Key Takeaways:

“Scientists have been trying to find the sources of high-energy cosmic rays since their discovery a century ago,” said Elizabeth Hays from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “Now, we have conclusive proof supernova remnants, long the prime suspects, really do accelerate cosmic rays to incredible speeds.”

Cosmic rays are subatomic particles that move through space at almost the speed of light. About 90 percent of them are protons, with the remainder consisting of electrons and atomic nuclei. In their journey across the galaxy, the electrically charged particles are deflected by magnetic fields. This scrambles their paths and makes it impossible to trace their origins directly.

Through a variety of mechanisms, these speedy particles can lead to the emission of gamma rays, the most powerful form of light and a signal that travels to us directly from its sources.

Since its launch in 2008, Fermi’s Large Area Telescope (LAT) has mapped million- to billion-electron-volt (MeV to GeV) gamma rays from supernova remnants. For comparison, the energy of visible light is between 2 and 3 electron volts.

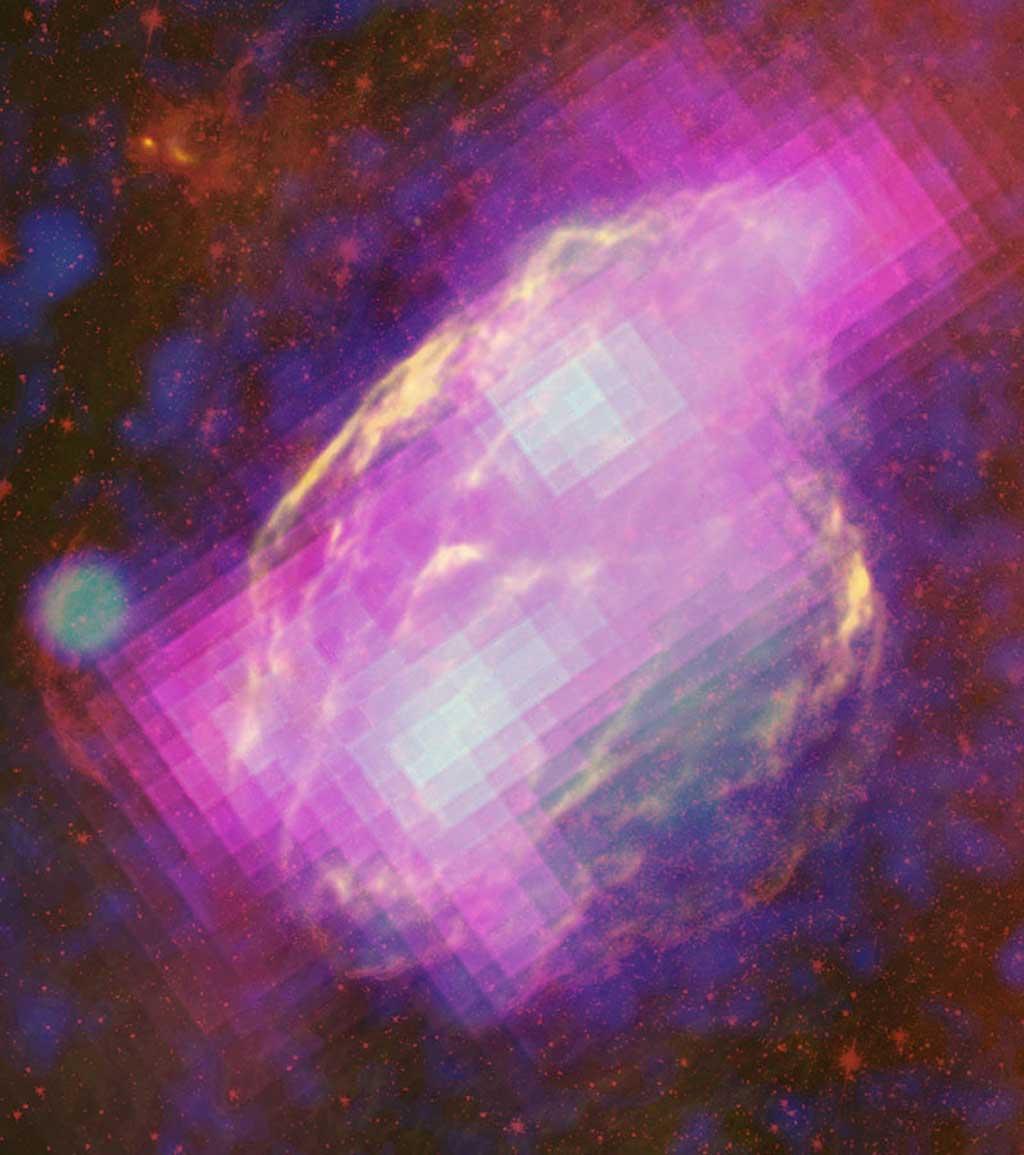

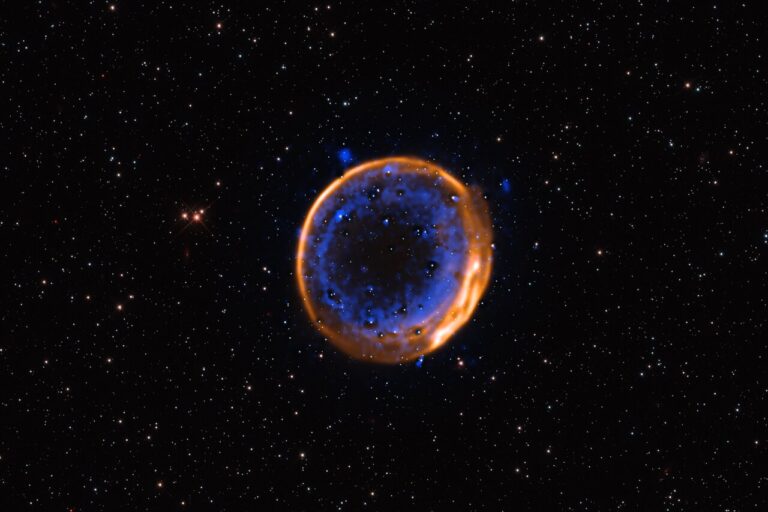

The Fermi results concern two particular supernova remnants, known as IC 443 and W44, which scientists studied to prove supernova remnants produce cosmic rays. IC 443 and W44 are expanding into cold dense clouds of interstellar gas. These clouds emit gamma rays when struck by high-speed particles escaping the remnants.

Related: “The Very Large Telescope probes remains of medieval supernova“

