A proposed massive hydrogen-fuel production project in Chile has astronomers galvanized in concern and opposition. One astronomer calls the possible Chilean facility a “nightmare” for the Paranal Observatory’s dark skies.

One study has found that Paranal, located in Chile’s Atacama Desert, has the darkest skies of any major astronomical research site. That would change if the plant, called INNA, is built.

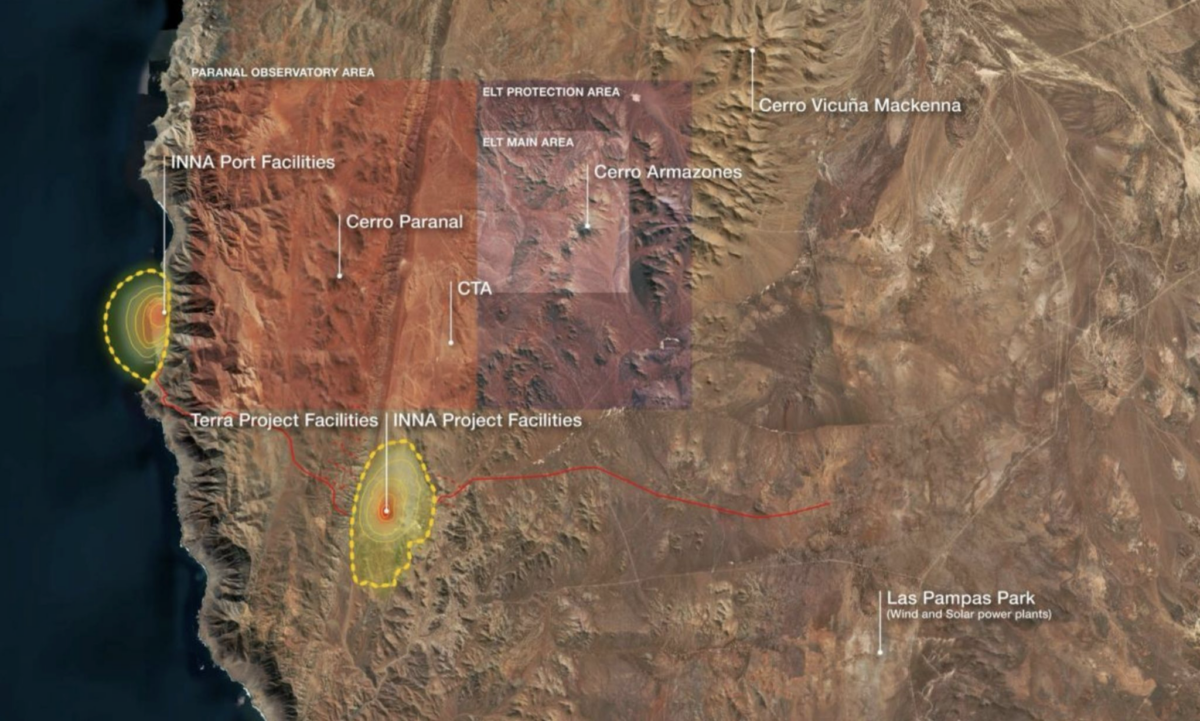

The European Southern Observatory (ESO), which operates Paranal’s astronomical instruments, released news of the hydrogen-plant proposal recently. The project — spearheaded by AES Andes, part of a multinational energy company — would cover some 3,000 hectares, or more than 11 square miles (28.5 square kilometers). It would only be between 3 to 7 miles (5 to 11 km) from the Paranal telescopes and close to Cerro Armazones, where the ESO is already building the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), to be the world’s largest optical instrument. Paranal’s Very Large Telescope (VLT) and interferometer (VLTI) themselves have been active for more than 25 years.

The proposed project is a “green hydrogen” facility that would produce hydrogen using renewable energy. The hydrogen can be used for fuel, fertilizer, and other needs. AES’s website claims it is “a critical fuel of the future to reach net-zero as hydrogen demand, adoption of clean technologies and economic opportunity continue to increase.” Construction, if approved, would begin in two years, last for five, with the facility seeing a four-decade operational life.

The issue of location

No one Astronomy spoke to disputes the need for different energy sources in a world facing increasing climate change. Rather, it’s the location and scale the AES proposal that is so concerning.

The location of the facility will be “if not the worst, one of the most menacing industrial projects to the astronomical activity in Chile,” says Gaspar Galaz, a professor at the Instituto de Astrofísica, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. “The project … is like a story taken from a nightmare of an astronomer. “

The fuel production facilities, roads, lights, a desalination plant, and port on the coast would also affect the planned Cherenkov Telescope Array (CTA), Galaz adds. This array aims to be the first Southern Hemisphere instrument to spot ultra-energetic astrophysical phenomena. “In addition, the CTA will detect blue light,” he says, “one of the most affected wavelengths by light pollution and by dust.”

