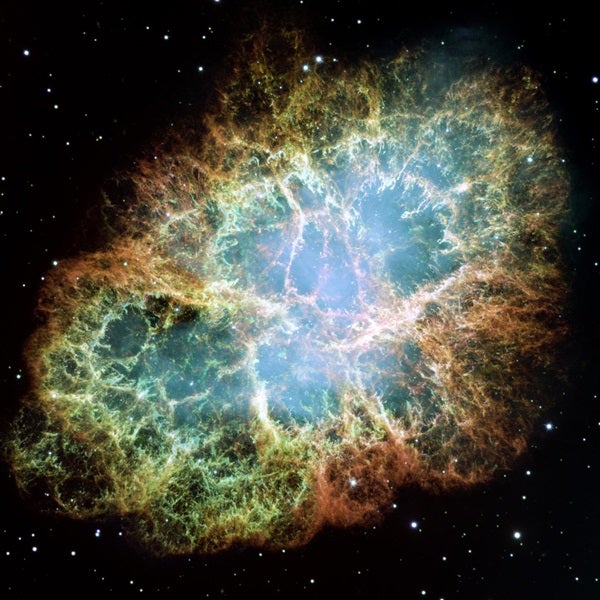

The nebula is the wreckage of an exploded star, which emitted light that reached Earth in 1054. It is located 6,500 light-years away in the constellation Taurus. At the heart of an expanding gas cloud lies what is left of the original star’s core, a super-dense neutron star that spins 30 times per second. With each rotation, the star swings intense beams of radiation toward Earth, creating the pulsed emission characteristic of spinning neutron stars — also known as pulsars.

Apart from these pulses, astrophysicists believed the Crab Nebula was a virtually constant source of high-energy radiation. But in January, scientists associated with several orbiting observatories, including NASA’s Fermi, Swift, and Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer, reported long-term brightness changes at X-ray energies.

“The Crab Nebula hosts high-energy variability that we’re only now fully appreciating,” said Rolf Buehler from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology.

Since 2009, Fermi and the Italian Space Agency’s AGILE satellite have detected several short-lived gamma-ray flares at energies greater than 100 million electron volts (eV) — hundreds of times higher than the nebula’s observed X-ray variations. For comparison, visible light has energies between 2 and 3 eV.

On April 12, Fermi’s LAT, and later AGILE, detected a flare that grew about 30 times more energetic than the nebula’s normal gamma-ray output and about 5 times more powerful than previous outbursts. On April 16, an even brighter flare erupted, but within a couple of days the unusual activity completely faded out.

“These superflares are the most intense outbursts we’ve seen to date, and they are all extremely puzzling events,” said Alice Harding form NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “We think they are caused by sudden rearrangements of the magnetic field not far from the neutron star, but exactly where that’s happening remains a mystery.”

The Crab’s high-energy emissions are thought to be the result of physical processes that tap into the neutron star’s rapid spin. Theorists generally agree the flares must arise within about one-third of a light-year from the neutron star, but efforts to locate them more precisely have proven unsuccessful so far.

Since September 2010, NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory routinely has monitored the nebula in an effort to identify X-ray emission associated with the outbursts. When Fermi scientists alerted astronomers to the onset of a new flare, Martin Weisskopf and Allyn Tennant from NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, triggered a set of pre-planned observations using Chandra.

“Thanks to the Fermi alert, we were fortunate that our planned observations actually occurred when the flares were brightest in gamma rays,” Weisskopf said. “Despite Chandra’s excellent resolution, we detected no obvious changes in the X-ray structures in the nebula and surrounding the pulsar that could be clearly associated with the flare.”

Scientists think the flares occur as the intense magnetic field near the pulsar undergoes sudden restructuring. Such changes can accelerate particles like electrons to velocities near the speed of light. As these high-speed electrons interact with the magnetic field, they emit gamma rays.

To account for the observed emission, scientists say the electrons must have energies 100 times greater than can be achieved in any particle accelerator on Earth. This makes them the highest-energy electrons known to be associated with any galactic source. Based on the rise and fall of gamma rays during the April outbursts, scientists estimate that the size of the emitting region must be comparable in size to the solar system.