Owing to the lens magnification, the faint background object becomes visible as a ring-like structure around the lensing foreground radio galaxy, seen well on an image made with one of the two 10-meter Keck telescopes on Hawaii.

Led by Martin Haas of Bochum University, Germany, the research started as rather simple observations with the Herschel Space Observatory of a sample of distant radio galaxies. It rapidly grew into a project where crucial supplementary observations demonstrated the unique character of this cosmic lens.

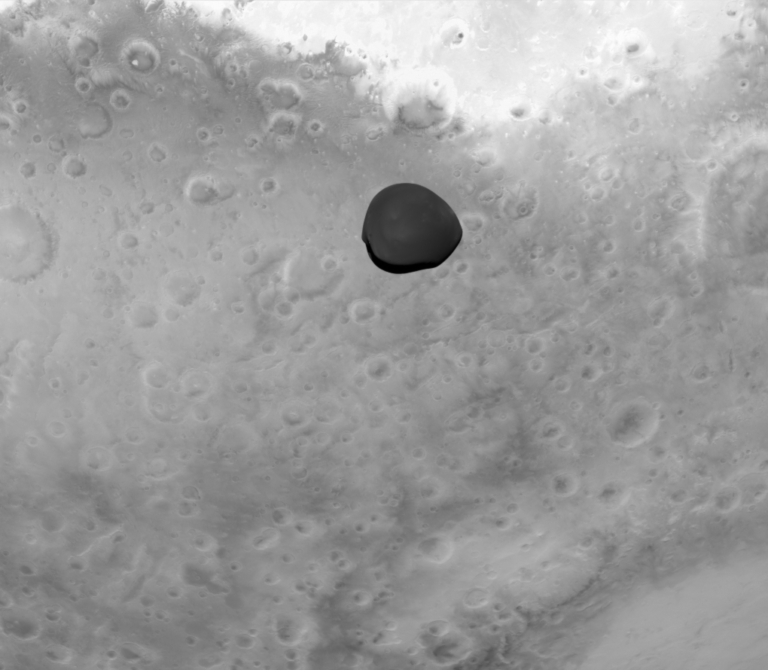

While formally the Herschel Space Observatory did not discover this gravitational lens, it was the breakthrough Herschel performance that allowed the astronomers to measure the far-infrared emission of 3C 220.3, which in turn made them suspicious about its origin. The original target, the massive radio galaxy, emitted simply too much far-infrared radiation. Additional observations, with optical and radio telescopes, subsequently demonstrated unambiguously the cosmic lens effect of the radio galaxy, making the dark background object visible in the far-infrared.

Astronomers have known of the cosmic gravitational lens phenomenon since 1979, although the light bending of distant stars by the Sun was already observed in 1919. Calculations by Einstein in 1912 predicted the existence of such cosmic lenses.

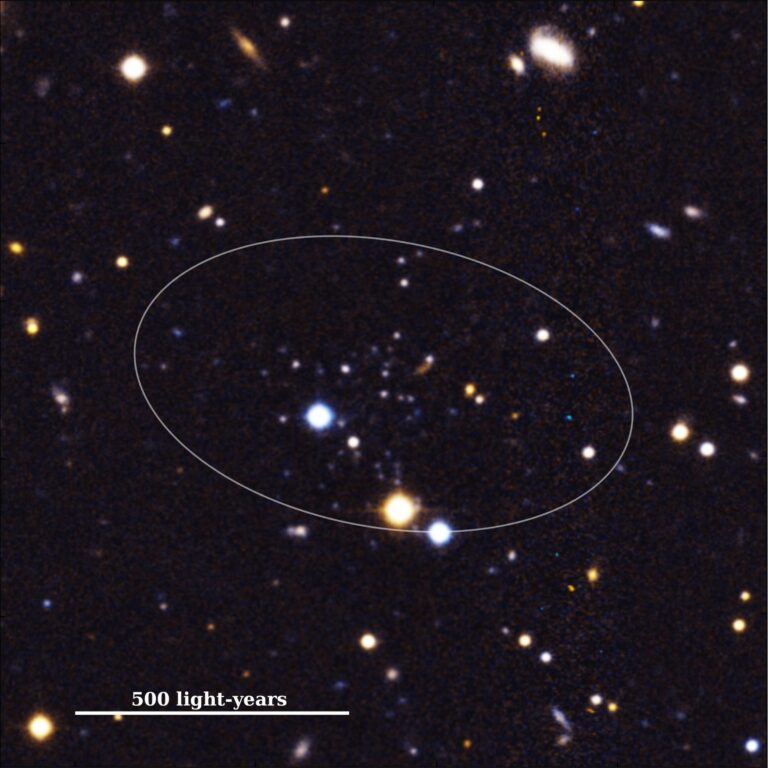

Gravitational lenses allow astronomers to investigate the properties of both the very distant lens and the even more distant object, a galaxy in the process of formation. Modeling of the geometry of the lensing situation for instance demonstrated that the lensing galaxy which hosts the radio source contains an unexpectedly low fraction of mysterious dark matter compared with that predicted for large radio galaxies.