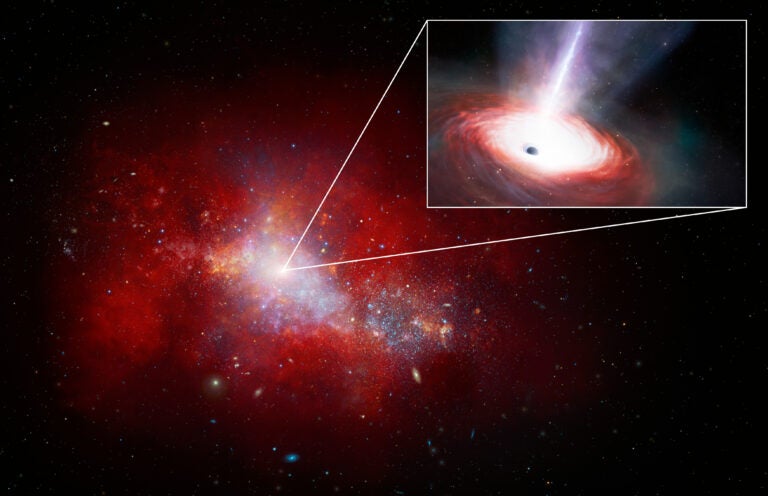

The candidate black hole duo, called PG 1302-102, was first identified earlier this year using ground-based telescopes. The black holes are the tightest orbiting pair detected so far, with a separation not much bigger than the diameter of our solar system. They are expected to collide and merge in less than a million years, triggering a titanic blast with the power of 100 million supernovae.

Researchers are studying this pair to better understand how galaxies and the monstrous black holes at their cores merge — a common occurrence in the early universe. But as common as these events were, they are hard to spot and confirm.

PG 1302-102 is one of only a handful of good binary black hole candidates. It was discovered and reported earlier this year by researchers at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena after they scrutinized an unusual light signal coming from the center of a galaxy. The researchers, who used telescopes in the Catalina Real-Time Transient Survey, demonstrated that the varying signal is likely generated by the motion of two black holes that swing around each other every five years. While the black holes themselves don’t give off light, the material surrounding them does.

In the new study, researchers found more evidence to support and confirm the close-knit dance of these black holes. Using ultraviolet data from GALEX and Hubble, they were able to track the system’s changing light patterns over the past 20 years.

“We were lucky to have GALEX data to look through,” said David Schiminovich of Columbia University in New York. “We went back into the GALEX archives and found that the object just happened to have been observed six times.”

Hubble, which sees ultraviolet light in addition to visible and other wavelengths of light, had likewise observed the object in the past.

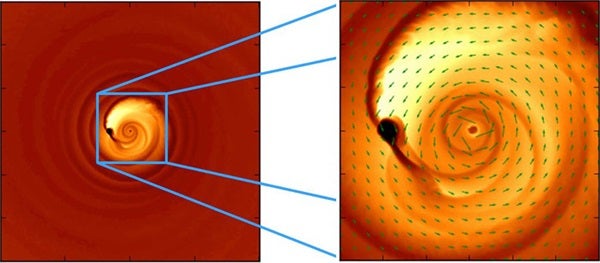

The ultraviolet light was important to test a prediction of how the black holes generate a cyclical light pattern. The idea is that one of the black holes in the pair is giving off more light — it is gobbling up more matter than the other one, and this process heats up matter that emits energetic light. As this black hole orbits around its partner every five years, its light changes and appears to brighten as it heads toward us.

“It’s as if a 60-watt light bulb suddenly appears to be 100 watts,” said Daniel D’Orazio from Columbia University. “As the black hole light speeds away from us, it appears as a dimmer 20-watt bulb.”

What’s causing the changes in light? One set of changes has to do with the “blueshifting” effect in which light is squeezed to shorter wavelengths as it travels toward us in the same way that a police car’s siren squeals at higher frequencies as it heads toward you. Another reason has to do with the enormous speed of the black hole.

The brighter black hole is, in fact, traveling at nearly 7 percent the speed of light — in other words, really fast. Though it takes the black hole five years to orbit its companion, it is traveling vast distances. It would be as if a black hole lapped our entire solar system from the outer fringes, where the Oort Cloud of comets lies, in just five years. At speeds as high as this, which are known as relativistic, the light becomes boosted and brighter.

D’Orazio and colleagues modeled this effect based on a previous Caltech paper and predicted how it should look in ultraviolet light. They determined that if the periodic brightening and dimming previously seen in the visible light is indeed due to the relativistic boosting effect, then the same periodic behavior should be present in ultraviolet wavelengths, but amplified 2.5 times. Sure enough, the ultraviolet light from GALEX and Hubble matched their predictions.

“We are strengthening our ideas of what’s going on in this system and starting to understand it better,” said Zoltán Haiman from Columbia University.

The results also will help researchers understand how to find even closer-knit merging black holes in the future, what some consider the holy grail of physics and the search for gravitational waves. In the final moments before the ultimate union of two black holes, when they are tightly spinning around each other like ice skaters in a “death spiral,” they are predicted to send out ripples in space and time. These so-called gravitational waves, whose existence follows from Albert Einstein’s gravity theory published 100 years ago, hold clues about the fabric of our universe.

The findings are also a doorway to understanding other merging black holes across the universe, a widespread population that is only now beginning to yield its secrets.