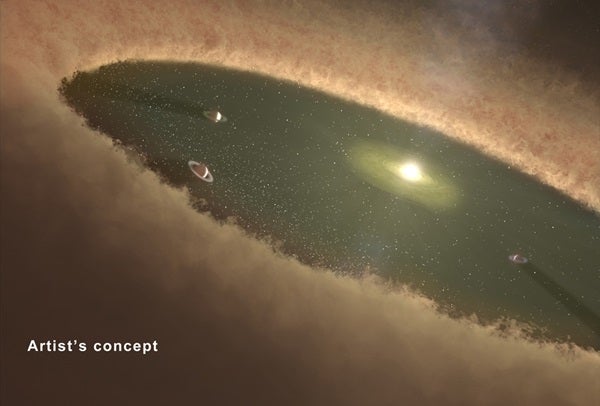

The dusty star system, called HD 95086, is located 295 light-years from Earth in the constellation Carina. It is thought to include two belts of dust, which lie within the newfound outer dust halo. One of these belts is warm and closer to its star, as is the case with our solar system’s asteroid belt, while the second belt is cooler and farther out, similar to our own Kuiper belt of icy comets.

“By looking at other star systems like these, we can piece together how our own solar system came to be,” said Kate Su, an associate astronomer at the University of Arizona, Tucson.

Within our solar system, the planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune are sandwiched between the two dust belts. Scientists think something similar is happening in the star system HD 95086, only on larger scales. One planet, about five times the mass of Jupiter, is already known to sit right inside HD 95086’s cooler belt. Other massive planets may be lurking between the two dust belts, waiting to be discovered.

Studies like this from Spitzer and Herschel point the way for ground-based telescopes to snap pictures of such planets in hiding, a technique referred to as direct imaging. The one planet known to exist in HD 95086 was, in fact, discovered and imaged using this technique in 2013. The images aren’t sharp because the planets are so faint and far away, but they reveal new information about the global architecture of a planetary system.

“By knowing where the debris is, plus the properties of the known planet in the system, we can get an idea of what other kinds of planets can be there,” said Sarah Morrison from the University of Arizona. She ran computer models to constrain the possibilities of how many planets are likely to inhabit the system. “We know that we should be looking for multiple planets instead of a single giant planet.”

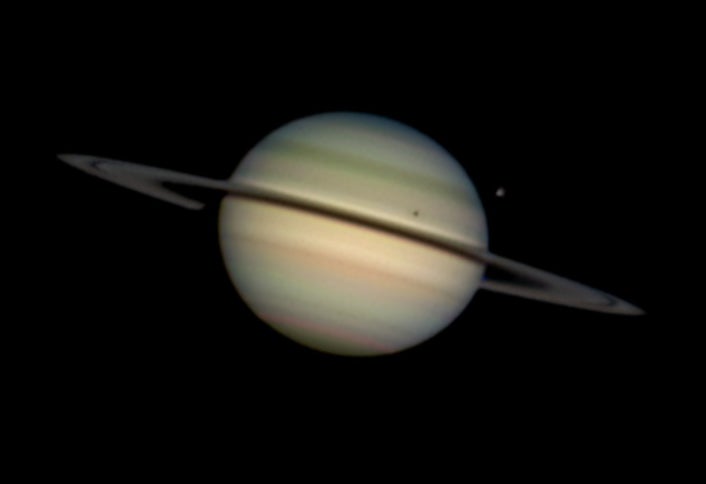

To learn what HD 95086 looks like, the astronomers turned to a similar star system called HR 8799. It too has an inner and outer belt of debris surrounded by a large halo of fine dust, and four known planets between the belts — among the first exoplanets, or planets beyond our solar system, to be directly imaged.

Comparing data from the two star systems hints that HD95086, like its cousin HR 8799, is a possible home to multiple planets that have yet to be seen. Ground-based telescopes might be able to take pictures of the family of planets.

Both HD 95086 and HR 8799 are much younger and dustier than our solar system. When planetary systems are young and still forming, collisions between growing planetary bodies, asteroids, and comets kick up dust. Some of the dust coagulates into planets, some winds up in the belts, and the rest is either blown out into a halo, or funneled onto the star.

Herschel and Spitzer are ideally suited to study the dust structures in these systems, which glow at the infrared wavelengths the telescopes detect.