The cameras aboard the Voyager spacecraft provide an image scale such that a single picture element, or pixel, spans about 2″ on the sky. Image-processing software could improve this resolution by a factor of 4, so, in principal, the Voyager cameras could measure a change in the position of a star as small as 0.5″.

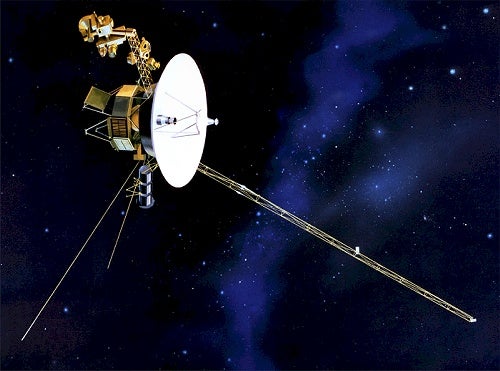

A couple of decades ago, the Voyagers could’ve provided astronomers with a baseline of 30 astronomical units (1 AU equals the Earth-Sun distance) and might have been able to measure the distances of stars out to 195 light-years. I say “might” because the vidicon cameras had a fairly narrow dynamic range and problems with distortion. In the words of a colleague at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, who provided me with most of this information, “It would’ve been really tough to do.”

Contrast this with modern CCD ground-based parallax measurements, or those made by the Hipparcos satellite. Using these methods, astronomers can measure parallaxes as small as 0.001″, which allows them to determine stellar distances out to 3,260 light-years. Theoretically, this is more than 15 times better than we could have done with Voyager.

There’s no reason in principal that interplanetary spacecraft can’t be used to measure stellar distances, provided they’re equipped to do so. A while back there was some discussion of sending two identical spacecraft in opposite directions from Earth to do exactly this. The concept didn’t get far, in part because parallax measurements don’t possess a big “glamour factor.” As for the Voyagers, their cameras have been turned off and key camera-control software has been deleted. Their potential for providing such data has ended. — BILL COOKE, MARSHALL SPACE FLIGHT CENTER, HUNTSVILLE, ALABAMA

No, but it was considered. The reason parallax measurements weren’t taken with Voyager or any other interplanetary spacecraft is simply that astronomers can do better from the ground or with dedicated satellites like Hipparcos in low Earth orbit.