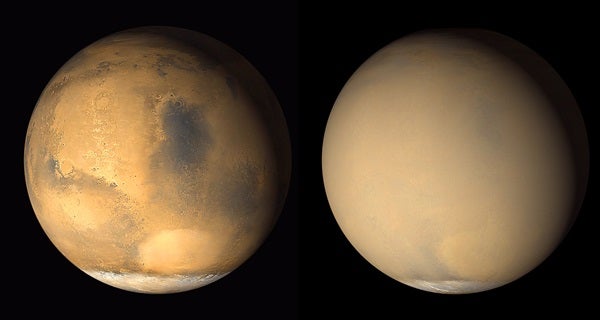

The prospect of a colossal dust storm taking over our planetary neighbor in 2018 has some researchers excited. Mars hasn’t had a global dust storm since 2007, and while scientists were able to observe the event in the past, the current instruments in orbit around the Red Planet would allow us to study a storm of this magnitude in never-before-seen detail.

Observing a global storm with more advanced technology could corroborate the findings of a study published in Nature Astronomy January 22, which used data collected by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) during the 2007 event to link storm activity with hydrogen gas leaking from Mars’ atmosphere — the process that ultimately transformed Mars from a wetter, possibly lusher planet into the arid place it is today.

Using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and the European Space Agency’s Mars Express orbiter, “we found there’s an increase in water vapor in the middle atmosphere [which spans from about 30 to 60 miles (50 to 100 kilometers) above the planet] in connection with dust storms,” said lead author of the study, Nicholas Heavens of Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia, in a press release. “Water vapor is carried up with the same air mass rising with the dust.”

However, these correlations were made during years with mild dust storm activity and the connection was quite subtle. In 2014, NASA’s MAVEN mission was sent to Mars to further study the phenomenon, and the data it sent back, coupled with observations from MRO, differed from what researchers had predicted.

It was previously believed that hydrogen was leaking from Mars’ atmosphere at a relatively constant rate, with fluctuations being caused by changes in the flow of charged particles from the Sun’s solar winds. However, data from MRO’s Mars Climate Sounder, which is capable of directly identifying ice and dust particles and indirectly identifying concentrations of water vapor, contradicted this theory. It found that the 2007 global dust storm caused more than a hundred-fold increase in middle atmosphere water vapor, while regional dust storms also caused subtle increases in water vapor in the middle atmosphere, leading to more hydrogen gas escaping.

Obtaining data to support this newfound link could be within close reach, as researchers anticipate the next dust storm season to begin in summer 2018 and continue into early 2019. While many are anxiously awaiting the storm, others are busy taking precautionary measures to protect existing and upcoming missions. In the case of a global storm, researchers would have to prepare for decreased energy on Opportunity (a solar-powered rover), lower visibility on all rover and orbiter cameras, and potential adjustments to Mars InSight’s descent, a mission scheduled to land on Mars in November 2018.

While the majority of regional dust storms die out, those in 1977, 1982, 1994, 2001 and 2007 all expanded into global storms. With storm season right around the corner, researchers, whether they’re dreading the event or actively looking forward to it, should be prepared to add 2018 to the list.