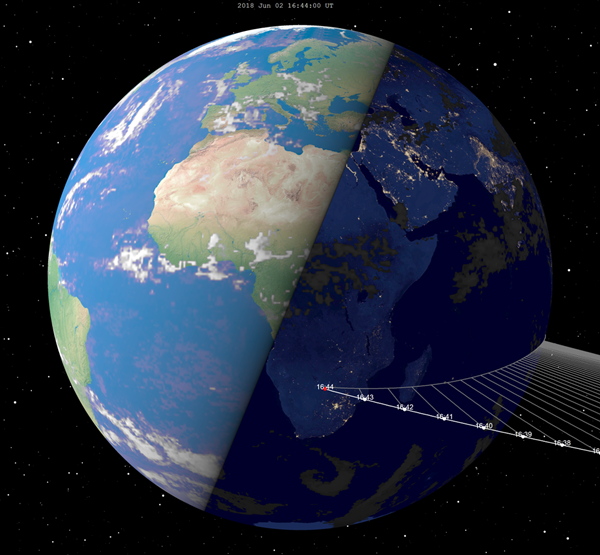

Early last month, an asteroid invaded our personal planetary space, brilliantly illuminating night skies across Southern Africa. Officially dubbed 2018 LA, this small asteroid entered Earth’s atmosphere on June 2, flying in at an impressive 38,000 mph (61,000 km/h). Richard Kowalski of the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS) spotted the new asteroid nearly 8 hours before its impact with our atmosphere, allowing scientists to determine possible landing sites. 2018 LA’s final destination was near the Botswana border, where surveillance cameras captured video of the meteor (the name for an asteroid once it has entered the atmosphere) as it exploded 30 miles (50 km) above ground. Scientists eagerly looked for any surviving space rocks that reached the ground, a.k.a. meteorites, and finally found the first piece on June 23.

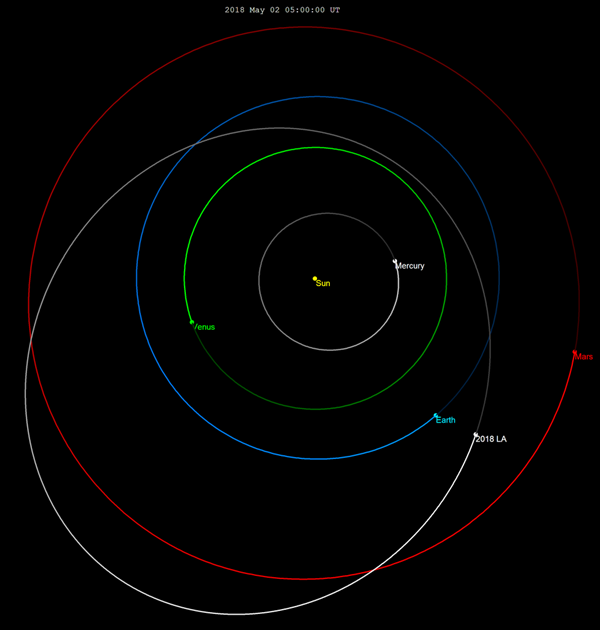

This asteroid was only the third to be spotted and monitored before reaching Earth, all of which were incidentally discovered by Richard Kowalski. Before disintegrating in our atmosphere, 2018 LA belonged to the Apollo group of near-Earth asteroids. Near-Earth asteroids are a type of near-Earth object (NEO) that travel within 1.3 AU of our Sun (1 AU, or astronomical unit, is the average Earth-Sun distance of 93 million miles [150 million kilometers]).

NEOs can also be classified as potentially hazardous objects (PHOs) if they have characteristics that, upon potential impact with Earth, could cause significant destruction. If an asteroid is greater than about 140 m (460 ft) in diameter and approaches Earth’s orbit within 4,650,000 miles (7,480,000 km), only then is it classified as a PHO. Fortunately, 2018 LA was not large enough to be considered a PHO, even though it was just outside the Moon’s orbit (about 239,000 miles [384,000 km]) when discovered.

