Exoplanets, by definition, exist outside our solar system, orbiting other stars. That means they’re pretty far away. Telescopes, even top-notch ones like Hubble, can’t image anything as small as a planet outside our solar system. Even Neptune, in our own solar system, is a blurry blue ball when viewed from Earth’s orbit.

So planets outside our solar system are practically invisible. However, planets can and do affect their stars in measurable ways, and that’s how astronomers find them.

The two most widely used methods are transits – the blinking method – or Doppler shifting – the wobble method.

Want to learn more about exoplanets and other solar systems? Check out our free downloadable eBook: Our Search for Extrasolar Planets.

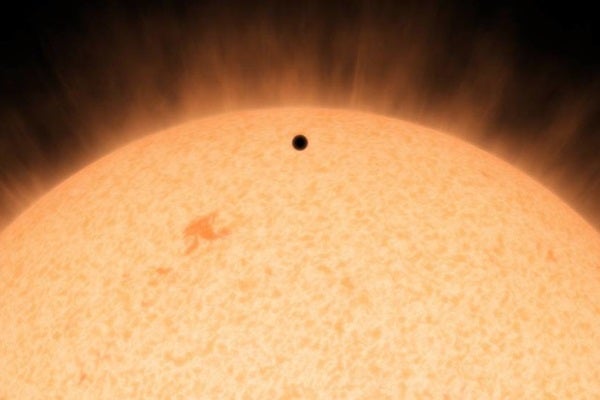

When a planet orbits its star, the planet will sometimes cross between it and Earth. This crossing is called a transit, and when it happens, the planet blocks a bit of the star’s light. It may be well under one percent of the light, but that’s enough for special telescopes to measure. If that star is blinking in a regular, cyclical pattern, that tells astronomers there’s a planet circling it – as well as the size (width) of the planet and how big its orbit is.

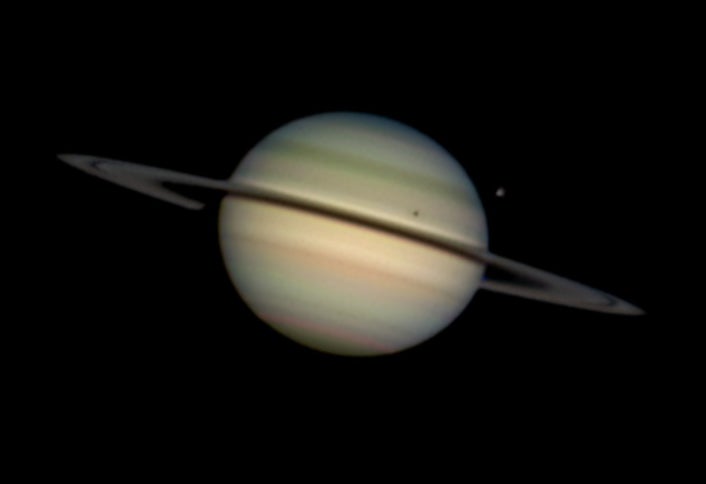

In the wobble method, astronomers rely on the fact that just as stars tug on their planets to keep them in orbit, planets also tug on their stars. So, as a planet circles, its star will wobble back and forth very slightly. This wobble is usually too small to see in an image, but it does show up as a wiggle in the spectrum, or color, of the star. Again, astronomers look for a pattern to that wiggle, which tells them how massive a planet is and how far away it orbits.

Read more: