Most of the thousands of exploding stars classified as type Ia supernovae look similar, which is why astrophysicists use them as accurate cosmic distance indicators. They have shown that the expansion of the universe is accelerating under the influence of an unknown force called dark energy; yet approximately 20 type Ia supernovae look peculiar.

“They’re all a little bit odd,” said George Jordan from the University of Chicago’s Flash Center for Computational Science. Comparing odd type Ia supernovae to normal ones may permit astrophysicists to more precisely define the nature of dark energy, he noted.

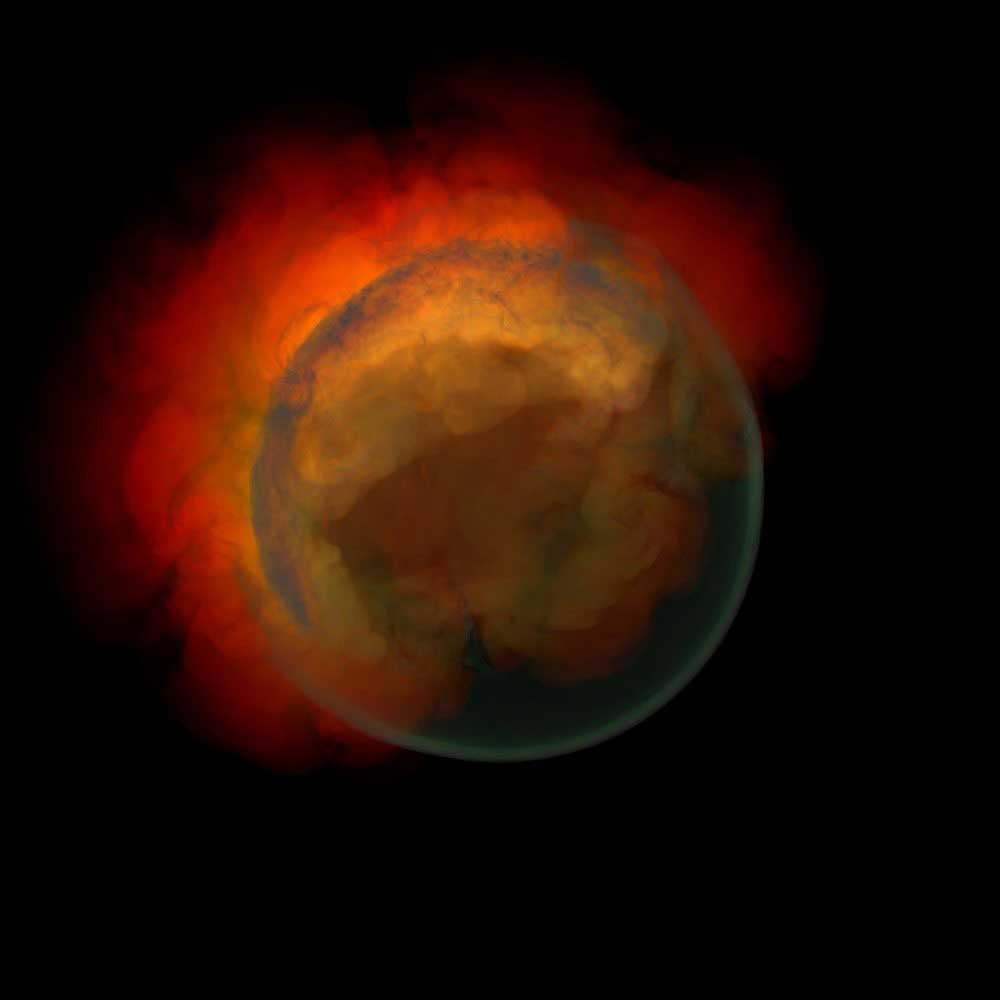

Jordan and three colleagues, including his chief collaborator on the project, Hagai Perets from Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, have found that the peculiar type Ia supernovae are probably white dwarf stars that failed to detonate. “They ignite an ordinary flame and they burn, but that isn’t followed by a triggering of a detonation wave that goes through the star,” Jordan said. These findings were based on simulations that consumed approximately 2 million central processing unit hours on Intrepid, the Blue Gene/P supercomputer at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Illinois.

