In 2021, Alyssa Collins was awarded a yearlong Octavia E. Butler Fellowship from The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California.

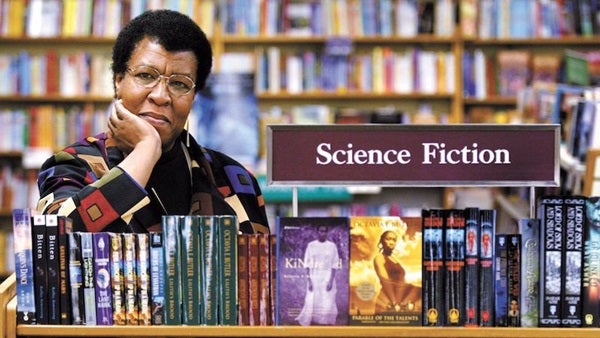

Butler, whose papers are held at the Huntington, was the first science fiction writer to be awarded a MacArthur Genius Grant. A pioneering writer in a genre long dominated by white men, her work explored power structures, shifting definitions of humanity and alternative societies.

In an interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, Collins explains how Butler’s boundless curiosity inspired the author’s work, and how Butler’s experiences as a Black woman drew her to “humans who must deal with the edges or ends of humanity.”

Butler, who died in 2006, would have turned 75 years old on June 22, 2022.

How did you become interested in Octavia E. Butler?

I first read Butler’s work in a graduate course on feminist literature and theory. We read “Parable of the Sower,” an apocalyptic novel published in 1993 but set in 21st-century America. I was really intrigued by the prescient nature of the novel. But I wanted to know if she had anything weirder on her backlist.

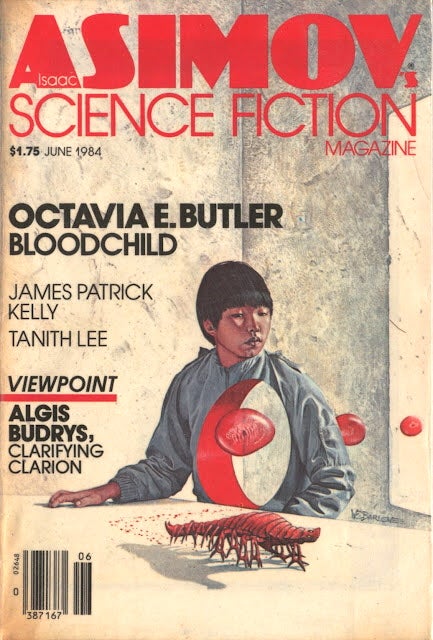

I managed to get my hands on “Bloodchild,” an award-winning short story that came out in 1984 about aliens and male pregnancy. After reading that story, I was pretty much hooked.

Can you give us an idea of the scope of this collection, in terms of its volume and value, and how much of it you were able to read during your fellowship?

The Octavia E. Butler collection consists of manuscripts, correspondence, photos, research materials and ephemera. It’s housed in 386 boxes, one volume, two binders and 18 broadside folders.

As you can imagine, it’s a great deal of collected material – so much, that when I began my fellowship, I was told by the curator who processed the collection that I wouldn’t be able to see everything.

I’ve spent most of my time working through Butler’s research materials, her correspondence with authors and her drafting materials, including her notecards and notebooks. I’ve found that the content in these notebooks has been an invaluable window into Butler’s scientific thinking.

What was one of the most surprising things you learned about Butler from the collection?

Even given what I knew about Butler as a celebrated writer and scholar, every day I spent in her archive only increased the amount of esteem I hold for her. I was continually surprised by not only the breadth of her interests and the depth of her knowledge, but also in the way she was able to synthesize seemingly disparate topics.

Her interest in subjects such as slime-molds, cancer and biotechnology come through in her stories in ways that readers might not expect. Take Butler’s interest in symbiogenesis, an evolutionary theory based on cooperation rather than Darwinian competition. In “Bloodchild,” in which humans help insectlike aliens procreate, readers can see Butler plumbing this theory by imagining different ways humans can interact and evolve with other species.

Your project is called “Cellular Blackness: Octavia E. Butler’s Posthuman Ontologies.” What is posthumanism and how does it relate to Butler’s work?

My book project was born out of a project I started in graduate school that was interested in how Black speculative writers in the 20th century imagined and interacted with a field of thought called posthumanism. Scholars of posthumanism think about the limits of what makes us human – or how we define humanity – and if there are couplings with technology that might make us posthuman now or in the future.

I wanted to know how Black writers were engaging with the idea or concept of posthumanism when Blackness had historically been imagined as inhuman – in, for example, justifications for the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Jim Crow segregation and ongoing state violence against Black people.

What interested me about Butler’s work is that her writing consistently represents humans who must deal with the edges or ends of humanity. She also places important decisions about humanity in the hands of Black women characters – individuals who have been dehumanized or erased. My book project looks at how Butler imagines these decisive moments and how she sees humanity defined and realized in her novels.

What about this idea of “cellular Blackness”?

It seems that Butler’s own speculative investigation of humanity doesn’t happen on the scale of bodies, but instead on the scale of cells.

In Butler’s 1987 novel “Dawn,” a Black woman named Lilith considers helping a group of aliens who are interested in interbreeding with humans in a way that would effectively “end” the human race. Lilith, who has a history of cancer in her family and a tumor that the aliens removed, has what the aliens call a “talent for cancer.” They’re interested in the possibilities that could come from regulating cellular growth.

It turns out that Butler was interested in the story of Henrietta Lacks, a 31-year-old Black cancer patient whose tumor cells were collected without her knowledge at Johns Hopkins in 1951. Unlike the other samples that had been collected at the lab over the years, Lacks’ rapidly reproduced and stayed alive even after Lacks died that same year. To this day, her prolific cell line – called HeLa cells – are used around the world to study cancer cells and the effects of various treatment.

In her unpublished notes, Butler imagines what HeLa cells, with their unending replication, could offer outside of a person’s death. In works like “Dawn,” you can see Butler thinking about cellular replication as a concept that extends humanity, whether it’s symbiosis with other species or through human evolution.

The “Parable” books, which were written in the 1990s and set in the 2020s, have seen a resurgence in popularity in recent years. Butler’s vision of the near future in these works – with society on the brink due to looming environmental catastrophe, unchecked corporate greed and worsening economic inequality – seems prescient. Did your time in the collection give you any new insights on their enduring relevance?

At Butler makes clear, the problems of extreme climate change, income inequality, capitalistic exploitation, housing shortages, racial prejudice and the defunding of education aren’t new problems.

She read widely – newspapers, scientific textbooks, anthropological tomes, fiction, self-help books – and thought deeply about what she read. I think Butler simply took what she learned from these sources, which hinted at where things were heading, and imagined what a not-so-distant future would look like if nothing were fixed.

Well, as Butler shows us, these problems haven’t been fixed, and they’ve only worsened in the 30-plus years since she wrote the books.

The first “Parable” novel’s protagonist, Lauren, creates a belief system called “Earthseed.” It contains mottos of change – for example, “God is Change” and “All that you Change, Changes you” – and I think Butler hoped Earthseed might encourage people to change the world in some meaningful way. These books feel relevant because there are still a lot of people who are interested in pushing for, imagining and making change.

Laura Erskine contributed to this interview.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.