Scientists previously could not determine which atomic particles are responsible for emissions from the interstellar gas clouds because cosmic-ray protons and electrons give rise to gamma rays with similar energies. After analyzing four years of data, Fermi scientists see a distinguishable feature in the gamma-ray emission of both remnants. The feature is caused by a short-lived particle called a neutral pion, which is produced when cosmic-ray protons smash into normal protons. The pion quickly decays into a pair of gamma rays, emission that exhibits a swift and characteristic decline at lower energies. The low-end cutoff acts as a fingerprint, providing clear proof that the culprits in IC 443 and W44 are protons.

“The discovery is the smoking gun that these two supernova remnants are producing accelerated protons,” said Stefan Funk from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford University in California. “Now we can work to better understand how they manage this feat and determine if the process is common to all remnants where we see gamma-ray emission.”

In 1949, the Fermi telescope’s namesake, physicist Enrico Fermi, suggested the highest-energy cosmic rays were accelerated in the magnetic fields of interstellar gas clouds. In the decades that followed, astronomers showed supernova remnants were the galaxy’s best candidate sites for this process.

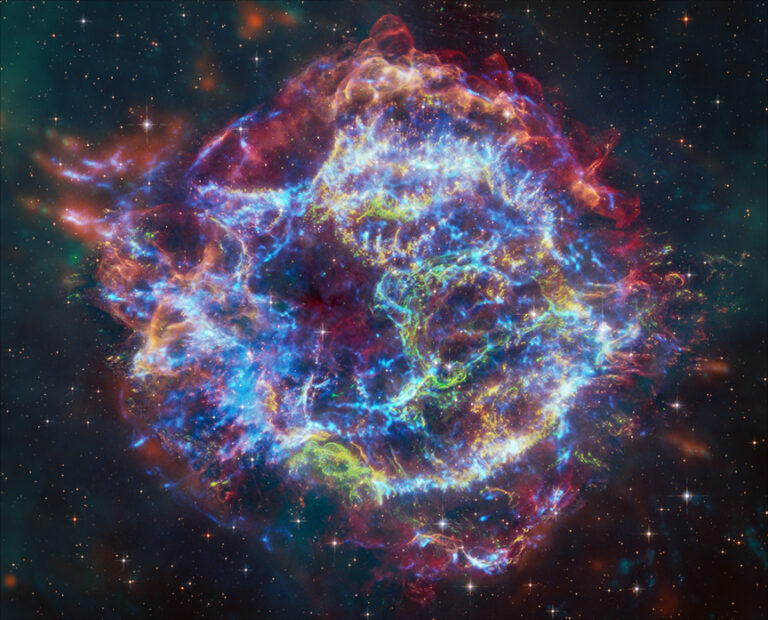

A charged particle trapped in a supernova remnant’s magnetic field moves randomly throughout the field and occasionally crosses through the explosion’s leading shock wave. Each round trip through the shock ramps up the particle’s speed by about 1 percent. After many crossings, the particle obtains enough energy to break free and escape into the galaxy as a newborn cosmic ray.

The supernova remnant IC 443, popularly known as the Jellyfish Nebula, is located 5,000 light-years away toward the constellation Gemini and is thought to be about 10,000 years old. W44 lies about 9,500 light-years away toward the constellation Aquila and is estimated to be 20,000 years old. Each is the expanding shock wave and debris formed when a massive star exploded.