In the summer of 1863, the U.S. was in the middle of its greatest-ever crisis. A bloody civil war between the Southern Confederacy and the federal government had created hundreds of thousands of casualties, and to many, no end appeared to be in sight. By July of that year, however, things finally seemed to be brightening slightly for the hopes of a united country. Decisive victories for the Union at Gettysburg and Vicksburg gave the first glimmers of foresight that the war would eventually cease and that healing would begin.

Seven weeks after the Battle of Gettysburg, the nation’s leader, Abraham Lincoln, paid an unusual Washington, D.C., visit. Accompanied by his young private secretary John Hay, Lincoln made an unannounced journey to the U.S. Naval Observatory to indulge his interest in astronomy and to seek a brief reprieve from the war. In those days, the observatory was located at 23rd and E streets, about three blocks north of what is now the Lincoln Memorial site. (This area, called Foggy Bottom due to the frequent haze and fog that rolled off the Potomac, wasn’t the best site for a telescope, and eventually the observatory would move.)

On the night of Aug. 22, 1863, the observatory was manned by a young astronomer, Asaph Hall. Fourteen years later, Hall would discover the two moons of Mars, but on that evening, he was an unknown 33-year-old researcher. Lincoln and Hay arrived and introduced themselves — as if Lincoln needed to be introduced. The group climbed up a wooden ladder to the dome where the observatory’s 9.6-inch refractor was located. There they observed the Moon and the star Arcturus.

In the 1980s, I was privileged to visit the historic site of the Old Naval Observatory, courtesy of Jan Herman, the observatory’s former historian and a contributor to Astronomy. Climbing up the same wooden steps Lincoln had used to enter the dome gave me an ethereal feeling of the past, the present, and the universe, all meeting at one point.

Omens of victory and defeat

Not all participants of the Civil War sought to contemplate the meaning of the cosmos as Abraham Lincoln did, but some viewed certain events as a beacon of hope — or demise.

On May 13, 1861, an observer in New South Wales, Australia, found what came to be called the Great Comet of 1861. By midsummer, the comet had moved so that it was visible in the Northern Hemisphere sky and, according to astronomer Horace Tuttle, sported a tail 106° long.

