In fact, every large galaxy in the sky came from an assemblage of small galaxies — and sometimes even from two like-size galaxies. The basic building blocks of the smallest galaxies are globular clusters, groups of stars sharing a gravitational influence. Once they attract each other, several globular clusters begin to form a dwarf galaxy. And it snowballs from there.

Astronomy magazine has teamed up with Emmy Award-winning artist Jon Lomberg to offer Galactic Tidal Star Streams. This poster is the first and only artwork showing galactic tidal star streams, which occur as larger galaxies rip stars away from smaller ones and consume them. You can get this 16” x 20” print at MyScienceShop.com today!

“That thing will merge with another similarly sized thing to create a slightly larger galaxy, over and over and over,” says Amanda J. Moffett, a postdoctoral researcher at Vanderbilt University who studies galaxy evolution.

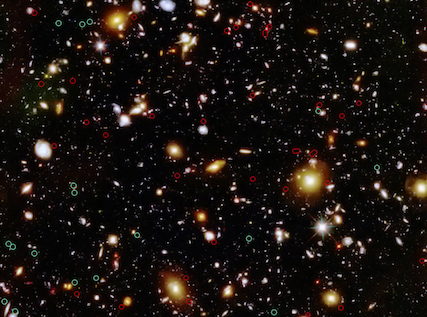

Today’s galaxies are the products of billions of years of mergers, some quieter than others. Astronomers are able to group most nearby galaxies into the three main classifications: elliptical, spiral, and irregular. But further back in time, almost all were irregular. These galaxies, the ones at high redshift (more distant and moving away from us faster), take on strange, unfamiliar forms.

“At high redshift, we do see galaxies that are just a spheroid-looking component; all we really see is a simple ball of stars,” Moffett says. It’s those simple balls of stars that got the ball rolling into the galaxies we see today.

The Milky Way’s recent merger history has been quiet, Moffett says. But like all galaxies, it’s a product of multiple building blocks, and it’s still picking on some of its neighbors, dragging them toward it in an inevitable dance between satellite dwarf galaxies and their larger host galaxies.

For instance, the Milky Way is bullying two neighbors, the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, irregular galaxies easily seen from the Southern Hemisphere. The same thing is happening to both: The Milky Way is drawing in filaments of gas, slowly siphoning matter off. This happens as the two satellite galaxies are also pushing and pulling at each other.

“They’re interacting with each other, but then our galaxy is very clearly bringing the pair in as well with these streams of gas that are coming out of the system,” says Mary Putman, a Columbia University astronomy professor. Some satellite galaxies end up in a sort of death spiral with the larger galaxy. “They will eventually fall in due to dynamical friction and the large gravitational pull of our galaxy,” she says. “The timescales can be very, very long though, depending on their orbit.”

Two things happen when a dwarf galaxy gets tugged on by a larger galaxy. Dust is pulled out in a process known as ram pressure stripping, leaving a “naked” dwarf. Gravity also pulls the stars inward, and the dwarf begins to look like the Sagittarius Stream, a group of stars ripped from the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy and currently spiraling into the Milky Way.

At one point, we may have even merged with a big galaxy. “The last possibility for a major merger was quite a long time ago, when our thick disk formed,” Putman says.

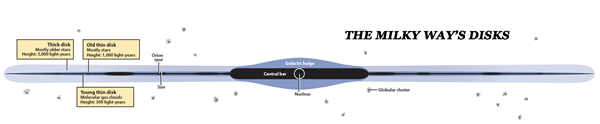

The Milky Way has two disks of stars moving at different velocities. The thin disk is from the beginning of the galaxy, while the thick disk was bulked up during a merger — though Putman says it’s not yet well understood what the merging galaxy was like.

So what happens inside a bigger merger? While the two groups of stars and dust may have a lot of mass, there’s also a lot of space between objects in a galaxy. This means that while the effects of a merger can be extreme for the structure of the galaxies themselves, they don’t necessarily greatly affect the stars within.

“Most of the time in these mergers, stars move right between each other and really only interact gravitationally,” Moffett says. “Your orbits might get disrupted a little bit because of extra gravitational pull from other things that are around them, but they don’t typically collide.”

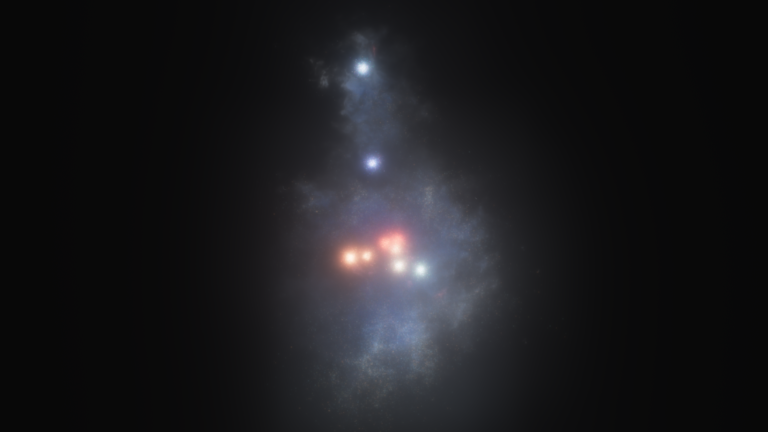

But things do get weird — really weird. Just look at the Antennae Galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), which are in the process of becoming one. Trails of stars are thrown across thousands of light-years as they move inward, and the galactic cores are moving closer together. Eventually the two objects will settle into a more regular shape, but that’s not today.

In typical mergers between two large galaxies, they first slingshot past each other. This disrupts the dust of the galaxies. After the near miss, they move in close and then move apart once again, but that close pass is enough to start to destabilize their structures. The galaxies then begin the official merger, often appearing as a cloud of stars and dust that settles over time, their former central regions blending and creating a new, more powerful center of gravity.

Past encounters

Putman says the Andromeda Galaxy (M31) may have already had one merger in the past. The galaxy has two supermassive black holes (SMBHs) at its center, something that would be unusual if not for mergers. But having two supermassive black holes merge? That’s quite a different subject.

“What simulations in computers tell, or have been telling for a while, is that you can only bring two [supermassive] black holes to a certain distance and then they’ll stall,” says Salvatore Vitale, an MIT professor who works on the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) project. Strangely, if they did merge, the gravitational waves produced would be far, far outside of LIGO’s detectability. We’d be more likely to see the fireworks show from infalling gas.

But standing between us and a SMBH merger is the Final Parsec Problem, that physical barrier that holds two supermassive black holes from merging, instead locking into an orbit lasting billions upon billions of years.

Once galaxies settle in, there aren’t many ways of teasing out their merger history without examining them in detail. That’s hard with them being so far off. But every large galaxy has come together through a merger — and other, bigger mergers may be just over the horizon.

Editor’s note: The quote from Salvatore Vitale has been adjusted for clarification. An earlier version of the quote did not specify the two black holes involved were supermassive.