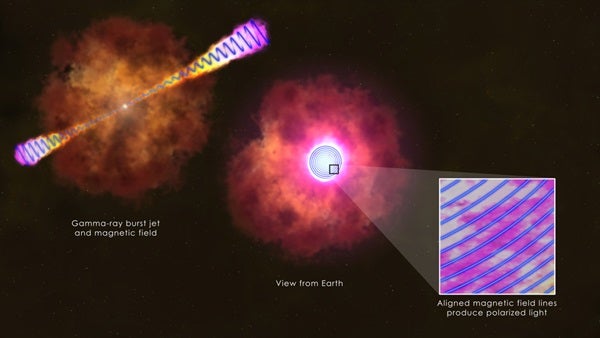

Gamma-ray bursts are the most luminous explosions in the cosmos. Most are thought to be triggered when the core of a massive star runs out of nuclear fuel, collapses under its own weight, and forms a black hole. The black hole then drives jets of particles that drill all the way through the collapsing star and erupt into space at nearly the speed of light.

On March 8, 2012, NASA’s Swift satellite detected a 100-second pulse of gamma rays from a source in the constellation Ursa Minor. The spacecraft immediately forwarded the location of the gamma-ray burst, dubbed GRB 120308A, to observatories around the globe.

The world’s largest fully autonomous robotic optical telescope, the 2-meter Liverpool Telescope located at Roque de los Muchachos Observatory on La Palma in the Canary Islands, automatically responded to Swift’s notification.

“Just four minutes after it received Swift’s trigger, the telescope found the burst’s visible afterglow and began making thousands of measurements,” said Carole Mundell from the Astrophysics Research Institute at Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom.

The telescope was fitted with an instrument named RINGO2, which Mundell’s team designed to detect any preferred direction, called polarization, in the vibration of light waves from burst afterglows.

Mundell’s team built RINGO2 in order to probe the magnetic fields long postulated to drive and focus the jets of gamma-ray bursts. The shoe-box-sized instrument pairs a spinning polarizing filter with a super-fast camera.

Energy across the spectrum, from radio waves to gamma rays, is emitted when a jet slams into its surroundings and begins to decelerate. This results in the formation of an outward-moving shock wave. At the same time, a reverse shock wave drives back into the jet debris, also producing bright emission.

“One way to picture these different shocks is by imagining a traffic jam,” Mundell said. “Cars approaching the jam abruptly slow down, which is similar to what happens in the forward shock. Cars behind them slow in turn, resulting in a wave of brake lights that moves backward along the highway, much like the reverse shock.”

Theoretical models of gamma-ray bursts predict that light from the reverse shock should show strong and stable polarized emissions if the jet possesses a structured magnetic field originating from the environment around the newly-formed black hole, thought to be the “central engine” driving the burst.

Previous observations of optical afterglows detected polarizations of about 10 percent, but they provided no information about how this value changed with time. As a result, they could not be used to test competing jet models.

The Liverpool Telescope’s rapid targeting enabled the team to catch the explosion just four minutes after the initial outburst. Over the following 10 minutes, RINGO2 collected 5,600 photographs of the burst afterglow while the properties of the magnetic field were still encoded in its captured light.

The observations show that the initial afterglow light was polarized by 28 percent, the highest value ever recorded for a burst, and slowly declined to 16 percent while the angle of the polarized light remained the same. This supports the presence of a large-scale organized magnetic field linked to the black hole, rather than a tangled magnetic field produced by instabilities within the jet itself.

“This is a remarkable discovery that could not have occurred without the lickety-split response times of the Swift satellite and the Liverpool Telescope,” said Neil Gehrels from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.