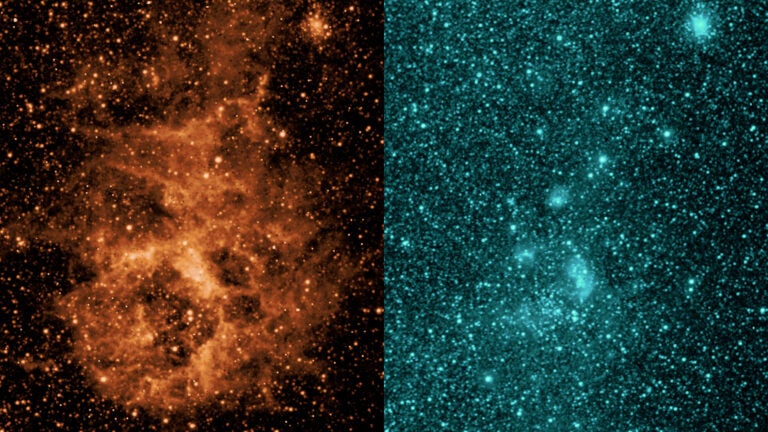

Scientists at Durham’s Institute for Computational Cosmology and their collaborators at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, in Germany, and Groningen University, in Holland, ran huge computer simulations to re-create the beginnings of our galaxy.

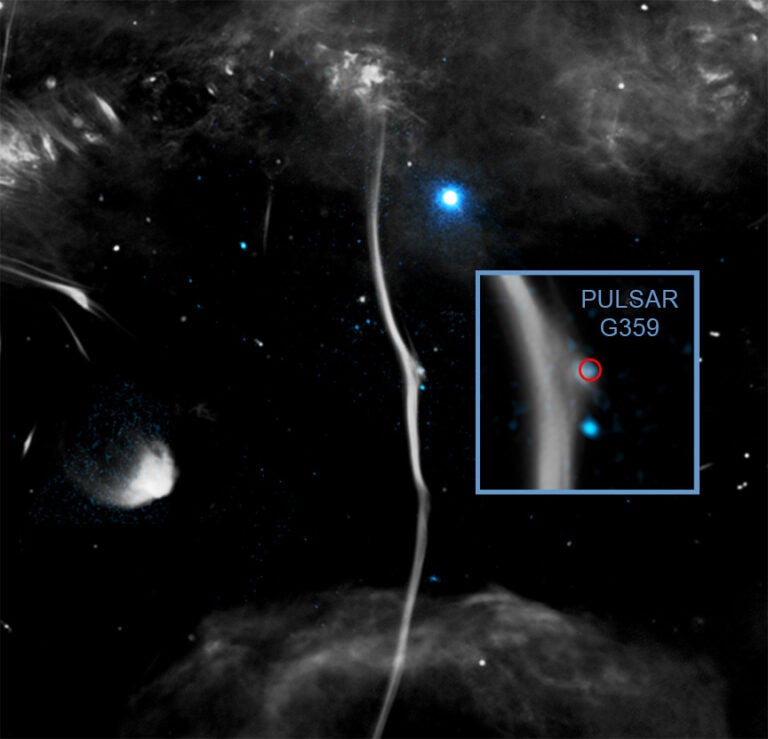

The simulations revealed that the ancient stars, found in a stellar halo of debris surrounding the Milky Way, had been ripped from smaller galaxies by the gravitational forces generated by colliding galaxies.

Cosmologists predict that the early universe was full of small galaxies that led short and violent lives. These galaxies collided with each other, leaving behind debris that eventually settled into more familiar looking galaxies like the Milky Way.

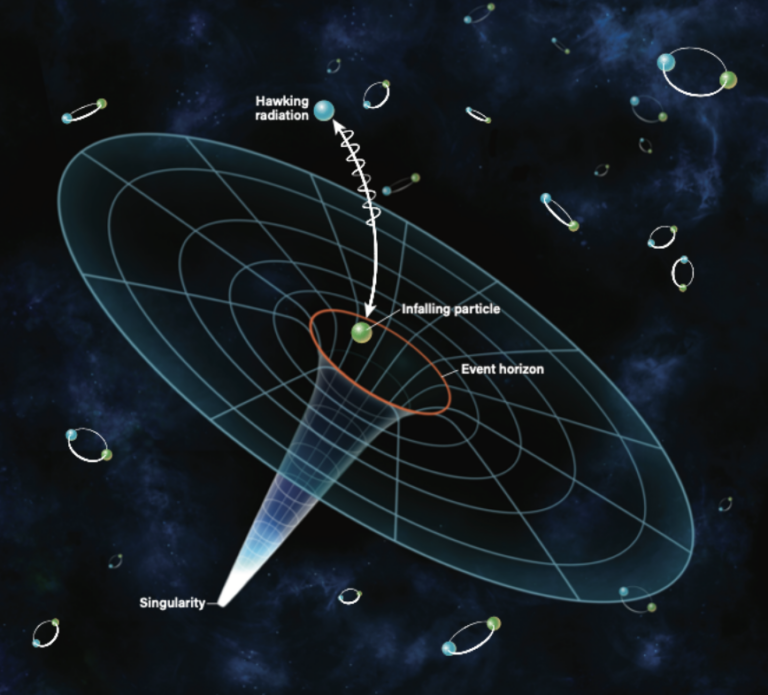

The researchers said their finding supports the theory that many of the Milky Way’s ancient stars had once belonged to other galaxies instead of being the earliest stars born inside the galaxy when it began to form about 10 billion years ago.

Lead author Andrew Cooper, from Durham University’s Institute for Computational Cosmology, said: “Effectively, we became galactic archaeologists, hunting out the likely sites where ancient stars could be scattered around the galaxy.”

“Our simulations show how different relics in the galaxy today, like these ancient stars, are related to events in the distant past,” Cooper added. “Like ancient rock strata that reveal the history of Earth, the stellar halo preserves a record of a dramatic primeval period in the life of the Milky Way which ended long before the Sun was born.”

The computer simulations started from shortly after the Big Bang, around 13 billion years ago, and used the universal laws of physics to simulate the evolution of dark matter and the stars.

These simulations are the most realistic to date, capable of zooming into the very fine detail of the stellar halo structure, including star “streams” — which are stars being pulled from the smaller galaxies by the gravity of the dark matter.

One in 100 stars in the Milky Way belongs to the stellar halo, which is much larger than the galaxy’s familiar spiral disk. These stars are almost as old as the universe.

Professor Carlos Frenk, director of Durham University’s Institute for Computational Cosmology, said: “The simulations are a blueprint for galaxy formation. They show that vital clues to the early, violent history of the Milky Way lie on our galactic doorstep.”

“Our data will help observers decode the trials and tribulations of our galaxy in a similar way to how archaeologists work out how ancient Romans lived from the artifacts they left behind,” Frenk added.