When two white dwarfs in a binary star system eventually spiral in toward each other and collide, the result is usually mutually assured destruction: a thermonuclear explosion that consumes both stars and scatters their remains into the cosmos.

But astronomers have found one case where such a collision resulted in fireworks of a different kind.

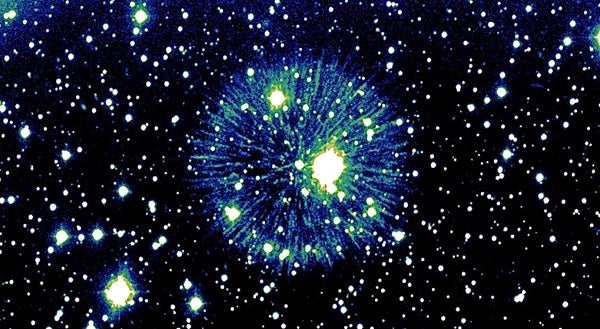

New observations of the faint nebula Pa 30 have revealed that it is surrounded by filaments of glowing sulfur gas, appearing like the trails of sparks blown outward by an exploding fireworks shell. Astronomers think this scene was caused when two white dwarfs collided — and managed to not destroy each other. Instead, they apparently merged and formed a magnetic monster of a star that blows its own material into space, whisking debris from the merger outward to form the sulfuric, streaming contrails.

Researchers say the nebula and its central star comprise a unique object with scarcely any observational precedent. “I’ve worked on supernova remnants for 30 years and I’ve never seen anything like this,” said Robert Fesen, of Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. Fesen was speaking Jan. 12 in Seattle at the winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), where he presented his team’s results at a press conference. “There’s nothing like this in our galaxy.” A draft of their report is available on the arXiv preprint server and has been accepted for publication by The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

It is “a really interesting” object, said Benson Guest, an X-ray astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who wasn’t involved with the study. “These things are very hard to detect because they’re not very bright compared to a normal supernova, so you’re looking for a very faint transient [object].”

The new imagery bolsters the case that Pa 30 is what astronomers call a Type Iax supernova — a type of “failed” supernova that results in a relatively tepid burst of light and leaves behind a surviving star. These have been observed in distant galaxies, but “this would be the first one we’ve ever found” in the Milky Way that we can easily study, said Guest. “Any time you can say that in astronomy, that’s something that’s really cool.”

What’s more, the new observations also pins down the object’s age — and give it a strong case for being the solution to a 900-year-old astronomical mystery.

Overlooked gem

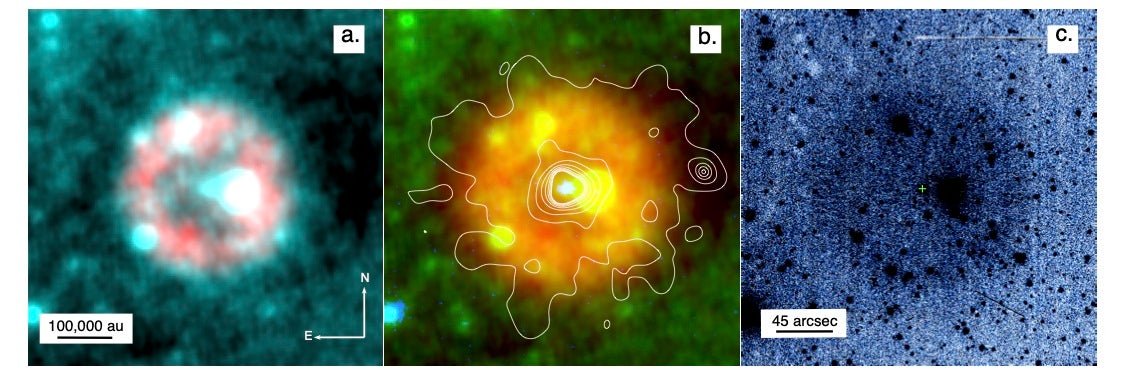

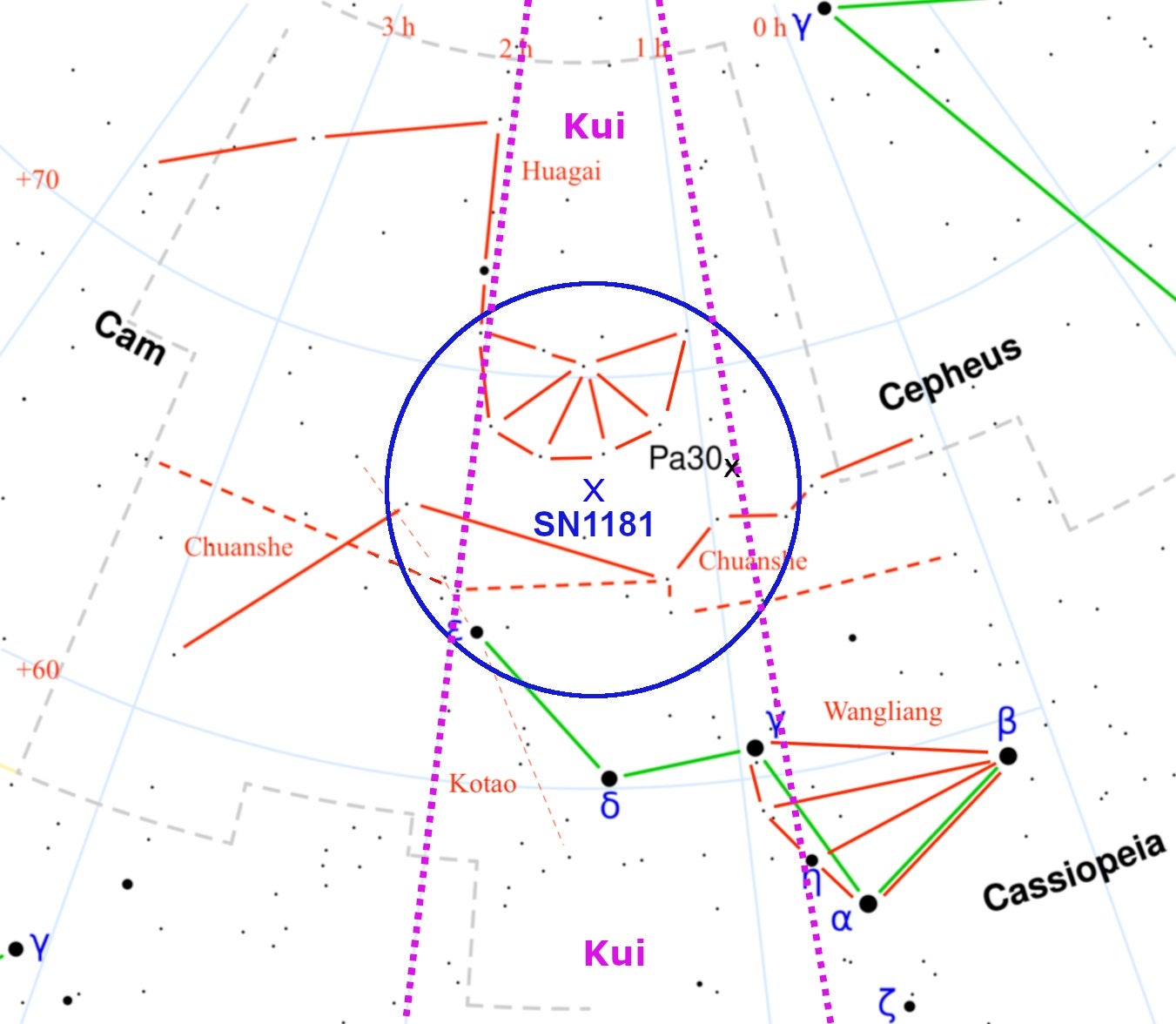

Pa 30 lies just 7,500 light-years away in Cassiopeia and spans roughly 3′ (or about one-tenth the width of the Full Moon). It was discovered by amateur astronomer Dana Patchik in 2013 as he was searching archival data from NASA’s Wide Infrared Survey Satellite (WISE). In that data, the object had a rather conventional circular, doughnut-like appearance, resembling a planetary nebula — an object formed when an aging star sheds its outer layers of gas into space and then irradiates that gas, exciting it and causing it to glow.