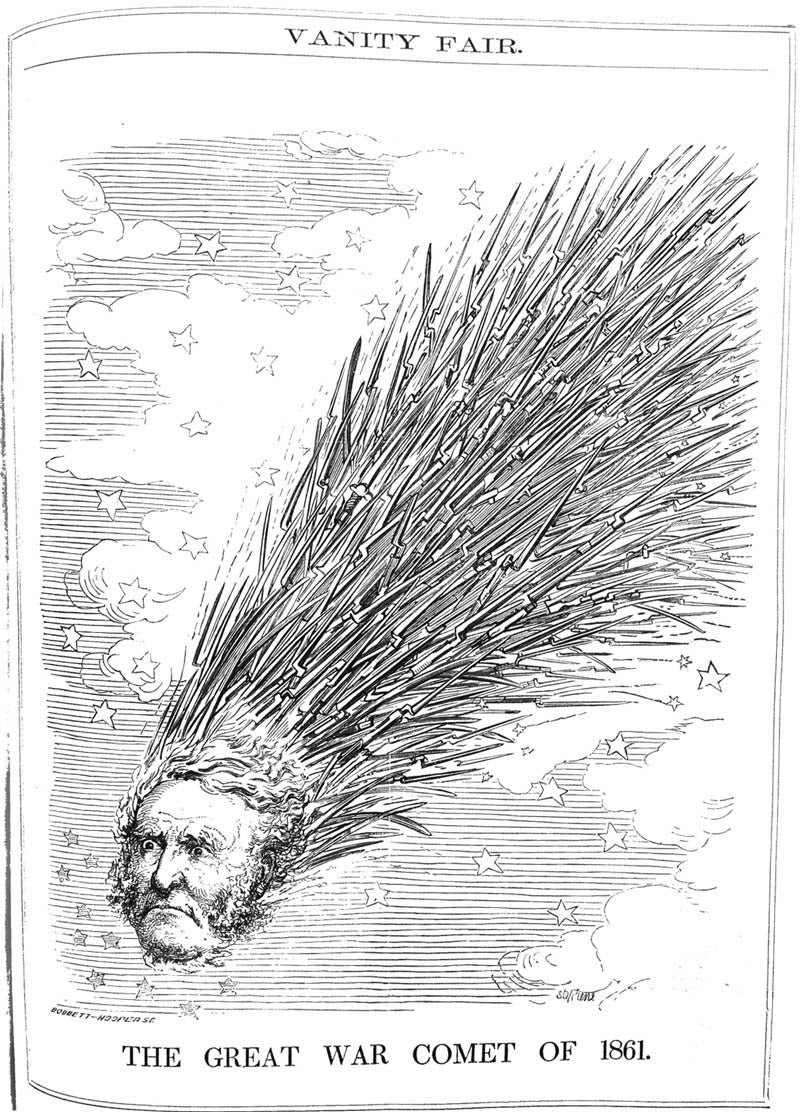

The comet caused a press sensation. The evening spectacle came to be called The War Comet, and the editors of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle posed a question to their readers: “What means this visit — peace or war?” Vanity Fair published a cartoon showing Lt. Gen. Winfield Scott, the senior general of the Union army, as the comet’s head and a slew of bayonets comprising the tail.

During this time, Charles Johnson, a private in the 9th New York Infantry, wrote in his diary, “The comet is now tired of his visit to these regions of space, or disgusted it may be with the appearance of things on this side of the planet, for he is now leaving in seemingly greater haste than he came, with his tail between his legs, for the unknown regions out yonder.”

The Great Comet of 1861 faded during the week of the First Battle of Bull Run, leading to vast speculation on that meaning. But comets were not done with the war. In 1862, Tuttle discovered another comet that would rise to significant brightness. Astronomer Lewis Swift had also spotted the comet, which became known as Swift-Tuttle. When that comet faded in September 1862, many attached its significance — one way or another — to the battle of Antietam, a substantial Union victory. Decades later, astronomers would identify this comet as the source of the Perseid meteor shower.

In December 1862, during the battle of Fredericksburg in Virginia, a different kind of celestial omen made its appearance. After a slow and discouraging lack of progress during the war’s first two years, Lincoln assigned Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside to command the Army of the Potomac, the principal Union army in the east. Burnside faced Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee at Fredericksburg and sent repeated frontal attacks into the Rebel works, ending in a Union disaster.

Following the battle, as the cries of wounded filled the icy December air, an aurora appeared in the sky, visible to many thousands of soldiers on both sides. “A brilliant aurora illuminated the night and much facilitated the work upon the entrenchments,” wrote Confederate Col. Edward Porter Alexander.

The light show was taken as an omen of victory by Southerners, who had inflicted heavy losses on the Yankee troops. And, of course, many Union soldiers saw it as an omen of doom. Citizens in Fredericksburg, in Charlottesville, and all over the region remarked on the unusual aurora. “Oh, child, it was a terrible omen,” wrote Elizabeth Lyle Saxon in her 1905 reminiscences, quoting an elderly woman’s words to her. “Such lights never burn, save for kings’ and heroes’ deaths.” A writer for the Richmond Daily Dispatch proposed the crimson columns of light represented “the blood of those martyrs who had offered their lives as a sacrifice to their native land.”

By the light of the Moon

In the following months, a significant event rocked the command structure of the Confederate Army. The battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863 was yet another huge win for the Confederacy, following the triumph at Fredericksburg. But in the action, the Southern general Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, was accidentally and mortally wounded by other Confederate troops.

Recently, astronomers have shed some light — or rather some moonlight — onto why the events of that night led to Jackson’s death. As the Sun faded on that fateful day at Chancellorsville, Jackson pressed his men forward. Stonewall’s flank attack crushed a portion of the Union force, held by Maj. Gen. Oliver Howard’s 11th Corps. Jackson rode out under moonlight to the Plank Road, assessing the situation and determining the feasibility of a night attack by the light of the Full Moon. Soldiers in the 18th North Carolina Infantry believed the small group of riders, including Jackson, were Union cavalry and opened fire. Jackson was hit with three bullets, including in his left arm, which had to be amputated later that night. Confederate doctors attempted to transport him to Richmond for follow-up care, but he developed pneumonia and died eight days later.

