The neutrino is one of the most common particles in the universe, but you would never know it. In fact, it wasn’t until the 1930s that we even became aware of its existence.

What is a neutrino?

Noting that certain nuclear reactions seemed to be missing a little bit of energy, physicists beginning with Wolfgang Pauli in 1930 suggested that those reactions might create a small, neutral, hidden particle. It was Enrico Fermi who gave the name to these particles in 1934: neutrino, Italian for “little neutral one.”

For decades physicists assumed the neutrino was massless, but now we know it does contain a tiny amount of mass. We don’t know the precise value, but we do know that it’s thousands of times lighter than the electron.

From the core of the Sun to distant supernovae, a variety of high-energy reactions throughout the universe produce a flood of neutrinos. But because they are nearly massless, uncharged, and travel at nearly the speed of light, they rarely interact with other matter and thus remain almost entirely invisible. Right now, trillions of neutrinos are passing through your body every single second — but you’re likely to be hit by only one in your entire lifetime.

Despite their ghostly nature, neutrinos provide unprecedented views into the high-energy cosmos. With neutrinos, we can peer directly into the heart of the Sun, open up a dying star before it explodes, or get a sense of the extreme energies swirling around supermassive black holes.

How to find neutrinos

To detect neutrinos, astronomers have to rely on the weak nuclear force, which is the only way that neutrinos interact with other matter. Through this force, quarks change type or charge, which in turn changes protons into neutrons, and vice versa.

