The conclusion is based on Herschel’s observations of two patches of sky, each about a third of the size of the Full Moon. It’s like looking through a keyhole across the universe — Herschel has seen more than a thousand galaxies at a variety of distances from the Earth, spanning 80 percent of the age of the cosmos. These observations are unique because Herschel can study a wide range of infrared light and reveal a more complete picture of star birth than ever seen before.

It has been known for some years that the rate of star formation peaked in the early universe about 10 billion years ago. Back then, some galaxies were forming stars 10 or even 100 times more vigorously than what is happening in our galaxy today.

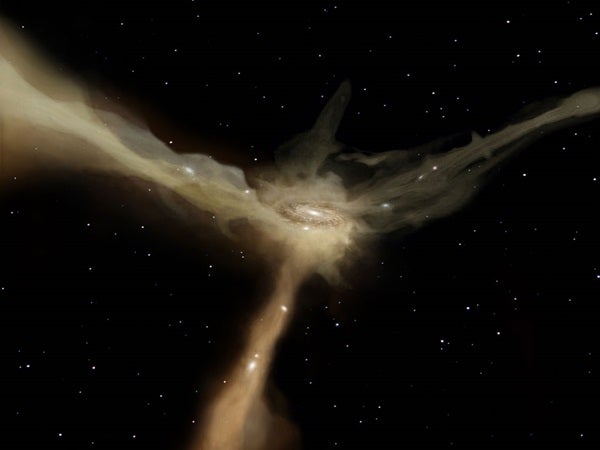

In the nearby, present-day universe, such high birth rates are rare and always seem to be triggered by galaxies colliding with each other. So, astronomers had assumed that this was true throughout history. Herschel now shows that this is not the case by looking at galaxies that are far away and thus seen as they were billions of years ago.

David Elbaz from CEA Saclay, France, and collaborators have analyzed the Herschel data and find that galaxy collisions played only a minor role in triggering star births in the past, even though some young galaxies were creating stars at furious rates.

By comparing the amount of infrared light released at different wavelengths by these galaxies, the team has shown that the star birth rate depends on the quantity of gas they contain, not whether they are colliding.

Gas is the raw building material for stars, and this work reveals a simple link — the more gas a galaxy contains, the more stars are born. “It’s only in those galaxies that do not already have a lot of gas that collisions are needed to provide the gas and trigger high rates of star formation,” said Elbaz. This applies to today’s galaxies because, after forming stars for more than 10 billion years, they have used up most of their gaseous raw material.

The research paints a much more stately picture of star births than before, with most galaxies sitting in space, growing slowly and naturally from the gas they attract from their surroundings.

“Herschel was conceived to study the history of star formation across cosmic time”, said Göran Pilbratt from ESA. “These new observations now change our perception of the history of the universe.”

The conclusion is based on Herschel’s observations of two patches of sky, each about a third of the size of the Full Moon. It’s like looking through a keyhole across the universe — Herschel has seen more than a thousand galaxies at a variety of distances from the Earth, spanning 80 percent of the age of the cosmos. These observations are unique because Herschel can study a wide range of infrared light and reveal a more complete picture of star birth than ever seen before.

It has been known for some years that the rate of star formation peaked in the early universe about 10 billion years ago. Back then, some galaxies were forming stars 10 or even 100 times more vigorously than what is happening in our galaxy today.

In the nearby, present-day universe, such high birth rates are rare and always seem to be triggered by galaxies colliding with each other. So, astronomers had assumed that this was true throughout history. Herschel now shows that this is not the case by looking at galaxies that are far away and thus seen as they were billions of years ago.

David Elbaz from CEA Saclay, France, and collaborators have analyzed the Herschel data and find that galaxy collisions played only a minor role in triggering star births in the past, even though some young galaxies were creating stars at furious rates.

By comparing the amount of infrared light released at different wavelengths by these galaxies, the team has shown that the star birth rate depends on the quantity of gas they contain, not whether they are colliding.

Gas is the raw building material for stars, and this work reveals a simple link — the more gas a galaxy contains, the more stars are born. “It’s only in those galaxies that do not already have a lot of gas that collisions are needed to provide the gas and trigger high rates of star formation,” said Elbaz. This applies to today’s galaxies because, after forming stars for more than 10 billion years, they have used up most of their gaseous raw material.

The research paints a much more stately picture of star births than before, with most galaxies sitting in space, growing slowly and naturally from the gas they attract from their surroundings.

“Herschel was conceived to study the history of star formation across cosmic time”, said Göran Pilbratt from ESA. “These new observations now change our perception of the history of the universe.”