A narrow belt harboring moonlets as large as football stadiums, probably resulted when a larger moon was shattered by a wayward asteroid or comet eons ago, according to a University of Colorado at Boulder study.

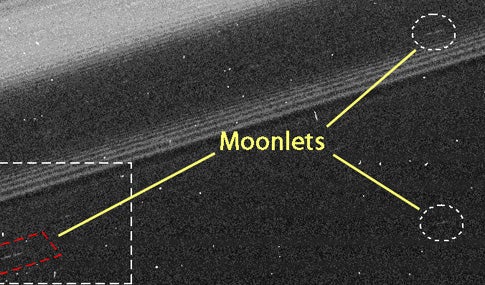

Images taken onboard the NASA Cassini spacecraft revealed a series of eight propeller-shaped “wakes” in a thin belt of Saturn’s outermost “A” ring, indicating the presence of corresponding moonlets, said Miodrag Sremcevic, research associate for CU-Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics and lead author of the study published in the Oct. 25 issue of Nature. The propeller wakes highlight tiny areas of the belt where ring material has been perturbed by the gravitational forces caused by individual moonlets, Sremcevic said.

“This is the first evidence of a moonlet belt in any of Saturn’s rings,” said Sremcevic. “We have firmly established these moonlets exist in a relatively narrow region of the “A” ring, and the evidence indicates they are remnants of a larger moon that was shattered by a meteoroid or comet.”

Co-authors of the Nature study include Juergen Schmidt, Martin Seiss and Frank Spahn of the University of Potsdam in Germany, Heikko Salo of the University of Oulu in Finland, and Nicole Albers of CU-Boulder’s LASP.

The images were taken by the Narrow Angle Camera onboard the NASA Cassini spacecraft, which was launched in 1997 and has been orbiting the Saturn system since July 2004.

Each propeller feature is about 10 miles long, said Sremcevic, who with Spahn, first predicted the existence of such propellers in Saturn’s rings as an undergraduate at the University of Belgrade in 2000. While four propellers were discovered in the “A” ring in 2006 by a team led by Cornell University, Sremcevic and his colleagues looked at a much larger image sequence, allowing them to extrapolate statistically and confirm the presence of thousands of small objects in the “A” ring’s moonlet belt.

The moonlets may be the result of the break-up of a ring-moon similar to Pan — Saturn’s innermost 20-mile diameter moon — that was smashed by a comet or meteor, the team concluded. The team calculated the mass of the unseen moonlets in the belt, greater than 50 feet in diameter, to arrive at the estimated size of the moon involved in the collision creating the belt.

The finding supports the theory that Saturn’s rings initially were created in a “collision cascade” of ring debris begun by a catastrophic break-up of an even larger moon in the Saturn system. CU-Boulder planetary scientists Larry Esposito and Joshua Colwell first proposed this idea in 1987. The moonlets in the newly discovered belt may have formed after Saturn’s rings already were in place, which planetary scientists speculate could have been hundreds of millions or even billions of years ago.

“It seems unlikely that moonlets are remainders of a single catastrophic event that created the whole ring system, because in this case a uniform distribution would emerge,” the researchers wrote in Nature. “Instead, the moonlet belt is compatible with a more recent body orbiting in the A ring.”

Esposito, who was not involved in the study, said the propellers “show a striking demonstration of the lingering effects of the gravity from these small, embedded moonlets.” Esposito is the chief scientist on the NASA Cassini mission’s $12.5 million Ultra-Violet Imaging Spectrograph, designed and built at LASP.

Sremcevic said the discovery of the moonlet belt is another piece in the puzzle regarding the formation and evolution of Saturn’s rings. “We believe future studies of ring evolution will need to incorporate the findings and implications from this study.”