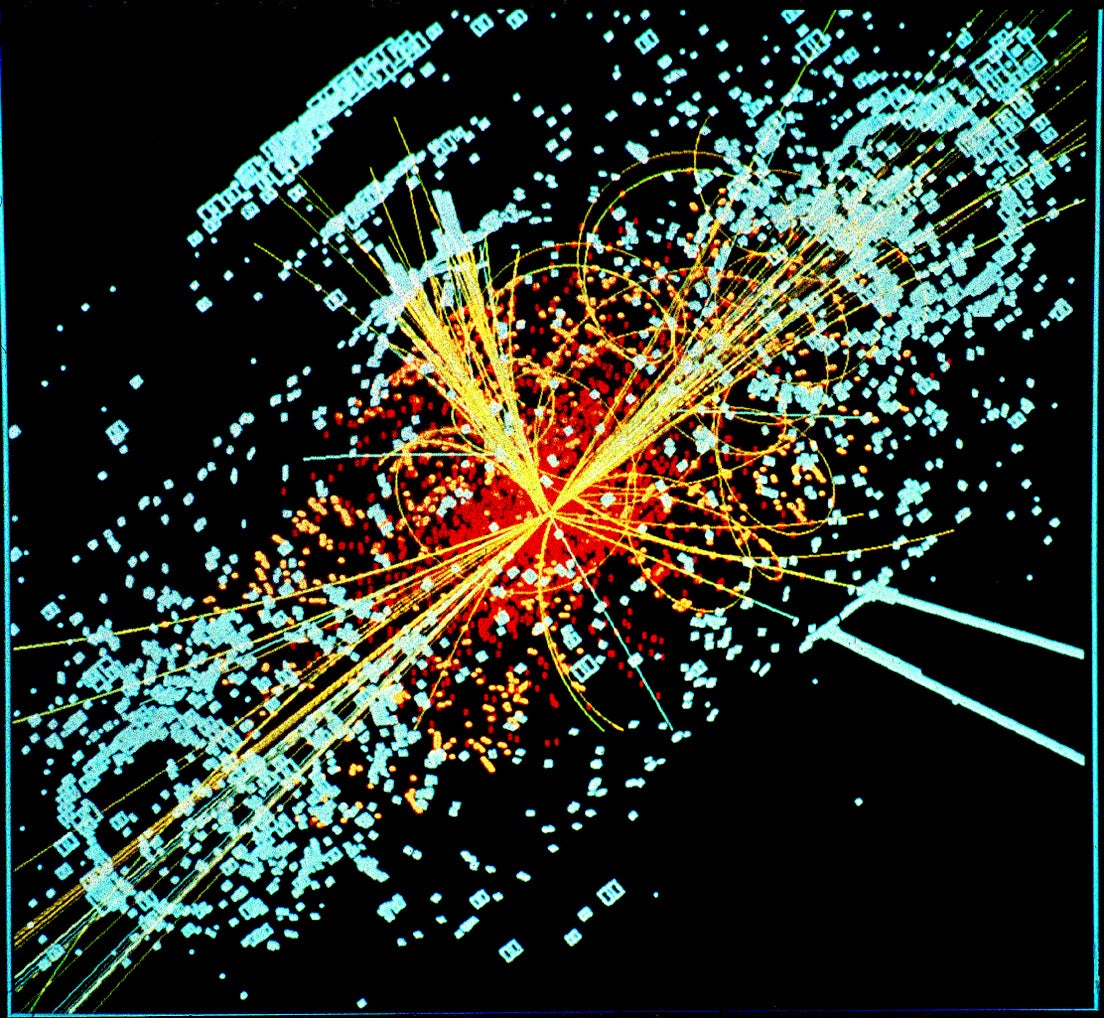

Here’s how this happens: A neutrino will rarely strike an atomic nucleus and produce a muon, a short-lived, massive, electrically charged particle. The muon then goes screaming off in a shower of further subatomic reactions, which are what astronomers look for.

But such collisions are so rare that enormous volumes of target material are needed to create a neutrino telescope. What’s more, astronomers need to place these instruments deep underground or underwater. That’s because neutrinos aren’t the only high-energy particles streaming into our atmosphere. Cosmic rays, which are atomic nuclei (generally protons) traveling close to the speed of light, produce similar effects, and so the telescope needs to be insulated from that unwanted source of contamination.

Neutrino telescopes consist of grids of light detectors called photomultiplier tubes, which are embedded within water or ice. When a neutrino strikes the nucleus of an atom within the target material (i.e., water or ice) and creates a muon, the muon can travel faster than the speed of light in the water or ice. This produces the electromagnetic equivalent of a bow shock from a speeding boat, a bluish light called Cherenkov radiation.

The thousands of photomultipliers within the telescope amplify the feeble Cherenkov light and turn it into an electrical signal. Astronomers can then follow the path of the muon and its shower across the volume of the telescope, based on which detectors lit up where and when, to reconstruct the direction and energy of the neutrino.

