Small changes in the positions of nearly 130,000 stars tracked over a 7-year period reveal that globular clusters do, in fact, take part in mass segregation. Mass segregation is the process of heavier stars slowing and sinking to the cluster’s core while lighter stars pick up speed and move toward the cluster’s edge.

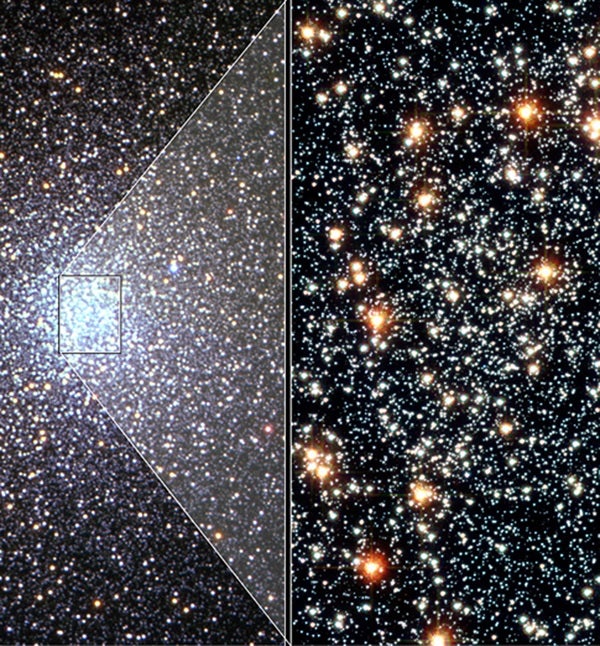

Using the Hubble Space Telescope’s (HST) Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 and the Advanced Camera for Surveys, astronomer Georges Meylan (École Polytechnique Federale de Laussane) led researchers in taking 10 sets of multiple images of the center of globular cluster 47 Tucanae (47 Tuc). HST accomplished in 7 years what might have taken ground-based telescopes nearly a century because of poorer observing conditions. Earth’s atmosphere tends to blur individual stars in images from the ground. Images from the orbiting Hubble are precise enough to show the annual movements of stars in the globular cluster accurate to one ten-millionth of a degree.

Globular clusters are massive, spherical systems containing roughly 10,000 to 1 million stars in a diameter of up to roughly 20 light years. Their densities makes them prone to stellar encounters, which makes the theory of mass segregation plausible. However, the density of these areas also makes identifying individual stars nearly impossible – until we had HST’s precision.

Besides their findings on mass segregation, astronomers also found the possible presence of a black hole. “If there is a black hole, it is not more massive than 1,000 to 1,500 solar- masses, but we cannot reject that there may be a black hole [in 47 Tucanae],” said Meylan.

These findings are useful in estimating star ages, which, in turn, allows scientists a more complete view of the history of star formation.

The results were published in the September Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.