Much like quiet, middle-aged baby boomers peacefully residing in some of the world’s largest cities, families of some galaxies also have a hidden wild youth that they only now are revealing for the first time, according to research by astronomers at Texas A&M University.

In ongoing observations of one of the universe’s earliest, distant cluster of galaxies using NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope, an international team of researchers has discovered that a significant fraction of those ancient galaxies are still actively forming stars.

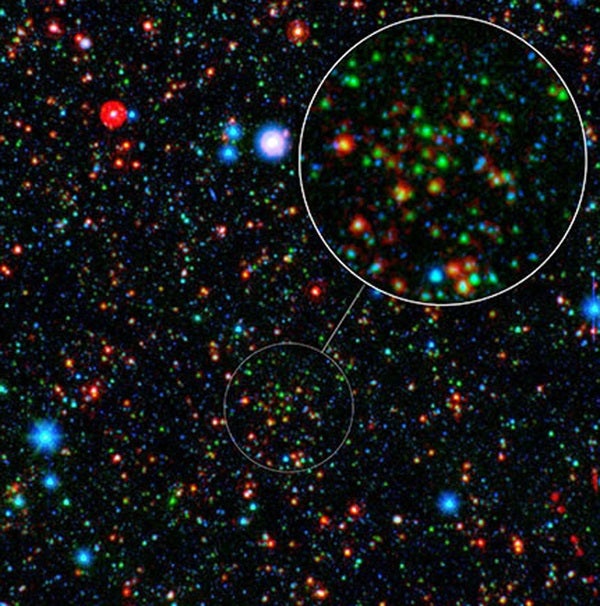

Kim-Vy Tran from Texas A&M University and her team have spent the past 4 months analyzing images taken from the Multiband Imaging Photometer for Spitzer (MIPS), essentially looking back in time nearly 10 billion years at a high-redshift cluster known as CLG J02182-05102. Months after discovering the cluster and the fact that it is shockingly “modern” in its appearance and size despite being observed just 4 billion years after the Big Bang, scientists were able to determine that the galaxy cluster produces hundreds to thousands of new stars every year, a higher birthrate than what is present in nearby galaxies.

What is particularly striking, according to Tran, is the fact that the stellar birth rate is higher in the cluster’s center than at the cluster’s edges, the exact opposite of what happens in our local portion of the universe where the cores of galaxy clusters are known to be galactic graveyards full of massive elliptical galaxies composed of old stars.

“A well-established hallmark of galaxy evolution in action is how the fraction of star-forming galaxies decreases with increasing galaxy density,” said Tran. “In other words, there are more star-forming galaxies in the field than in the crowded cores of galaxy clusters. However, in our cluster, we find many galaxies with star-formation rates comparable to their cousins in the lower-density field environment.”

Exactly why this star power increases as galaxies become more crowded remains a mystery. Tran thinks the densely populated surroundings could lead to galaxies triggering activity in one another, or that all galaxies were extremely active when the universe was young.

The group’s discovery holds potentially compelling implications that could ultimately reveal more about how such massive galaxies form. Observations of nearby galaxy clusters confirm that they are made of stars that are at least 8 to 10 billion years old, which means that CLG J02182-05102 is nearing the end of its hyperactive star-building period.

Now that they have pinpointed the epoch when galaxy clusters are making the last of their stars, astronomers can focus on understanding why massive assemblies of galaxies transition from very active to passive. Identifying how long it takes for galaxies in clusters to build up their stellar mass, as well as the time at which they stop, provides strong constraints for how these massive galaxies form.

“Our study shows that by looking farther into the distant universe, we have revealed the missing link between the active galaxies and the quiescent behemoths that live in the local universe,” Tran said. “Our discovery indicates that future studies of galaxy clusters in this redshift range should be particularly fruitful for understanding how these massive galaxies form as a function of their environment.”

Casey Papovich from Texas A&M University first identified the galaxy cluster CLG J02182-05102 in May. The collection of roughly 60 galaxies is observed just 4 billion years after the Big Bang, making it the earliest cluster of galaxies detected. However, the scientists were struck not by its age, but by its astoundingly modern appearance — a huge, red collection of galaxies typical in only local clusters.

The fact that Tran’s team was able to see these active galaxies so far back in time is only the preface to what they expect eventually to learn about these clusters. Tran will continue to lead an international collaboration with Papovich and other researchers to examine these clusters more thoroughly and hopefully to understand why they are still so energetic.

“We will analyze new observations scheduled to be taken with the Hubble Space Telescope and Herschel Space Telescope to study these galaxies more carefully to understand why they are so active,” Tran said. “We will also start looking at several more distant galaxy clusters to see if we find similar behavior.”