Top three neutrino telescopes

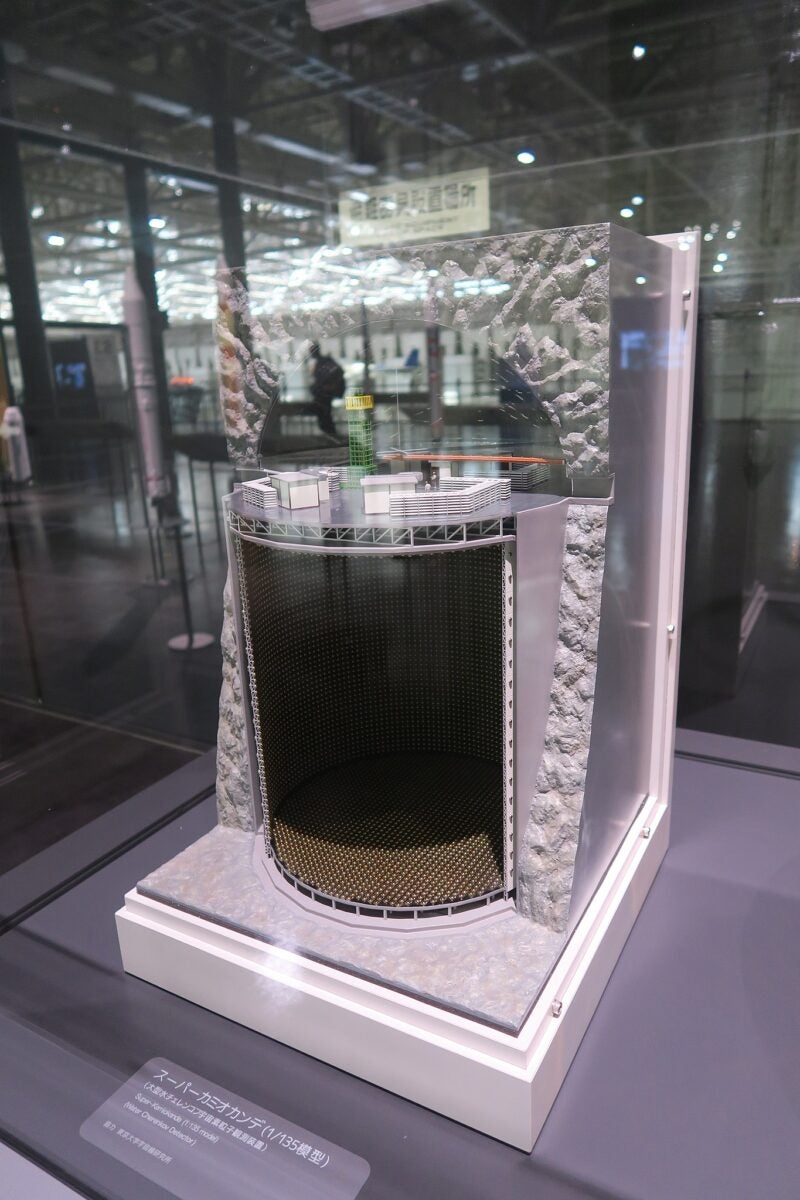

Today, the most famous neutrino detector is likely Super-Kamiokande in Japan, which began operation in 1996. This detector consists of a stainless-steel tank containing 50,000 tons of ultra-pure water buried 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) beneath Mount Ikeno.

The IceCube Neutrino Observatory, designed by physicists at the University of Wisconsin, turns to a natural source for a detector: the Antarctic ice sheet. IceCube, which began operation in 2010, is located at the Amundson-Scott research station at the geographic south pole. There, strings of thousands of detectors are sunk deep within the super-clear ice, giving it an effective detection volume of more than a 0.24 cubic mile (1 cubic kilometer).

Similar to IceCube, the European Cubic Kilometer Neutrino Telescope (KM3NeT) lies beneath not ice but water — the Mediterranean Sea — with thousands of detectors off the coasts of France and Italy, with another array in Greece under development. Construction is ongoing with about 10 percent of the detector currently functioning.

Related: Underwater detector spots the most energetic neutrino yet

Neutrino detections

Even with these gargantuan telescopes, neutrino sightings are incredibly rare.

In 1987, astronomers witnessed a supernova explosion in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way. But just before the flash of light appeared, detectors around the world caught a burst of neutrinos. The neutrinos arrived first because they were able to pass easily through the cloud of debris surrounding the dying star, while the light had to take its time filtering its way through the thick gas.

Despite trillions of neutrinos passing through Earth due to that single event, three neutrino observatories operating at the time captured only a grand total of 25 neutrinos. But that was enough to provide valuable insights into the nature of those powerful explosions.

Today, we have better statistics. Every day, IceCube detects hundreds of neutrinos, with the high-energy ones linked to star-forming regions, accretion disks around black holes, stellar mergers, and more.

Related: IceCube creates first image of Milky Way in neutrinos

The current record-holding neutrino comes from KM3NeT. On Feb. 13, 2023, the detector witnessed a single neutrino slam into the Mediterranean waters with an energy of around 220 peta-electronvolts. That’s 16,000 times more energetic than the particles in our most powerful colliders. The origin of that neutrino remains a mystery.

Neutrino observatories may stretch the very definition of the word “telescope,” but they give us a powerful window into some of the most extreme events in the cosmos.