Over the next few years, multiple professional observatories conducted follow-up observations, including the 10-meter Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC) on La Palma. But they barely detected any emission from hydrogen, oxygen, or nitrogen gas. With apparently nothing to study, the researchers never fully scrutinized the data.

Interest in the object picked up again in 2018, when some French amateur astronomers using an 8-inch scope found that the nebula was harboring a very blue star at its center. They notified one of the research groups that had observed Pa 30, a team at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), who began reanalyzing their data.

But they were beaten to publication in 2019 by a Russian team that had noted the same thing. Using the Russian 6-meter telescope in the Caucasus Mountains, they obtained a spectrum that revealed this star had some jaw-dropping qualities: It shines with the brightness of 36,000 Suns thanks to a temperature of about 200,000 degrees Celsius (360,000 degrees Fahrenheit) at its surface, from which a wind of material zips into space at 35 million mph (57,000 km/h). Writing in Nature, the Russian team proposed that the star was the remnant of a double-white dwarf Type Iax supernova, spinning rapidly with a magnetic field strong enough to accelerate the winds.

Fresh evidence for a cold case

When the HKU team published their results in 2021 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, they added new insights. First, they found that while the nebula didn’t have much glowing oxygen gas, it did have some sulfur. Their spectra revealed that this sulfur is traveling away from the central star at about 2.5 million mph (4 million km/hr). Assuming this is debris from the Type Iax supernova, and using the WISE image as a reference for how far this gas had traveled, they estimated that the supernova had occurred about 1,000 years ago, plus or minus about 250 years.

This, the HKU team noticed, meant Pa 30 might hold the key to solving a historical supernova mystery. In 1181, Chinese and Japanese astronomers recorded a “guest star” in this region of the sky. It was only about as bright as the brightest star — perhaps magnitude –1, rather modest for a supernova in our galaxy.

Since the 1970s, scientists had thought that the remnant of this event was a nebula called 3C 58 that housed a pulsar, a type of rapidly rotating neutron star leftover from a supernova. But that was called into question by observations in the past few decades that estimated 3C 58 was more like 2,500 years old. 3C 58 was too static in the sky and too cool to be linked to the death of a star as recent as SN 1181. Pa 30’s age, as estimated by the HKU team, was a better fit, though there was still much uncertainty.

Fesen and his colleague Bradley Schaefer of Louisiana State University saw an opportunity to do one better. Most professional observatories — and all of the ones that had so far observed Pa 30 — are only designed to use filters that allow a relatively large range of wavelengths to pass through. This is the same reason that professional astronomers never noticed the enormous oxygen emission feature right next to the Andromeda Galaxy that was recently discovered by a team of amateur astronomers using narrowband filters. (Fesen was also a co-author on that study.)

Fesen, Schaefer, and Patchik were able to use a narrow passband Sulfur-II filter on the 2.4-meter Hiltner telescope at Kitt Peak. It was “low-hanging fruit,” Fesen told Astronomy at the AAS meeting in Seattle. “In fact, it was so low, it was on the ground,” he joked. It is a standard technique and methodology, agrees Guest. “It’s just a nonstandard object.”

The result was stunning: With a filter capable of blocking out much more background noise, what had appeared as a hazy blob was revealed to instead be fine contrails of gas driven outward by the high winds of the central star. “It’s beautifully symmetric,” said Fesen.

The clarity of these features allowed the team to much more precisely determine how far the sulfur gas had traveled from its central star. Combining that measurement with the sulfur-derived velocity of 2.5 million mph (4 million km/hr), they could narrow down PA 30’s age: 844 years, plus or minus 55 years — nearly an exact match to the 842-year age of SN 1181. “Well, that’s ridiculously good … almost too good,” said Fesen. “Finally, we have really nailed down the remains of the star that the Chinese and Japanese saw in early August of 1181 A.D.”

Fesen and his colleagues hope to obtain follow-up observations of the object with the Hubble or James Webb space telescopes, which “should be amazing,” he said. He says the object will lend more insight into the physics of Type Iax supernovae and how exactly a star survives, of which astronomers know little.

“There’s beauty, science, and history in the story,” Fesen said. “We’ve never seen a Iax in our galaxy. So here we have one that’s just a few thousand light years away.”