The triggering of a detonation wave is exactly what happens in normal type Ia supernovae, which incinerate white dwarfs, stars that have shrunk to Earth-size after having burned most or all of their nuclear fuel. Most or all white dwarfs occur in binary systems — those that consist of two stars orbiting one another.

Faint, hard to detect

Peculiar type Ia supernovae are anywhere from 10 to 100 times fainter than normal ones, which are brighter and therefore more easily detected. Astrophysicists have estimated that they may account for approximately 15 percent of all type Ia supernovae.

The first in this class of exceptionally dim supernovae was discovered in 2002, noted Robert Fisher from the University of Massachusetts in Dartmouth. Called SN 2002cx, it is considered the most peculiar type Ia supernova ever observed.

The dimmest of the lot, however, was discovered in 2008. “If the brightness of a standard supernova could be thought of as a single 60-watt light bulb, the brightness of this 2008 supernova would be equivalent to a small fraction of a single candle or a few dozen fireflies,” Fisher said.

Flash Center scientists have been successfully simulating type Ia supernova explosions following the gravitationally confined detonation scenario for years. In this scenario, the white dwarf begins to burn near its center. This ignition point burns outward, floating toward the surface like a bubble. After it breaks the surface, a cascade of hot ash flows around the star and collides with itself on the opposite end, triggering a detonation.

“We took the normal GCD scenario and asked what would happen if we pushed this to the limits and see what happens when it breaks,” Jordan said. In the failed detonation scenario, the white dwarf experiences more ignition points that are closer to the core, which fuels more burning than in the detonation scenario.

“The extra burning causes the star to expand more, preventing it from achieving temperatures and pressures high enough to trigger detonation,” said Daniel van Rossum of the University of Chicago’s Flash Center.

No incinerated star

Instead of detonating, the white dwarf remains intact, though some of the star’s mass burns up and gets ejected from its surface. This failed detonation scenario looks quite similar to the peculiar type Ia explosions. The simulations resulted in phenomena that astronomers now can look for or have already found in their telescopic observations.

These phenomena include white dwarfs that display unusual compositions, asymmetric surface characteristics, and a kick that sends the stars flying off at speeds of hundreds of miles per second. “This was a completely new discovery,” Perets said. “No one had ever suggested that white dwarfs could be kicked at such velocities.”

Normal type Ia supernovae display a relatively uniform appearance, but the asymmetric characteristics of their peculiar cousins mean that the latter will often look much different from one another, depending on their viewing angle from Earth.

The asymmetric explosion also produces the kick, which is possibly powerful enough to release the white dwarf from the gravitational hold of any binary companion it may have had. This can produce a peculiar type of hyper-velocity white dwarf, the fastest of which might even escape the galaxy.

Smaller kicks might leave the binary system intact, but also push the white dwarf into a tight and highly elliptical orbit around its companion. Most white dwarfs orbiting close to their companions display a more circular orbit.

Typical white dwarfs have compositions of carbon and oxygen, yet some of the simulated ones that failed to detonate displayed heavy elements such as calcium, titanium, and iron. When the detonation fails to happen, much of the ejected mass falls back onto the surface of the white dwarf, where the heavy elements become synthesized.

“I had never heard of such strange white dwarfs,” Perets said. But when he conducted a literature search, he found reports of white dwarfs with properties that an irregular composition could explain. “It is quite rare that a new model brings about so many novel predictions and potentially solves several distinct, seemingly unrelated puzzles.”

Most of the thousands of exploding stars classified as type Ia supernovae look similar, which is why astrophysicists use them as accurate cosmic distance indicators. They have shown that the expansion of the universe is accelerating under the influence of an unknown force called dark energy; yet approximately 20 type Ia supernovae look peculiar.

“They’re all a little bit odd,” said George Jordan from the University of Chicago’s Flash Center for Computational Science. Comparing odd type Ia supernovae to normal ones may permit astrophysicists to more precisely define the nature of dark energy, he noted.

