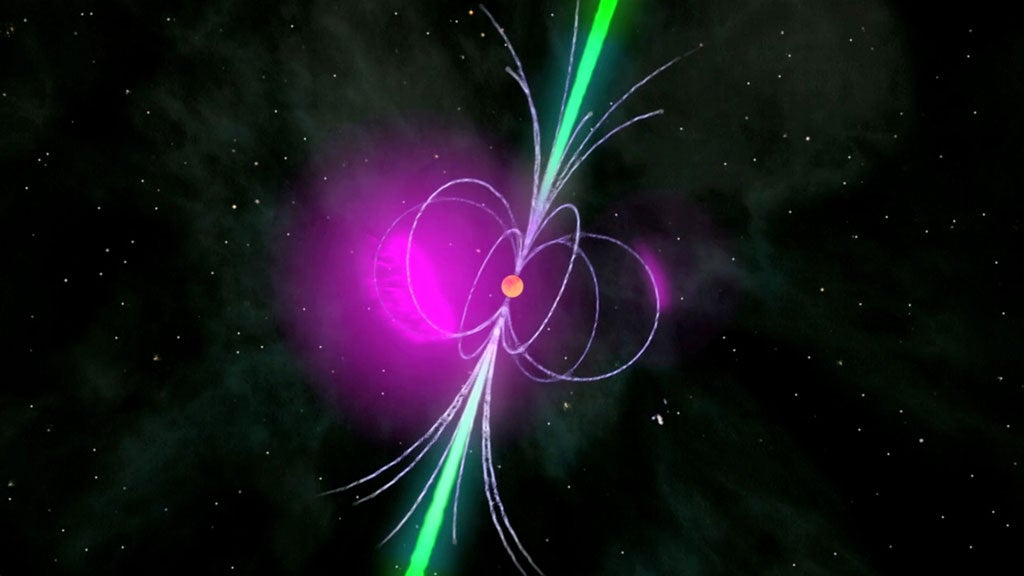

When the cores of massive stars run out of nuclear fuel, they collapse catastrophically, a phenomenon known as a supernova. This spectacular event marks the birth of a neutron star: a ball of neutrons, a single giant atomic nucleus with a radius of about 6-10 miles (10-16 kilometers) and about half a million times the Earth’s mass. A pulsar is a rapidly rotating neutron star for which we can detect pulsations (normally at radio, but now also at gamma-ray wavelengths), modulated by the rotation of the object — like a lighthouse. Ordinary pulsars have rotation periods between 16 milliseconds and 8 seconds. Even faster rotating are the so-called millisecond pulsars (MSPs), which can have rotation periods as fast as 1.4 milliseconds — corresponding to 43,000 rotations per minute. They are thought to have been spun up by accretion of matter from a companion star, a theory that is supported by the observation that roughly 80 percent of MSPs are found in binary systems.

MSPs possess extraordinary long-term rotational stability, which is in some cases similar to those of the best atomic clocks on Earth. They are basically giant flywheels in space where nothing disturbs their rotation. They are being used to test Einstein’s general theory of relativity, search for gravitational waves, and study the properties of the super-dense matter at their center.

“We have discovered more than 100 of these objects in globular clusters with radio telescopes,” said Freire. “Thanks to the sensitivity of the Large Area Telescope on the Fermi satellite, we have been able, for the first time, to see one of them in gamma rays.”

Globular clusters are ancient swarms of hundreds of thousands of stars bound together by their mutual gravity. They produce many binary systems of the kind that lead to the formation of millisecond pulsars. One of these clusters is NGC 6624 in Sagittarius. At a distance of about 27,000 light-years, it is in the proximity of the galactic center. A total of six pulsars have been discovered in this globular cluster to date, three of these to be announced soon. The first pulsar found in NGC 6624 was J1823-3021A. With a rotation period of 5.44 milliseconds (11,000 rotations/minute), it is the most luminous radio pulsar found in a globular cluster to date. It has been timed since its discovery in 1990 with several large radio telescopes, in particular with the Lovell Telescope of the University of Manchester/England and with the radio telescope at Nançay/France.

“To our surprise, we found the pulsar to be extremely bright in gamma rays, as well,” said Damien Parent from the Center for Earth Observing and Space Research. “Millisecond pulsars were not supposed to be that bright. This implies an unexpectedly high magnetic field for such a fast pulsar.”

“This challenges our current theories for the formation of such objects,” saud Michael Kramer from MPIfR. “We are currently investigating a number of possibilities. Nature might even be forming millisecond pulsars in a way we have not anticipated.”

“Whichever way these anomalous pulsars are formed, one thing appears to be clear,” said Freire. “At least in globular clusters, they are so young that they are probably forming at rates comparable to the large known population of normal millisecond pulsars.”

When the cores of massive stars run out of nuclear fuel, they collapse catastrophically, a phenomenon known as a supernova. This spectacular event marks the birth of a neutron star: a ball of neutrons, a single giant atomic nucleus with a radius of about 6-10 miles (10-16 kilometers) and about half a million times the Earth’s mass. A pulsar is a rapidly rotating neutron star for which we can detect pulsations (normally at radio, but now also at gamma-ray wavelengths), modulated by the rotation of the object — like a lighthouse. Ordinary pulsars have rotation periods between 16 milliseconds and 8 seconds. Even faster rotating are the so-called millisecond pulsars (MSPs), which can have rotation periods as fast as 1.4 milliseconds — corresponding to 43,000 rotations per minute. They are thought to have been spun up by accretion of matter from a companion star, a theory that is supported by the observation that roughly 80 percent of MSPs are found in binary systems.

MSPs possess extraordinary long-term rotational stability, which is in some cases similar to those of the best atomic clocks on Earth. They are basically giant flywheels in space where nothing disturbs their rotation. They are being used to test Einstein’s general theory of relativity, search for gravitational waves, and study the properties of the super-dense matter at their center.

“We have discovered more than 100 of these objects in globular clusters with radio telescopes,” said Freire. “Thanks to the sensitivity of the Large Area Telescope on the Fermi satellite, we have been able, for the first time, to see one of them in gamma rays.”

Globular clusters are ancient swarms of hundreds of thousands of stars bound together by their mutual gravity. They produce many binary systems of the kind that lead to the formation of millisecond pulsars. One of these clusters is NGC 6624 in Sagittarius. At a distance of about 27,000 light-years, it is in the proximity of the galactic center. A total of six pulsars have been discovered in this globular cluster to date, three of these to be announced soon. The first pulsar found in NGC 6624 was J1823-3021A. With a rotation period of 5.44 milliseconds (11,000 rotations/minute), it is the most luminous radio pulsar found in a globular cluster to date. It has been timed since its discovery in 1990 with several large radio telescopes, in particular with the Lovell Telescope of the University of Manchester/England and with the radio telescope at Nançay/France.

“To our surprise, we found the pulsar to be extremely bright in gamma rays, as well,” said Damien Parent from the Center for Earth Observing and Space Research. “Millisecond pulsars were not supposed to be that bright. This implies an unexpectedly high magnetic field for such a fast pulsar.”

“This challenges our current theories for the formation of such objects,” saud Michael Kramer from MPIfR. “We are currently investigating a number of possibilities. Nature might even be forming millisecond pulsars in a way we have not anticipated.”

“Whichever way these anomalous pulsars are formed, one thing appears to be clear,” said Freire. “At least in globular clusters, they are so young that they are probably forming at rates comparable to the large known population of normal millisecond pulsars.”