The heat in the atmosphere of Venus, induced from a strong greenhouse warming, might actually have a cooling effect on the planet’s interior. This counter-intuitive theory is based on calculations from a new model presented at the European Planetary Science Congress (EPSC) in Rome, Italy, September 21.

“For some decades, we’ve known that the large amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of Venus cause the extreme heat we observe presently,” said Lena Noack from the German Aerospace Center in Berlin.

“The carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases that are responsible for the high temperatures were blown into the atmosphere by thousands of volcanoes in the past,” said Noack. “The permanent heat — today we measure almost 470° Celsius (880° Fahrenheit) globally on Venus — might even have been much higher in the past and, in a runaway cycle, led to even more volcanism. But at a certain point, this process turned on its head. The high temperatures caused a partial mobilization of the venusian crust, leading to an efficient cooling of the mantle, and the volcanism strongly decreased. This resulted in lower surface temperatures, rather comparable to today’s temperature on Venus, and the mobilization of the surface stopped.”

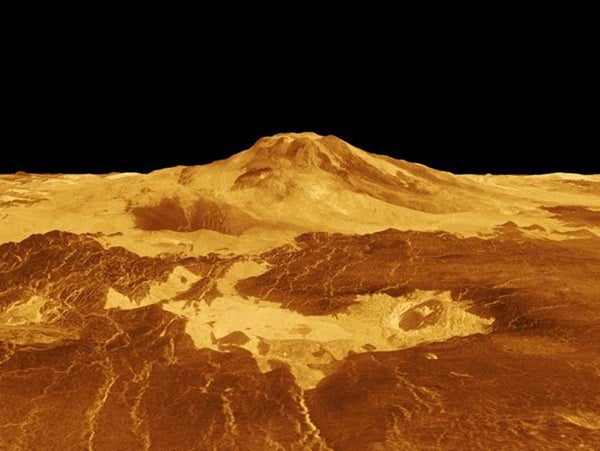

The source of the magma, or molten rocky material, and the volcanic gases lies deep in the mantle of Venus. The decay of radioactive elements, inherited from the building blocks of the solar system’s planets, and the heat stored in the interior from planet formation produced enough heat to generate partial melts of silicate-, iron-, and magnesium-rich magma in the upper mantle. Molten rock has more volume and is lighter than the surrounding solid rock of identical composition. The magma therefore can rise upward and eventually penetrate through the rigid crust in volcanic vents, spreading lava over the surface and blowing gases into the atmosphere, mostly greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide (CO2), water vapor (H2O) and sulphur dioxide (SO2).

However, the more greenhouse gases, the hotter the atmosphere — possibly leading to even more volcanism. To find out if this runaway process would end in a red-hot Venus, Noack and Doris Breuer, also from the German Aerospace Center, calculated for the first time a model where the hot atmosphere is coupled to a 3-D model of the planet’s interior. Unlike here on Earth, the high temperatures have a much bigger effect at the interface with the rocky surface, heating it up to a large extent.

“Interestingly, due to the rising surface temperatures, the surface is mobilized and the insulating effect of the crust diminishes,” said Noack. “The mantle of Venus loses much of its thermal energy to the outside. It’s a little bit like lifting the lid on the mantle — the interior of Venus suddenly cools very efficiently, and the rate of volcanism ceases. Our model shows that after that hot era of volcanism, the slow-down of volcanism leads to a strong decrease of the temperatures in the atmosphere.”

The calculations of the geophysicists yield another interesting result: The process of volcanic resurfacing takes place at different places at different times. When the atmosphere cools, the mobilization of the surface stops. However, there are still a few active volcanoes that resurface some spots with lava flows. Some volcanoes might be active even today, which fits recent results from the European Space Agency’s Venus Express mission. This detected “hot spots,” or unusual high surface temperatures at volcanoes previously thought to be extinct. So far no “smoking gun,” or active volcano, has been identified on Venus, but it seems not unlikely that Venus Express or future space probes will detect the first active volcano on Earth’s neighbor.