Living things could permeate the universe. With at least 25 thousand billion billion star systems out there, it’s an incredible conceit to think Earth is the only planet in the whole universe hosting life. Yet over the history of astronomy, we know of only one planet that hosts life — ours. If we were to find life elsewhere, whether microbes in our solar system or more complex beings farther away, how would we recognize it?

It might not be easy. But there are starting points. “Astrobiologists argue some properties must be universal to life wherever it occurs,” says Alan Longstaff, an astronomer and chemist at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England. First, life is defined as a complex chemical system that uses energy, generates waste, reproduces, and takes part in evolution over time. The successful critters on Earth, and presumably in other places too, exist in huge numbers. They also can replicate themselves successfully enough to survive the rigors of a sometimes hostile environment.

Bringing the universe to your door. We’re excited to announce Astronomy magazine’s new Space and Beyond subscription box – a quarterly adventure, curated with an astronomy-themed collection in every box. Learn More >>.

All known life is carbon-based, Longstaff reminds us. No other chemical element is as adaptive to the variety of reactions carbon can undergo. And, crucially, all life we are familiar with needs liquid water. Water allows biological molecules to interact the right way — that’s why the search for life on planets in the solar system follows the mantra, “Follow the water.”

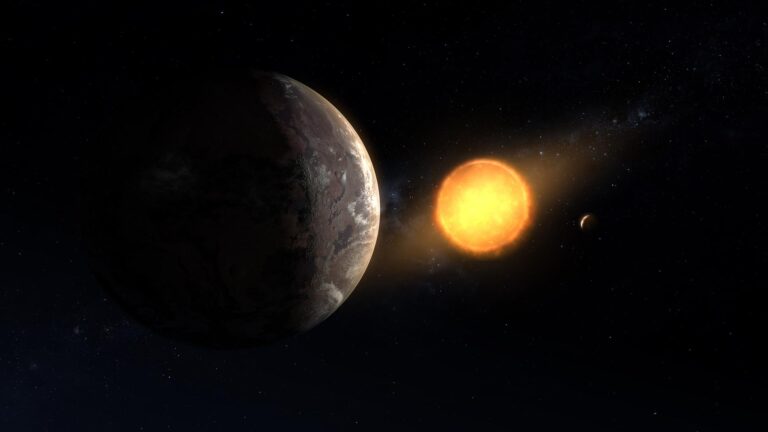

Astronomers already know of more than 2,500 planetary systems, plenty of which are rocky terrestrial worlds like Earth and Mars.

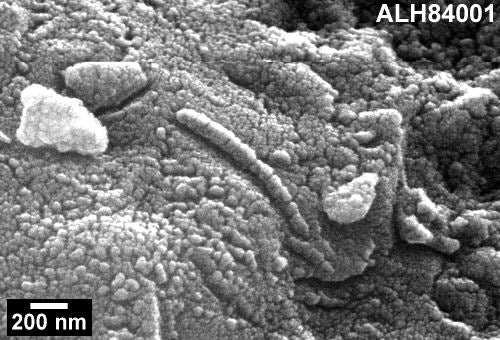

But even with many rocky planets out there, how easy is it to make life? Again, the only example we have is right here on Earth. After our planet’s formation 4.54 billion years ago, life left traces enriched with carbon isotopes in sedimentary rocks. The earliest yet examined, from west Greenland, date to 3.85 billion years ago. That’s the earliest record of life on Earth. Considering a rain of rocks periodically battered Earth’s surface, life probably started and was snuffed out several times before finally taking hold. This suggests life started quickly on Earth, and, therefore, the odds it could start elsewhere, under challenging conditions, are good.

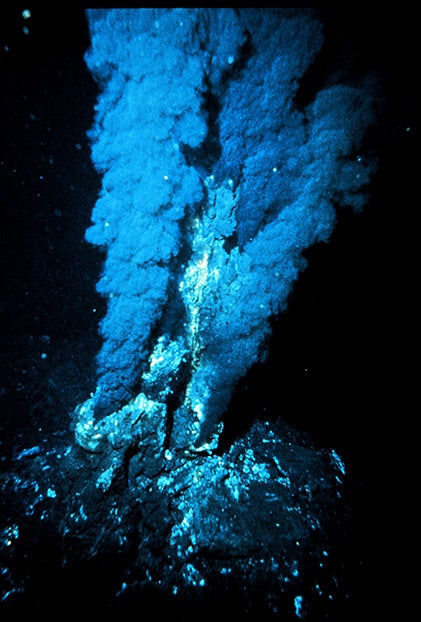

Life can exist in hellish places — and on frozen worlds, too. In recent times, scientists have discovered hydrothermophiles that thrive in high-pressure ocean water as warm as 242° F (117° C). Many species of bacteria exist several miles underneath Earth’s crust, one place that would have been safe during the heavy bombardment period. Conversely, microbial life exists in the pack ice of the Arctic and Antarctic. It, therefore, might thrive in similar conditions on Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

As astronomers discover more and more exoplanets, how will they know which ones to focus on as possible habitats for life? Planetary spectra will give astronomers significant clues. Living things alter their environments through the chemical reactions they undergo while they are alive. These reactions can manifest themselves in planetary spectra as molecules that should not exist unless living creatures are producing them.

Scientists know that Earth’s atmosphere contains oxygen only because photosynthesis creates it faster than it is depleted by other processes, such as iron rocks oxidizing. So detecting an abundance of ozone and methane in a planet’s atmosphere, for example, would be strongly suggestive of living beings on it.

But life will not be found virtually anywhere. Temperatures have to be right, and liquid water probably has to be present. Equilibrium is good: Life doesn’t like wild swings in its environment. Alien life-forms, although they could be radically different than what we know on Earth, will share common characteristics and chemistry. If astronomers do succeed in detecting life elsewhere in the cosmos, one thing is certain: It will be a huge moment for the history of human civilization.