Impact of 2018 LA

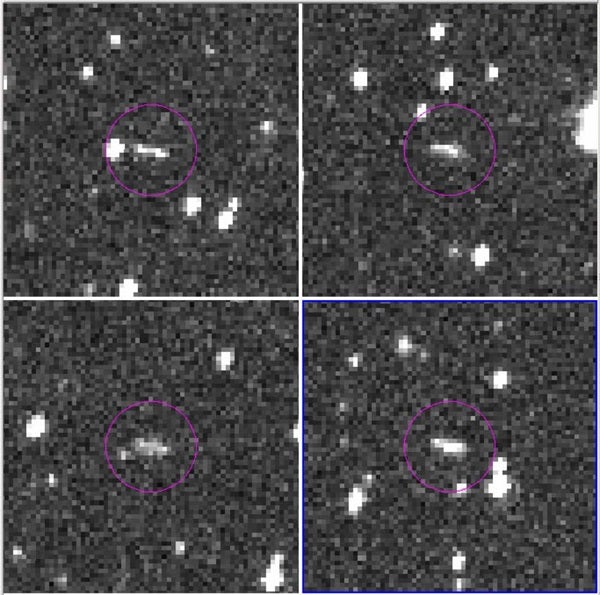

2018 LA was initially discovered as a streak traveling quickly across a series of exposures taken with the Mt. Lemmon Survey (part of CSS) telescope in Arizona. This apparent motion in the images revealed its extreme proximity to Earth. Per protocol, 2018 LA data were sent over to the Minor Planet Center, and in turn to NASA’s Scout program of the Center for Near Earth Object Studies (CNEOS), which both calculated high probability of the asteroid reaching Earth. In addition, Project Pluto’s Bill Gray calculated an 82 percent chance of impact, with the westernmost possible landing site at the border of South Africa and Botswana. (You can also find 2018 LA’s ephemeris in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s Small-Body Database here.)

However, these trajectories placed the most likely impact site somewhere in the Indian Ocean, not Africa, leading scientists to question whether the object that lit up the skies was indeed 2018 LA. Follow-up observations of the object from the ATLAS telescope on Maunaloa came in after the event, adding significant information to aid in modeling the asteroid’s path. The ATLAS observations confirmed that the asteroid was bound for impact, and that the fireball (a meteor appearing brighter than the planet Venus) reported in Southern Africa must have been 2018 LA.

Tracing asteroid trajectories

All of the steps taken in the case of 2018 LA represent standard procedure for most asteroid hunting projects. First comes the discovery, and luckily there are plenty of surveys dedicated to identifying NEOs: in addition to CSS, telescopic surveys such as Pan-STARRS and NEOWISE contribute asteroid findings regularly. For example, the NEOWISE space mission has discovered hundreds of new NEOs since 2013. These NASA funded projects continuously scan the sky for rapidly moving objects like 2018 LA.

Once an asteroid has been discovered, scientists want to know its orbital properties as well as its size. This information will help astronomers better classify the object — including whether or not it is a hazard.

The size of an asteroid can be tricky to determine. Before they can accurately report a diameter, astronomers must know the asteroid’s magnitude (brightness) and distance, at the very least (usually, they also need an albedo, which measures the reflectivity of an object’s surface). Scientists use a variety of different methods to measure the distance to solar system objects, where precise distance at any given time comes from modeling the asteroid’s path. Knowing its distance and magnitude, astronomers used telescope observations to estimate that 2018 LA was about 2 to 5 m (6.6 to 16.4 ft) across. Luckily, this is not large enough to be hazardous.

In the case of 2018 LA, its small size was confirmed using infrasound — sound waves with frequencies below the threshold of human hearing. As 2018 LA burst into pieces, it created infrasound waves equivalent to the explosion of 300-500 tons of TNT. Kowalski states that this explosion was a consequence of the meteor slowing down so rapidly in the atmosphere that its back traveled faster than its front. The resulting signal was picked up by a CTBTO infrasound station in South Africa and corresponded to the expected explosion of a 2-meter (6.6 ft) asteroid.

You may be more concerned with whether a meteor is going to hit your house than you are about its relative size. Fair enough — in that case, asteroid trajectory models need little more than telescopic observations to plot a path. A minimum of three observations will typically do the trick, from which scientists gather the object’s orbital direction as its position changes on the sky. With additional information about the observer and the time of observations, orbital parameters can be obtained and a path determined. The more observations that scientists have, the better the model will be.

The hunt

Typically, modeling an asteroid’s orbit is the end of the road, since researchers rarely observe an asteroid both in space and again while plummeting to Earth as a meteor; but not so for 2018 LA. After 2018 LA’s explosion, a group of astronomers and geoscientists teamed up in search for fresh meteorites from the fallen asteroid. First, they gathered all video footage of the fireball. This helped SETI and Finnish Fireball Network scientists to calculate the most likely location for a meteorite discovery. Then, they went on an old-fashioned hunt, which landed them in the Botswana’s Central Kalahari Game Reserve.

“The challenge was to search for a meteorite in 200 square kilometers of uncharted wild in a park teeming with elephants, lions and snakes,” said Prof. Alexander Proyer of the Botswana International University of Science and Technology (BUIST) in a SETI press release. Talk about risking your life for science. Thankfully, the Reserve sent its rangers on the expedition to help fend off any predators.

After five days of searching in the wilderness, history was made when a BUIST student noticed the first meteorite. This is only the second time that a meteorite has been recovered from an asteroid first spotted in space. The prized piece of 2018 LA will remain in Botswana for research and display.

If you happen to be in Botswana, keep checking the ground for those space rock souvenirs. Analysis of any meteor remnants could shed light on 2018 LA’s history. If you’re not, keep your eyes on the sky and watch out for fireballs. If you happen to see one, report the incident to the American Meteor Society, which tracks meteor reports for amateurs and professionals interested in asteroid and meteor astronomy.