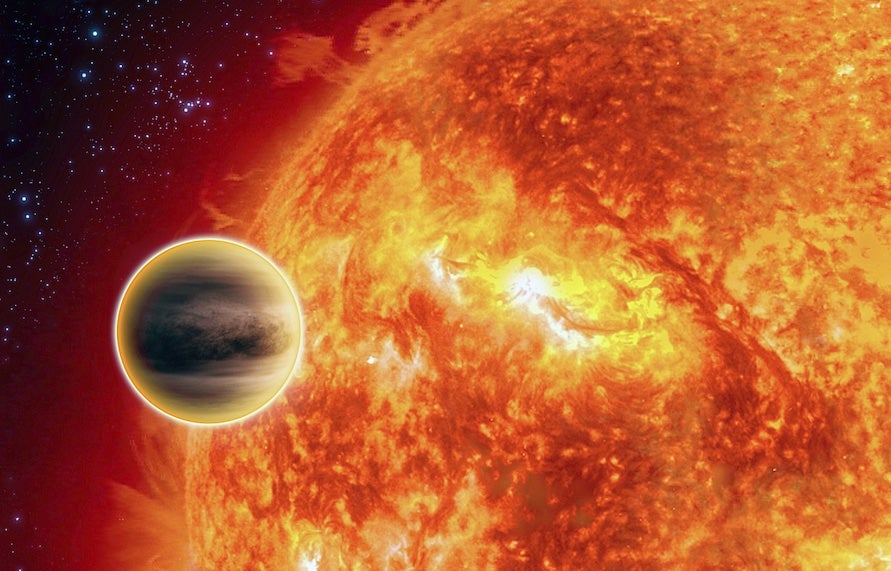

Astronomers will gain even more exoplanet observations when Roman joins JWST in orbit around Earth’s second Lagrangian point — a spot that provides orbital stability — some 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) farther from the Sun than Earth. Like HST, Roman will have a mirror 2.4 meters in diameter. Unlike HST, though, Roman will employ just two instruments: a wide-field camera and a coronagraph. The camera will observe the cosmos in infrared radiation as well as visible light, and will secure images as detailed as Hubble’s, but over a field of view 10 times wider.

Roman’s first-of-a-kind visible-light and infrared coronagraph will use a series of masks, prisms, and deformable mirrors to block the direct light from a star and feed the remaining light from the star’s surroundings into a high-contrast camera and spectrometer. This should allow the coronagraph to obtain images and spectra of planets with as little as one-hundred-millionth of their parent star’s brightness, revealing and characterizing exoplanets similar to Jupiter in diameter and orbital distance.

Jupiter-like planets have their merits, but the ultimate goal of exoplanet hunters naturally centers on securing images of Earth-like planets — those with about one-tenth Jupiter’s diameter, orbiting their stars at distances that would allow liquid water to exist on their surfaces. To achieve this goal, astronomers require a much larger instrument: HWO, with a mirror as large as the 6.5-meter mirror on JWST. And some astronomers envision one considerably larger. Although this spacecraft would investigate both solar system objects and distant galaxies, its name reflects its primary mission: to discover and study potentially habitable worlds.

To accomplish these goals, HWO would employ spectroscopy to look for biosignatures in exoplanet atmospheres, as well as direct imaging using a coronagraph. The more ambitious plans for HWO call for a sunshield, whose orbit near HWO would keep it positioned to block almost all light from the target star. The reason for such a proposal is that blocking starlight can be more complete before light enters a telescope, rather than after.

A sunshield working in tandem with HWO’s coronagraph would finally create an instrument capable of securing images of exoplanets whose reflected light, like Earth’s, falls more than a billion times below their star’s brightness. MIT professor Sara Seager, one of the leaders in the hunt for exoplanets, has set as her chief professional goal “to find another Earth.” This means a planet the size of ours, moving in a similar orbit around a Sun-like star. She has stated in a number of interviews, “As a human species, we want to find something like our own [planet],” she notes, demonstrating that astronomers experience the same emotions as the rest of us when we consider the grand variety of planets in the Milky Way.

Will this require another 20 years? If so, the 50th anniversary of the first exoplanet discoveries could mark the time when humans find Earth’s near-twin in the Milky Way.