Either the system is twice as bright as it should be or it’s much more massive than scientists have surmised. The answer matters, in part, because it could inform theories about how the supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies came to be.

“This has been a very frustrating field to work in,” said Joel Bregman, professor of astronomy at the University of Michigan. “We’ve been looking for indirect measurements that we thought would tell us something, but you’d get 10 pieces of information, and five would be on one side and five on the other. You’d think, ‘This could all be solved if I could just measure the mass directly.’”

Now, Bregman is part of an international team that has done that. They show that the black hole in the system is a fairly typical one, at least in terms of its mass. It’s a so-called stellar black hole — the kind that forms when a star up to about 200 times the size of the Sun collapses at the end of its life. This one, they discovered, is between 20 and 30 times the mass of its companion star.

“As if black holes weren’t extreme enough, this is really [an] extreme one that is shining as brightly as it possibly can. It’s figured out a way to be more luminous than we thought possible,” Bregman said.

“These findings show that our understanding of black hole accretion is incomplete and needs revision,” said Jifeng Liu from the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing.

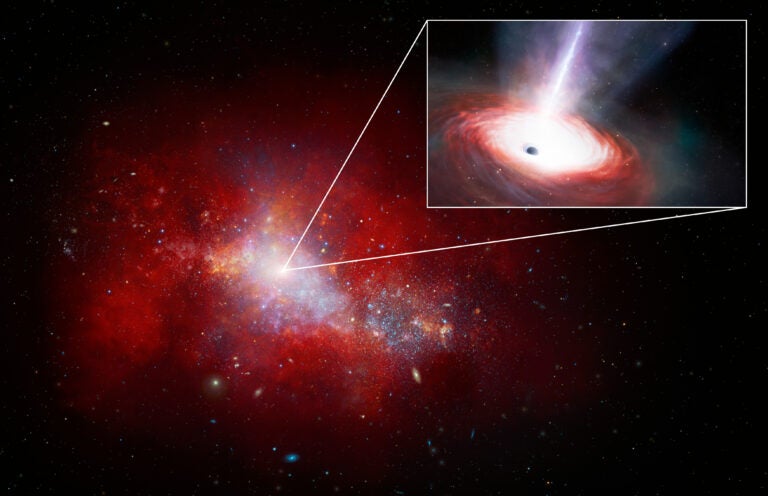

Accretion is the process of black holes consuming material, growing, and indirectly radiating. While nothing, not even light, can escape black holes, the swirling stuff falling into them emits X-rays. Astronomers study these X-rays in an effort to understand how black holes grow.

“Now that we know the mass, we can move on to figuring out why it’s so bright,” Bregman said.

Maybe it’s feeding off its companion’s stellar wind — a stream of charged particles emanating from its upper atmosphere. That mechanism was previously thought to be too inefficient, but it’s a possibility the researchers suggest. Or maybe bubbles are forming in the disk of material that’s falling in, creating additional radiation, the astronomers said.

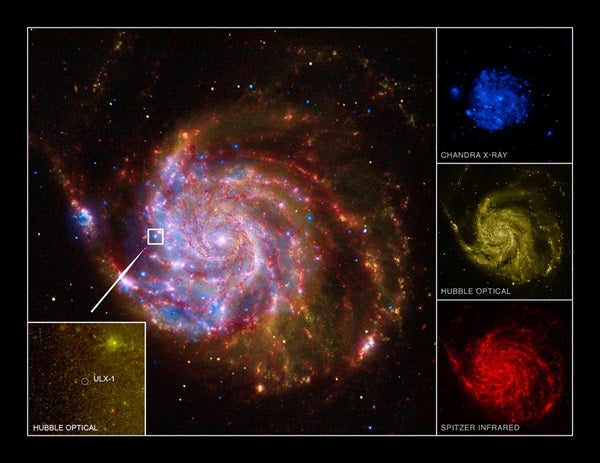

To measure the mass of this system, known as ULX-1, Liu and colleagues first looked at the system through the Gemini telescope. Then they conducted a spectroscopic analysis of the images, which involved analyzing the color of the light to figure out which elements the star in the system contained. They found that there wasn’t much hydrogen in the star. That helped them determine it’s a type known as a Wolf-Rayet. Such stars are rare, large, and hot. And they’re shrinking fast due to their strong stellar winds.

Once the researchers knew the kind of star, they could infer its mass from its brightness. That told them it was roughly 19 times the mass of the Sun.

By comparing images over three months, they were able to determine how often the star and black hole orbit each other — roughly once every eight days. Once they had all this information, they took into account the likelihood of various viewing angles and used Newton’s laws of motion to estimate the black hole mass at 20 to 30 times the mass of the Sun.

The findings also have broader astronomical implications. They mean that the search is still on for what astronomers refer to as “intermediate-mass black holes,” Liu said. Intermediate-mass black holes could be the seeds of the supermassive black holes at the core of most, if not all, galaxies. How the supermassive ones form is still an open question in astrophysics. The theory that involves coalescing an intermediate species sounds promising, but scientists have yet to find any intermediate black holes to start with. Nor do they have a strong theory to explain how the middle-weights would form.

“Our findings may turn the trend of taking ultraluminous X-ray sources as promising intermediate black hole candidates,” Liu said.