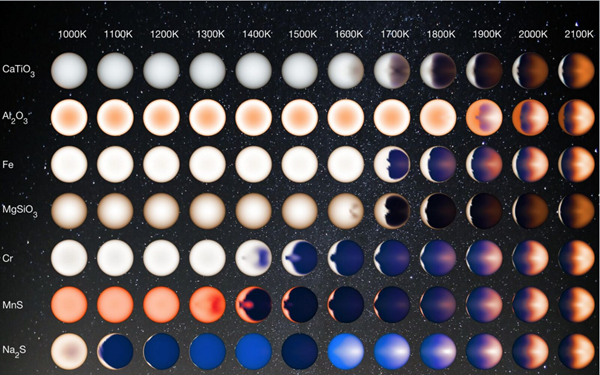

The hottest gas giants shine in a startling array of hues. New research suggests that at least some of them sport clouds with a distinctive orange glow, while others with enormous dirt clouds may shine a deep blue. The different colors come from different types of clouds that form depending on how hot the planet grows.

Known as hot Jupiters, the massive gas giants orbiting their star in days or even hours look like nothing seen in our solar system. Combining studies from NASA’s Spitzer spacecraft with the initial observations from the planet-hunting Kepler mission, scientists noticed something peculiar. The warmer planets grew brighter after they ducked behind their star, while cooler ones were brighter after they emerged on the other side.

The new findings suggest that only clouds of manganese sulfide, a crystals found in terrestrial rocks, and silicates, which make up dirt and rock on Earth, could create the most noticeable signals identified by Kepler, providing the first correlation between a hot Jupiter’s temperature and cloud coverage.

“The part of the atmosphere we can see also sees the strong difference in irradiation between day and night,” Vivien Parmentier, an exoplanet scientist at the University of Arizona in Tuscan, said by email. “This creates strong winds that can efficiently support the weight of the clouds [and] they just constantly hover in the atmosphere.”

Parmentier and his colleagues simulated the variety of clouds that could form on hot Jupiters in the universe. After modeling the types of clouds that could form under a variety of temperatures, they found that light streaming from the planet is based more on the material making up the clouds than the size of the particles.

The hottest worlds could host clouds of silicate particles, common in sand and rock on Earth, which would give their worlds a brownish cast. Silicate clouds are common in brown dwarfs, enormous bodies not quite large enough to kick off the hydrogen fusion that defines stars.

The strange dips of the cooler worlds could be explained by clouds of manganese sulfide. Neither Kepler nor Spitzer observes the world in visible light, so the researchers relied on models to determine that the manganese sulfide clouds would appear orange to human explorers.

“We have never seen manganese sulfide clouds in the solar system,” Parmentier said. “Actually, we have never seen them before, [unlike] the silicate clouds that are found in brown dwarfs.” That’s because the lower gravity and efficient atmosphere mixing of the hot Jupiters means they are better at forming clouds than the larger brown dwarfs.

According to Parmentier, blue clouds show up on worlds where the clouds are not too bright. As high temperatures burn away the clouds, the sky glows a deep blue. Although the same process causes the color, the cloudless face would be a darker shade than Earth’s own sky.

The close orbits of hot Jupiters keeps one face permanently facing its star. As the heat moves around the atmosphere, it causes the trailing edge of the day side to shine brighter, creating the unusual signals detected by the spacecraft. As the temperatures rise, the clouds cover less and less of the day side.

“For the very hot planets, the red color that appears on the east is due to the thermal emission of the planet,” Parmentier said.

“The planet is glowing and we can see it.”

The research is published in The Astrophysical Journal.