In 2013, a group led by Don Olson of Texas State University determined that, based on astronomical research and battle maps, Stonewall and his party would have been viewed as a group of dark silhouettes using the light of the Moon, which sat at a low 25° above the horizon, as their guide. Their positions ultimately obscured their identities, resulting in the soldiers mistakenly opening fire.

The astronomer general

North of the Mason-Dixon Line, another prominent figure was strongly associated with the night sky.

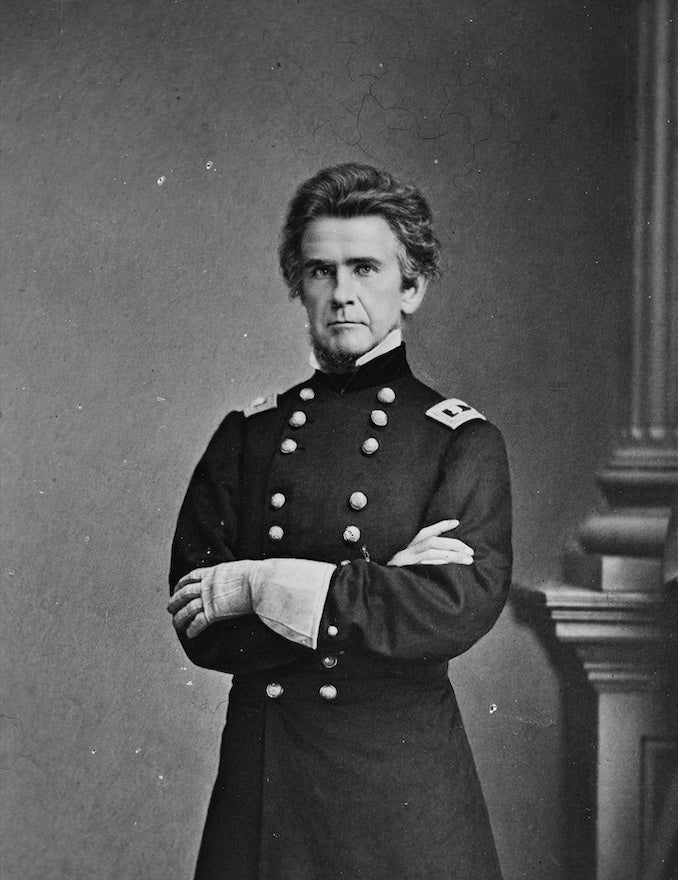

On the Union side, a well-known astronomer became one of the most prominent general officers in the western theater. Ormsby Mitchel had been born in Kentucky but grew up in Lebanon, Ohio, and was a classmate of Robert E. Lee at West Point. During his career, he helped establish the U.S. Naval Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. Mitchel also studied the double star Nu (ν) Scorpii and found in 1846 that the fainter of the two stars was also a close double.

After West Point, Mitchel became a professor of mathematics at the military academy, but then returned to Ohio, became a lawyer and engineer, and began a professorship at Cincinnati College. He organized the Cincinnati Astronomical Society and became an early popularizer of the subject. In 1859, Mitchel moved to the Dudley Observatory in New York. But in 1861, as the war rapidly approached, he returned to his military roots at the age of 51.

Commissioned a brigadier general, Mitchel first supervised defenses around Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky. In 1862, he conspired with a Union spy, James J. Andrews, on a plot that would come to be known as the Great Locomotive Chase. Given the nickname Andrews’ Raiders, they stole the Confederate locomotive The General in northern Georgia, intent on disrupting the important railway between Atlanta and Chattanooga. The plan that Mitchel ordered but did not participate in eventually failed. Many of the raiders were captured and eight were hanged by the Confederacy, including Andrews himself, while others were able to escape. Afterward, 19 of the living and executed men became the first recipients of the Medal of Honor.

Despite the raid’s failure, Mitchel continued to lead other successful operations throughout the year. By September 1862, he was assigned command of a post in Beaufort, South Carolina, but he contracted yellow fever and died there in October.

A time of discovery

The era in which Mitchel lived and the Civil War occurred not only saw a dramatic upheaval of the U.S. but also witnessed the rise of astrophysics. During this time, a field of simple observing and cataloging transformed into understanding the physical nature of what the universe contains.

Out of a maelstrom of chaos eventually came order, a start down the long road to justice and equality, and the beginnings of an understanding of our larger universe.