New findings challenge a theory that a meteor explosion or impact thousands of years ago caused catastrophic fires over much of North America and Europe, and it triggered an abrupt global cooling period called the Younger Dryas. Whereas proponents of the theory have offered “carbonaceous spherules” and nanodiamonds, both of which they claimed were formed by intense heat as evidence of the impact, a new study concludes that those supposed clues are nothing more than fossilized balls of fungus, charcoal, and fecal pellets. Moreover, these naturally occurring organic materials, some of which had likely been subjected to normal cycles of wildfires, date from a period thousands of years both before and after the time that the Younger Dryas period began, further suggesting that there was no sudden impact event.

“People get very excited about the idea of a major impact causing a catastrophic fire and the abrupt climate change in that period, but there just isn’t the evidence to support it,” said Andrew C. Scott of the Department of Earth Sciences at Royal Holloway, University of London.

The Younger Dryas impact event theory holds that a large meteor struck Earth or exploded in the atmosphere about 12,900 years ago, causing a vast fire over most of North America, which contributed to extinctions of most of the large animals on the continent and triggered a thousand-year-long cold period. While there is previous evidence for the abrupt onset of a cooling period at that time, other researchers have theorized that the climatic change resulted from increased freshwater in the ocean, changes in ocean and atmospheric circulation patterns, or other causes unrelated to impacts.

The impact-theory proponents point to a charred layer of sediment filled with organic material that they say is unique to that period as evidence of such an event. These researchers describe carbon spheres, carbon cylinders, and charcoal pieces that they conclude are melted and charred organic matter created in the intense heat of a widespread fire.

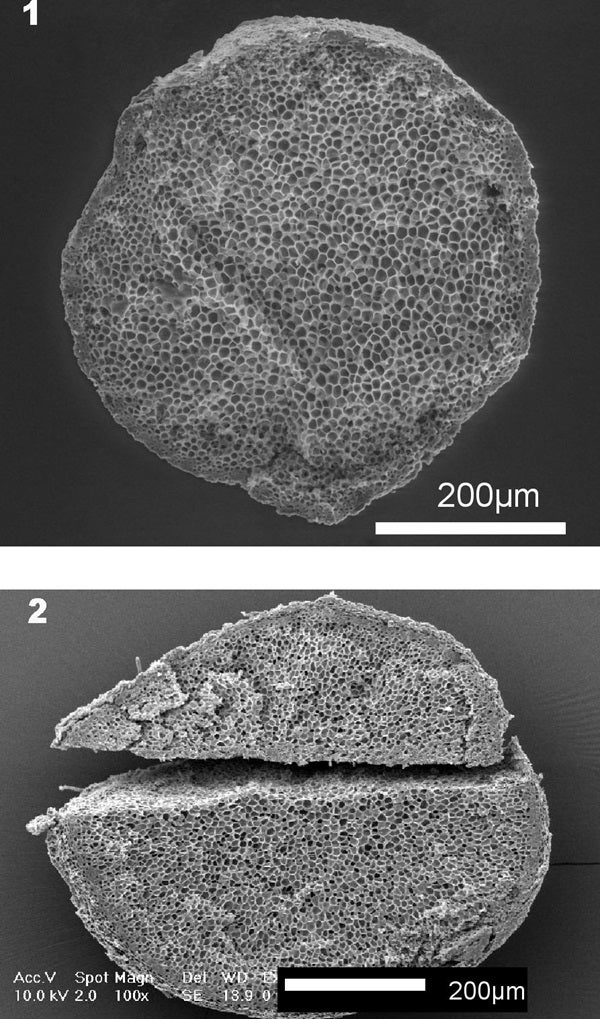

Scott and his fellow researchers analyzed sediment samples to determine the origins of the carbonaceous particles. After comparing the fossil particles with modern fungal ones exposed to low to moderate heat (less than 932°Fahrenheit [500° Celsius]), Scott’s group concludes that the particles are actually

balls of fungal material and other ordinary organic particles, such as fecal pellets from insects, plant or fungal galls, and wood, some of which may have been exposed to regularly occurring low-intensity wildfires.

The researchers used microscopic analysis of particles from the Pleistocene-Holocene sediments collected from the California Channel Islands and compared them with modern soil samples that had been subjected to wildfires as well as balls of stringy fungal material, called sclerotia, some of which were also subjected to a range of temperatures in a laboratory. Many soil and plant fungi produce sclerotia — tough balls of cells that are usually 0.02 inch to 0.08 inch (0.5 millimeter to 2 millimeters) in size — as a way to survive periods of harsh conditions. Their shape can vary from spherical to elongated, and their internal structures, which can take on a spongy or honeycomb pattern, matches the descriptions given by Dryas-impact event proponents.

Further, the group studied the amount of light reflected by the fossil spherules and wood charcoal from the sediment layers that included the Dryas period. The researchers used the reflectance of the organic material to determine the amount of heat to which it had been subjected. They found that the fossilized matter was unlikely to have been exposed to temperatures above 842° Fahrenheit (450° Celsius). Radiocarbon dating also showed that the particles taken from several layers ranged in age from 16,821 to 11,467 years ago. Proponents of the impact theory had reported that the spherules they found in the Younger Dryas sediment layer dated to a very narrow time period of 12,900 to 13,000 years ago.

“There is a long history of fire in the fossil record, and these fungal samples are common everywhere from ancient times to the present,” Scott said. “These data support our conclusion that there wasn’t one single intense fire that triggered the onset of the cold period.”