Do astronomers have any estimates of when Saturn’s rings will disappear?

Doug Kaupa

Council Bluffs, Iowa

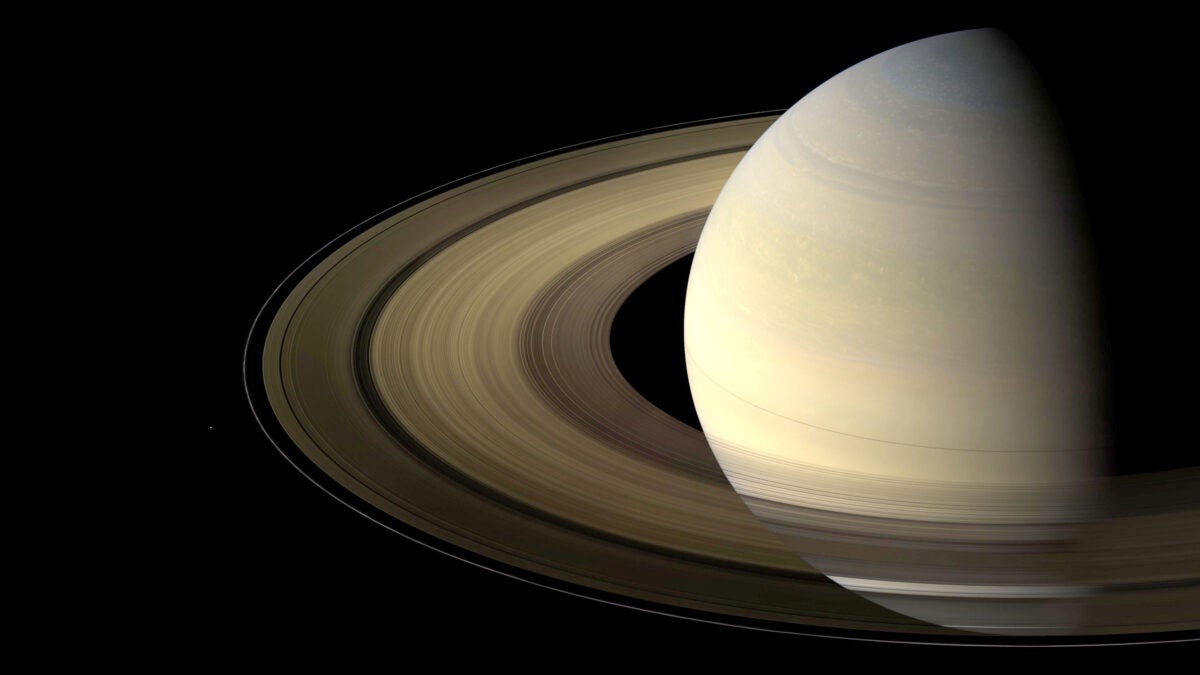

All four of the solar system’s giant planets have ring systems. The rings of Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune are dark, sparse belts or ringlets. Only Saturn’s massive main rings are dense and bright, made of almost pure water-ice particles ranging in size from dust and pebbles to boulders. You can visualize Saturn’s rings as an enormous swarm of snowballs and snowman-sized pieces orbiting the planet.

Most planetary scientists once thought Saturn’s rings were as old as Saturn itself: 4.5 billion years. But the Cassini spacecraft, which orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017, accumulated evidence that the rings are relatively recent. If early dinosaurs were smart enough to build telescopes, they might not have seen rings around Saturn at all. Cassini’s findings also suggest the rings are short-lived, with a lifetime of hundreds of millions of years.

Astronomers arrived at these estimates based on several measurements.

Cassini ended its mission in 2017 with its Grand Finale, 22 plunging orbits in which the craft swooped between Saturn and its innermost ring, the D ring. This allowed Cassini to determine the rings’ mass by comparing the gravitational pull on the spacecraft during its close-in orbits to the pull it experienced when orbiting farther out, exterior to the rings. The mass of the ring system is comparable to but less than that of Saturn’s innermost icy moon Mimas.

At the same time, Cassini observed material flowing from the rings into Saturn at many tons per second. Combining this mass loss with the rings’ current mass suggests a remaining ring lifetime (or mass-loss age) of only a few hundred million years.

Cassini also determined the rings’ so-called pollution age. During its 13 years orbiting Saturn, Cassini’s onboard dust detector measured the impact rate of interplanetary micrometeoroids. These dust particles are pulled in by Saturn’s gravity and strike the ring particles. Interplanetary dust is mostly dark, non-icy stuff. Over time then, the rings should grow polluted. How fast they darken depends on the dust influx rate and the ring mass. Based on Cassini’s measurements, researchers determined that this influx would darken the rings to the current observed level in at most a few hundred million years. This independently determined pollution age agrees with the mass-loss age.

The mass deposited in the rings by these meteoroids also reduces the orbital angular momentum of the ring particles and causes them to drift inward. Such dust impacts can additionally exert a negative torque. Furthermore, micrometeoroids hit at tens of miles per second. This is like setting off a firecracker in a snowball. Debris gets thrown around the rings, and some can even rain down directly onto Saturn. The combination of all these dynamical effects produces inflow at rates comparable to the inflow rate Cassini observed.

So, the conclusion is that Saturn’s rings are not more than a few hundred million years old and will not exist as bright, dense rings for more than another few hundred million years. What will they become? They may persist for billions of years, looking more like the sparse, dark ring systems of the other giant planets.

Richard H. Durisen and Paul R. Estrada

Professor Emeritus of Astronomy, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana,

and Research Scientist, NASA Ames Research Center, Mountain View, California