Indeed, the ESO press release emphasized that “dust emissions during construction, increased atmospheric turbulence [from wind turbines], and especially light pollution will irreparably impact the capabilities for astronomical observation, which have thus far attracted multi-billion-Euro investments by the governments of the ESO Member States.”

An unnecessary choice

ESO Director General Xavier Barcons tells Astronomy that “Chile should not have to make a choice between hosting the most powerful astronomical observatories and developing a green hydrogen production plant. Both are declared strategic priorities by the country and are fully compatible. The only and obvious solution is that the … project moves no less than 50 kilometers [31 miles] away from the Paranal Observatory.”

The project would make research of faint fuzzies difficult, perhaps impossible. Even with instrumentation upgrades and advanced technology, adds Barcons, “sky brightness may be actually a stronger limiting factor.”

According to Chilean officials, the project is under government review and public comments — including from ESO and the scientific community — will be considered. The review must also take into account federal light-pollution regulations.

But Chilean-born Bernardita Ried Guachalla, a physics doctoral student at Stanford, believes the light-pollution law is not strong enough. “The current regulations regulate the emissions of each project or light source and establishes a 1 percent of light pollution limit, without taking into account the cumulative effect of multiple projects,” she says. As well, the rules “establish a value of 10 percent as an acceptable limit for artificial light pollution. This value would make the Paranal Observatory and its telescopes … practically useless.”

While Galaz says that “the most shocking aspect here is that the Chilean authorities have kept an incredible silence regarding this issue,” ESO has been trying to work with AES and the government.

“The Chilean government has set up an inter-ministerial table looking at the challenge and trying to find a solution,” explains Barcons. He notes, however, that AES has been less than cooperative. After ESO gave the company information about the hydrogen plant’s effects and the need to relocate it, AES went ahead and “submitted the project placed next to the Paranal territory, therefore ignoring our request.”

AES tells Astronomy the project’s location in “one of the renewable energy development hubs … aligns with Chile’s National Green Hydrogen Strategy and incorporates the highest standards in lighting in its design.” AES claims that “both the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at Cerro Paranal and the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) at Cerro Armazones are outside the significant impact area calculated for the project. The observatories are 19.6 km and 29 km [12.2 miles and 18 miles] away from INNA, respectively,” which the company says complies with government rules.

AES also says “calculations confirm that the maximum increase over the natural sky brightness is only 0.27 percent at Cerro Paranal and 0.09 percent at Cerro Armazones, both well below the permitted limit, ensuring the protection of these astronomical areas.”

Ried Guachalla questions the distances invoked in this statement; Galaz says “the distance they point out to the VLT … is wrong.” He also says that if AES’s light-pollution claims are correct, “ESO would not have started officially a complaint … nor the astronomical community in Chile would have started to defend anything.”

Related: The fight against light pollution

Astronomy in Chile

The controversy highlights Chile’s unique role in modern astronomy.

Cosmologist and University of Arizona professor Chris Impey puts it this way: “Astronomy is a matter to great pride to Chileans. It has brought prestige, billions of dollars of investment, and thousands of jobs to the country. So protecting it would seem to be a priority for the government.”

Daniela González, the executive director of the Fundación Cielos de Chile, a dark-sky protection organization, agrees: “Chile currently has more than 40 percent of the world’s astronomical observing capacity, and with the development of the new generation of large telescopes being built in the country, this percentage will increase to almost 70 percent. From this perspective, not only is the quality of the dark skies of northern Chile at stake, but it is also a global issue, where the Chilean State must respond to the international scientific community.” She too wants the project moved.

“Chile has a tremendous potential for the generation of renewable energies,” she adds, noting that “there are other sites equally suitable to develop the project.” As well, she believes proponents of the project are overselling its economic benefits. “These companies promise significant amounts of investment and jobs, but in practice they never reach the promised figures.”

Ried Guachalla is helping to spread the word about the AES threat to Paranal. She says she didn’t take the project’s consequences as seriously as she might have early on, but now proclaims: “My commitment is with the sky. Everyone should be as concerned as me.” Still, she urges astronomers using facilities in Chile — especially those coming from abroad — to do more public outreach and engagement in order to better understand the country, to raise scientific literacy and to gain allies.

Currently both AES and ESO have lawyers representing their respective causes, according to Ried Guachalla.

Barcons remains emphatic, saying that “the ELT is the largest optical telescope ever conceived and is being built to scrutinize the deepest and most challenging edges of the universe. It is not a coincidence that the ELT is being erected in the darkest place in the world. We cannot and we should not allow this unparalleled knowledge … to be put out of reach … by degrading the sky at the observing site.”

Related: Sharing the skies above Chile