Jordan and three colleagues, including his chief collaborator on the project, Hagai Perets from Technion – Israel Institute of Technology, have found that the peculiar type Ia supernovae are probably white dwarf stars that failed to detonate. “They ignite an ordinary flame and they burn, but that isn’t followed by a triggering of a detonation wave that goes through the star,” Jordan said. These findings were based on simulations that consumed approximately 2 million central processing unit hours on Intrepid, the Blue Gene/P supercomputer at Argonne National Laboratory in Lemont, Illinois.

The triggering of a detonation wave is exactly what happens in normal type Ia supernovae, which incinerate white dwarfs, stars that have shrunk to Earth-size after having burned most or all of their nuclear fuel. Most or all white dwarfs occur in binary systems — those that consist of two stars orbiting one another.

Faint, hard to detect

Peculiar type Ia supernovae are anywhere from 10 to 100 times fainter than normal ones, which are brighter and therefore more easily detected. Astrophysicists have estimated that they may account for approximately 15 percent of all type Ia supernovae.

The first in this class of exceptionally dim supernovae was discovered in 2002, noted Robert Fisher from the University of Massachusetts in Dartmouth. Called SN 2002cx, it is considered the most peculiar type Ia supernova ever observed.

The dimmest of the lot, however, was discovered in 2008. “If the brightness of a standard supernova could be thought of as a single 60-watt light bulb, the brightness of this 2008 supernova would be equivalent to a small fraction of a single candle or a few dozen fireflies,” Fisher said.

Flash Center scientists have been successfully simulating type Ia supernova explosions following the gravitationally confined detonation scenario for years. In this scenario, the white dwarf begins to burn near its center. This ignition point burns outward, floating toward the surface like a bubble. After it breaks the surface, a cascade of hot ash flows around the star and collides with itself on the opposite end, triggering a detonation.

“We took the normal GCD scenario and asked what would happen if we pushed this to the limits and see what happens when it breaks,” Jordan said. In the failed detonation scenario, the white dwarf experiences more ignition points that are closer to the core, which fuels more burning than in the detonation scenario.

“The extra burning causes the star to expand more, preventing it from achieving temperatures and pressures high enough to trigger detonation,” said Daniel van Rossum of the University of Chicago’s Flash Center.

No incinerated star

Instead of detonating, the white dwarf remains intact, though some of the star’s mass burns up and gets ejected from its surface. This failed detonation scenario looks quite similar to the peculiar type Ia explosions. The simulations resulted in phenomena that astronomers now can look for or have already found in their telescopic observations.

These phenomena include white dwarfs that display unusual compositions, asymmetric surface characteristics, and a kick that sends the stars flying off at speeds of hundreds of miles per second. “This was a completely new discovery,” Perets said. “No one had ever suggested that white dwarfs could be kicked at such velocities.”

Normal type Ia supernovae display a relatively uniform appearance, but the asymmetric characteristics of their peculiar cousins mean that the latter will often look much different from one another, depending on their viewing angle from Earth.

The asymmetric explosion also produces the kick, which is possibly powerful enough to release the white dwarf from the gravitational hold of any binary companion it may have had. This can produce a peculiar type of hyper-velocity white dwarf, the fastest of which might even escape the galaxy.

Smaller kicks might leave the binary system intact, but also push the white dwarf into a tight and highly elliptical orbit around its companion. Most white dwarfs orbiting close to their companions display a more circular orbit.

Typical white dwarfs have compositions of carbon and oxygen, yet some of the simulated ones that failed to detonate displayed heavy elements such as calcium, titanium, and iron. When the detonation fails to happen, much of the ejected mass falls back onto the surface of the white dwarf, where the heavy elements become synthesized.

“I had never heard of such strange white dwarfs,” Perets said. But when he conducted a literature search, he found reports of white dwarfs with properties that an irregular composition could explain. “It is quite rare that a new model brings about so many novel predictions and potentially solves several distinct, seemingly unrelated puzzles.”